I persuade Anna to come to Rotterdam and look at the Bruegel.

Rotterdam. To recapitulate: a station, a street, a museum, the wind, and The Tower of Babel .

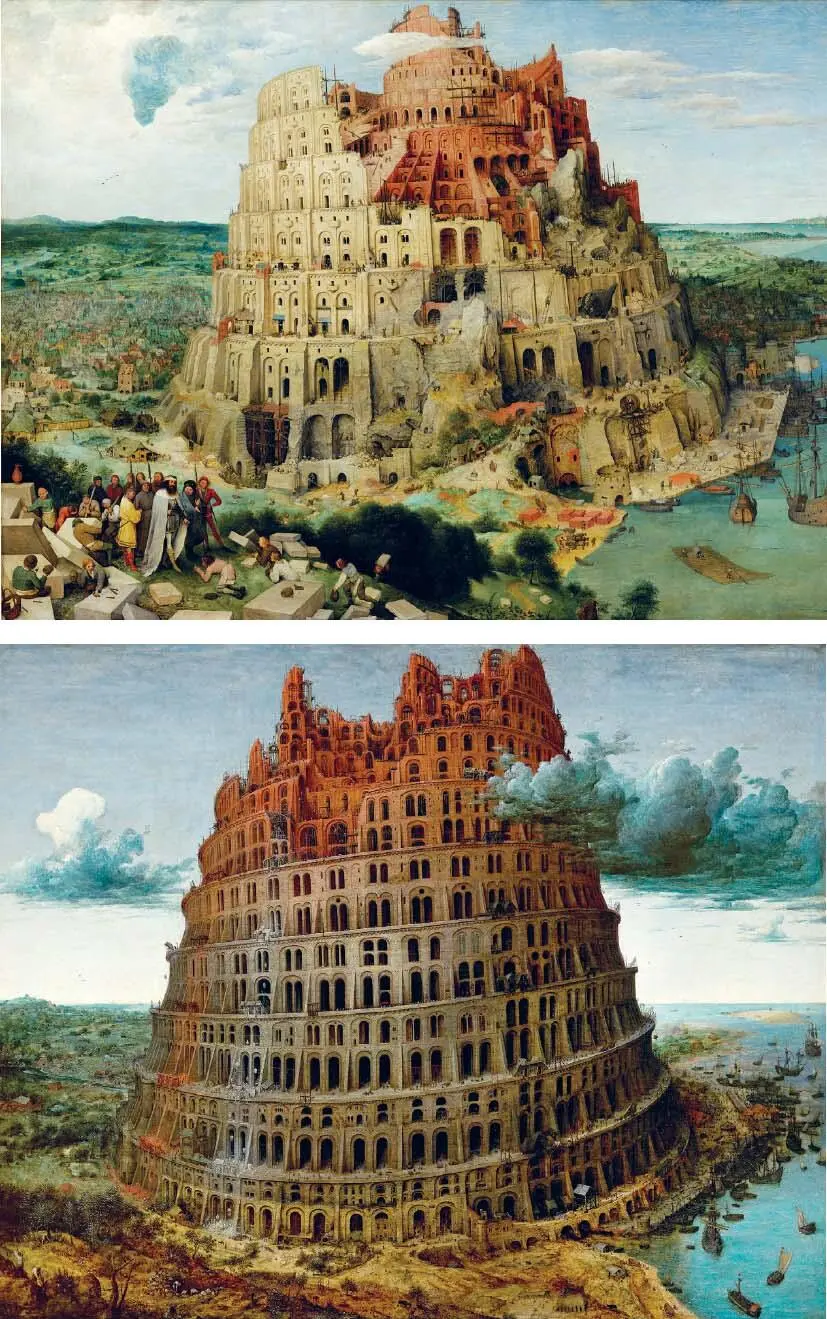

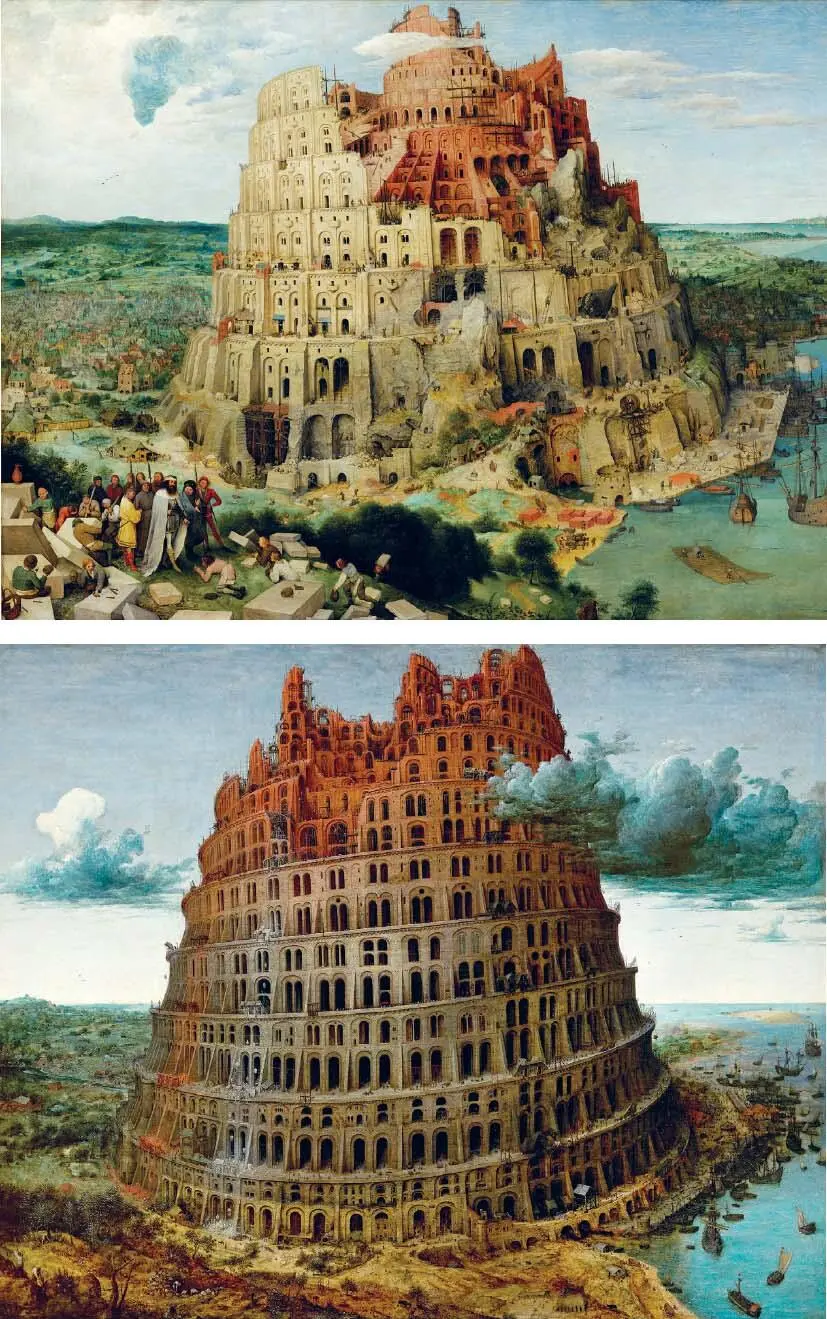

Museums are for the most part horizontal structures. I do not know many properly vertical museums. But the Rotterdam museum contains one of the great essays in verticality. It is the smaller of Bruegel’s two Babel panels – the other hangs in Vienna – but the larger of the two towers. The compositions are similar. The Vienna tower is built around a cankerous rock and in the foreground, receiving obeisance from his stonemasons, there is a king (Flavius Josephus ascribed the building of the tower to Nimrod); the ships are much larger than those in the Rotterdam panel, the horizon subtly higher; in Rotterdam we are higher, therefore, and see further.

Essays in verticality: The Tower of Babel – Vienna (top) and Rotterdam (bottom).

The rocky outcrop jutting from the Vienna tower is not the foundation but the metamorphosis of the built structure – there can have been no pre-existing plugs of rock on this flat plain. The weight of the tower has compressed and transformed its materials. It is subsiding on the shore side into marshy land.

The Rotterdam panel, on the other hand, is a pure geometry. Lessons have been learned. The only transmutation of materials here is into upthrusting energies. No wonder the builders’ jealous god got worried.

Both towers not only dominate their respective landscapes: they are the landscape. Everything of interest on the nondescript plains is subsumed into the towers, just as a great city – Antwerp, for instance, or Brussels – will suck economic energy from the land and the seas which surround it.

Bruegel was an inheritor of the Netherlandish tradition of the World Landscape – painters such as Herri met de Bles and Joachim Patinir had for a generation before Bruegel produced increasingly broad and schematic landscapes where great rivers and mountains and plunging precipitate views and cliffs and oceans beyond stood as much for a representation of the cosmos as for anything you might see in nature.

Landscape started to emerge from the background, took a sociological, topological, cartographical, thematic turn. It became not just a reflection of cosmic order but the whole theatre of man and his salvation, the teatrum mundi , the theatre of the world.

