The first Norman king’s successor, his ruddy-faced son William Rufus, was killed in the forest in August 1100, shot through the breast by a rogue arrow supposedly aimed at a stag by one of his companions (though assassination is not out of the question). William Rufus’s older brother Richard had also died some years previously in a hunting accident in his father’s preserve. And three months before, in May 1100, the king’s illegitimate nephew had likewise been slain hereabouts by another arrow gone awry. These two earlier incidents should perhaps have served as a warning to the country’s new ruler about the hazards, if not of the forest itself, then of his chosen pastime. But, even if the memory of how his relatives had met their end no longer weighed upon William II, various contemporary warnings and omens do appear to have had an effect and led the king to postpone the departure of his ill-starred stag hunt. However, this was to delay his doom for just a few short hours.

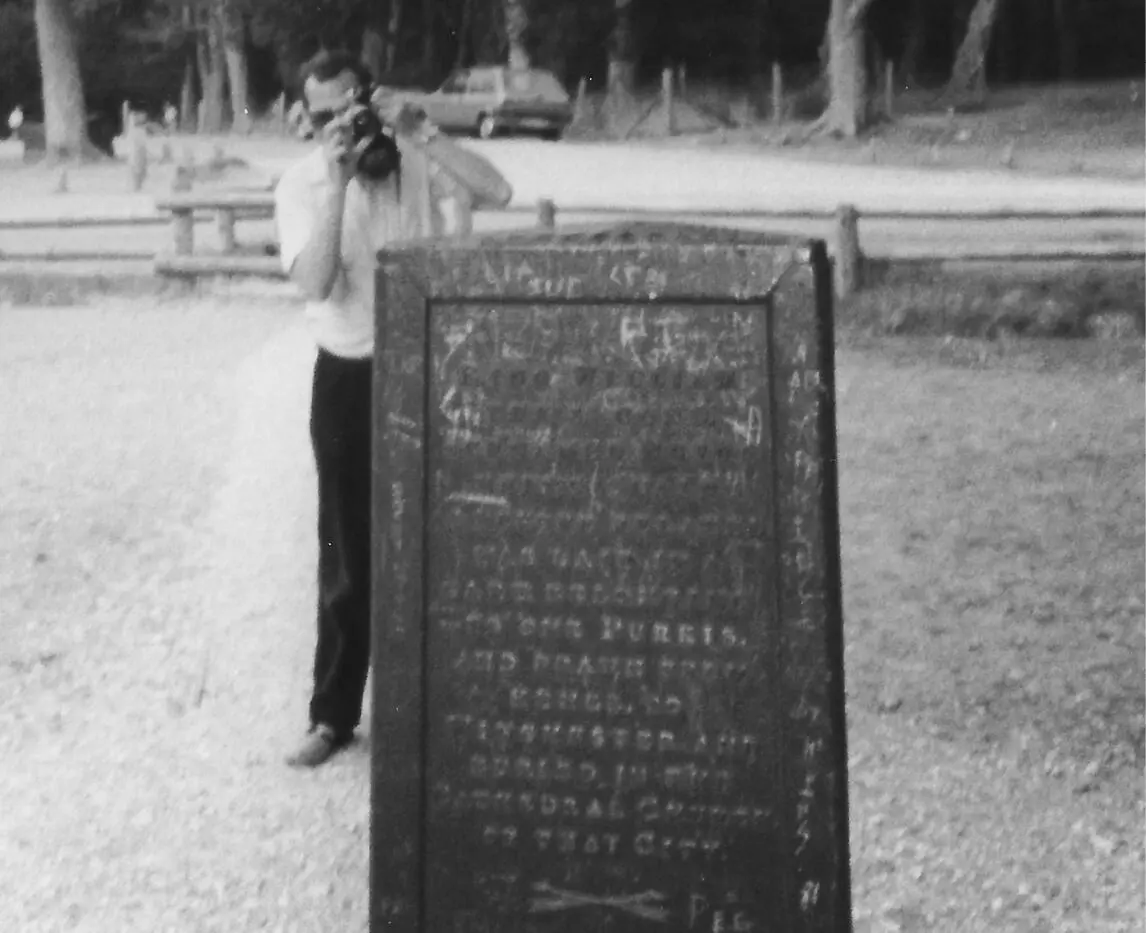

We visited the Rufus Stone, which marks the spot of the regicide, during that same sunburnt summer: the original stone, according to the 1841-erected replacement, was ‘much mutilated, and the inscriptions on each of its three sides defaced’. Among my box of old family photos and slides I can find only a solitary picture of the marker post – an image of my father engaged in the act of capturing the monument on film; the photo possesses a grainy, otherworldly hue that now would have to be digitally fabricated by some Instagram or iPhone filter. In more recent years the unobtrusive turnoff on the A31 has beckoned me to the place every time I’ve passed it on my way to see my brother at his nearby Dorset home.