Bruegel introduced a note of difference, however. A naturalism. Simon Schama observes that, relative to the work of Patinir and met de Bles, the landscapes of the early seventeenth century had been ‘deprogrammed’. They had ceased to be grand schematics of the cosmos, or moral topographies, and were now ‘just’ trees, woods, streams. And this process of deprogramming begins with Bruegel.

In around 1552, Bruegel, a young painter newly emerged from his apprenticeship, travelled to Italy, most likely with fellow painter Maarten de Vos and the sculptor Jacob Jonghelinck. He travelled down through France (we know of a lost gouache View of Lyon ); proceeded over the Alps to Rome, where he stayed for two years; and then pressed on more briefly to Naples, Reggio Calabria, and in all likelihood Sicily.

Such a trip was not unusual for ambitious Northern painters, who were expected to educate themselves in the ruins of classical antiquity and the works of the Italian Renaissance masters. Bruegel most likely did precisely that but, perhaps at the instigation of the Antwerp printer Hieronymus Cock, he also documented his trip with reams of topological views: the Bay of Naples, Reggio Calabria, the Strait of Messina, Rome, the Alps. And on his return, it was with these views and a set of generic engravings – the so-called Large Landscapes , incorporating elements of his Alpine journey – that the young Bruegel established his reputation. ‘On his travels,’ wrote Van Mander, ‘he drew many views from life so that it is said that when he was in the Alps he swallowed all those mountains and rocks which, upon returning home, he spat out again on to canvases and panels.’

Bruegel had a precise eye. His work has been described as ‘ethnographic’, so fastidious is it with details of peasant life, and in the same way his World Landscapes never neglect shape of leaf or jizz of flying bird – a generic silhouette in the sky is, on closer inspection, a magpie or a cormorant; a foreground plant is not just an iris but an Iris germanica . The natural world adorns the schematic landscape, or the schematic landscape polarizes the naturalistic detail, in a way that Ruisdael or Hobbema, or Constable or Monet, would have understood. The real keeps impinging on the meaningfully arranged. And vice versa. We are caught in suspension between what God ordains and what Bruegel experiences. And the two are not necessarily aligned.

On his Italian journey, Bruegel must have seen and drawn, and, to judge from his versions of Babel, slightly obsessed over, the Colosseum. Both the Rotterdam tower and the Vienna tower are colosseums telescoping upward to infinity. Both are set on the plain. There are some distant hills in the Vienna panel, none in the Rotterdam panel. To repeat, both towers are the landscape, translations of the cosmic landscape into urban form. These are stone cities pulled up from the earth in the manner of origami trees, birthing strange rocks, over-topping the clouds, bending the frame of the earth. Symbolic, but also detailed. Naturalistic.

The Rotterdam tower – the later of the two, by some five years – is both an architectural and a chromatic fantasy.

At the top, the endless intricacy of its internal form is revealed. The Gothic variation and repetition of its windows and arches makes of them not merely entrances but a sort of hyperbolic internal structure, as though the builders had lighted on some multidimensional or geodesic solution to the incalculable stone weight of the structure that had defeated them in the Vienna panel; this fresh tower will go up and up supporting its own weight on tensile Gothic arches and windows.

Pollen of the mason’s art: The Tower of Babel (Rotterdam), detail.

There is no king here, no central intelligence and motive force. The builders of this monstrous beautiful thing scurry over its exterior and interior like the manifestation of an algorithm, working their twig-like cranes and filigree hoists, leaving deposits on the pinkish sandstone of white and red from where the marble dust and brick dust are shaken like chalks, pollen of the mason’s art.

*

At the base of both towers are culverts or sally ports where a boat might drift inside, sail right into the heart of the endlessly ramifying structure. You might load your ship with barrels of gunpowder and seek out the keystone, the arch or spar whose destruction would bring the whole of this tyranny crashing down. Every project has its point of weakness. A niggle, a suspicion, a discord. If there were not, there would be no need for a project. Straight life would suffice. The project is an attempt to reconcile irreconcilables, to square the circle. Something must be fudged in the process.

Freedoms, for instance. Manfred Sellink, cataloguer of Bruegel, finds the Rotterdam tower more menacing than the Vienna; the equally eminent Larry Silver regards it as an index of the productive capability of a free people (the Netherlanders) contrasted with the crooked construction of a subjugated slave race (the Spanish).

I do not know whether the tower is menacing or not. It is certainly fascinating. Did Bruegel have the ways of tyranny on his mind? It seems obvious to us – his Netherlands were part of the Habsburg Empire, effectively under Spanish rule. In his lifetime its people would start to resist, and, just months before his death, rebel.

Читать дальше