Today is different – I’m heading in the opposite direction and there is no prospect of the two of us meeting later and searching the skies for twist-tailed honey buzzards. Before, though, I have often given in and broken my long journey, turning across the busy dual carriageway to absorb the atmosphere of the forest around the monument, wondering if this was also where Dad and Chris happened upon their infamous serpent. If so, perhaps another less grand marker would now be appropriate?

That the spot where an event so memorable might not hereafter be forgotten – close to here a man and his son watched a grass snake devour a fully grown frog.

Philip Hoare’s book England’s Lost Eden relates the strange events and portents surrounding the death of William Rufus in wonderful detail, before going on to catalogue the hypnotic attraction that the mysterious, superstition-filled Arcadia offered towards the end of the Victorian age to those who came here seeking a higher plane. He tells of how the forest became host to Mary Ann Girling, a farm labourer’s daughter from Suffolk who claimed to be the stigmata-scarred Messiah, but ended up encamped in increasing squalor with her rag-tag band of followers outside the village of Hordle; their Rapture never did arrive, just starvation and disappointment and, for Mary Ann, the cancer of the womb that would kill her.

At the same time as Mary Ann’s New Forest Shakers were attracting day-tripping tourists to gawk at their sorry spectacle, an eccentric Spiritualist barrister, Andrew Peterson, channelled the ghost of Sir Christopher Wren at séances and built a monument to the lure of the esoteric at nearby Sway. Today, as I walk along the narrow lane at its base, the 218ft folly – believed still to be the tallest non-reinforced concrete structure in the world – seems somewhat forlorn, squeezed in among houses and bungalows and crying out for a grander backdrop. Glimpsed, however, from a distance, jutting above the breeze-blown trees, its incantatory effect remains undiminished.

A mile and a half south-east of the Rufus Stone is Minstead. At the back of the village’s delightfully ramshackle, red-brick All Saints’ Church lies the grave of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, another who found comfort in the forest, drawn to Spiritualism after the death of his eldest son Kingsley, who was wounded at the Somme and died in 1918 from the resulting complications. The originator of Sherlock Holmes had famously been taken in by the fairies photographed by two girls, sixteen-year-old Elsie Wright and her nine-year-old cousin Frances Griffiths, at Cottingley near Bradford. The images came to Doyle’s attention via the Theosophical Society, and he broke the sensational story in a December 1920 article in The Strand magazine; the women finally confessed to the fakery more than sixty years later, long after Doyle had printed his full investigation of the pictures in his book The Coming of the Fairies . Doyle maintained that ‘there is enough already available to convince any reasonable man that the matter is not one which can be readily dismissed’, albeit adding that: ‘I do not myself contend that the proof is as overwhelming as in the case of spiritualistic phenomena.’

Glenn Hill/Contributor via Getty Images

By this late point in his life Doyle’s faith in Spiritualism was seemingly without scepticism. He was by no means alone in his beliefs, as the unprecedented slaughter of European youth that had taken place during the First World War had led to an upsurge of interest from those of the bereaved who wished to attempt communication with their dead loved ones. In 1927 Doyle published Pheneas Speaks , a catalogue of comforting messages received from the other realm at private family séances by his second wife Jean, who acted as medium. Pheneas was their third-century BC Mesopotamian spirit guide, who directed first Jean’s automatic writing (referred to as ‘inspired writing’ by Doyle) and later ‘semi-trance inspirational talking’. Many of these séances were held at their mock-Tudor New Forest retreat, Bignell House, a couple of miles east of the Rufus Stone; Pheneas even requested a room of his own in the cottage, decorated in mauve, which would psychically lend itself to ‘clearer vibrations’. The family conferred with departed relatives including their late, war-wounded son Kingsley, and Doyle’s brother-in-law – the novelist E. W. Hornung (husband of Doyle’s sister Connie), author of the Raffles ‘gentleman thief’ stories and a renowned non-believer in Spiritualism while alive. John Thadeus Delane, a former editor of The Times who had died in 1879 – a person and name, according to Doyle, apparently ‘quite unknown to my wife’ – also appeared in the ether for a chat. When asked whether he still edited a paper in the next world, Delane replied: ‘There is no need here. We know everything. It is like wireless in the air, and all so much bigger and larger and so splendid. It is great, this life.’

Later, at the same June 1922 séance, Doyle’s thirteen-year-old son Denis, ‘a great lover of snakes’, asked Kingsley: ‘Where are the snakes with you?’ To which his ghost brother replied: ‘In their own place, old chap. We are so proud of you, Denis, and the way you are developing in every way.’ Reading these transcripts now it’s difficult to imagine how the man responsible for the creation of the arch-rationalist Sherlock Holmes could accept these banal messages so unquestioningly as solid evidence of an afterlife, and not as the understandable attempts (either consciously or subconsciously) of his wife – who had also lost her brother during the Great War – to bring comfort to a grieving old man and his family.

Читать дальше