I discovered it when I heard a gang banging on our gate one night demanding to see Victor about some unpaid debt and threatening to do him serious damage if he didn’t pay up. I dragged Titus to the gate and he barked ferociously, straining on the leash. The men cleared off pretty sharply. They need not have. What they didn’t realise was that he was not threatening them: he was straining to run away.

A few months later, when Titus and I were returning from our regular morning run around Zoo Lake I saw some black men standing at our gate. So did Titus. I tried to grab his collar but too late. He was running hell for leather in the opposite direction. Not for nothing are ridgebacks known as lion dogs. When their ancestors were used for hunting lions they were capable of running all day and all night – which is exactly what Titus did. We searched everywhere, put up ‘missing dog’ posters, even contacted the police (fat chance there) but after two days we’d begun to give up. Then the phone rang. It was a very elderly lady.

‘Have you got a dog called Titus?’

‘Well,’ I said, ‘we used to have but he’s run away.’

‘He’s with me and his feet are all torn and bloody. You must come and get him.’ Titus had run clear across the city and Joburg is a very big city. Thank heaven we’d put a disc on his collar with his name and our phone number.

My wife and I also found it difficult to live with the constant low-level hostility we met because I worked for the hated BBC – hated, at least, by Afrikaner officialdom. We represented the enemy. The British ambassador expressed it well when I asked him just after we’d arrived how we could expect to be treated.

‘Well put it this way,’ he told me, ‘as the representative of Her Majesty’s Government I tend to find myself going everywhere with my fists half raised.’ For the most part, though, they left me alone to get on with my job. There was the occasional visit from policemen calling at my home with spurious claims that I had been seen driving dangerously or committing some other low-level offence, but it was pretty half-hearted stuff – presumably just to remind me that they knew who I was and where I lived. Potentially more serious was when the South African government demanded that the BBC recall me to London. They ordered their ambassador to make representations to the head of news at the BBC, Alan Protheroe, and a meeting was duly arranged.

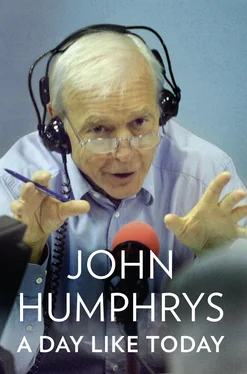

Alan listened politely. The case was, on one level, unanswerable. Mr Humphrys, said His Excellency, was opposed to the South African government and its policy of apartheid. Difficult to argue with that, but was I getting it wrong? As Alan pointed out, the BBC would need hard evidence that I was failing to report accurately what was actually happening in South Africa before it would consider replacing me.

‘Ha!’ said the ambassador (as reported to me later by Alan). ‘I shall give you one very concrete example of his inaccuracies. When he reported on the rugby match between the Lions and the Springboks in Durban just the other day he said the first try was scored by Grobelaar and it wasn’t: it was scored by Geldenhuys. The man cannot be trusted!’

That was fair enough as far as it went – sport has never been my strong point – but my boss took the view that it did not necessarily prove I was unfit for the job of South Africa correspondent, all other things considered. And that was the end of that. A faintly ridiculous encounter, but with an important principle underlying it.

The ambassador was dead right when he said I had not been reporting from his country with the impartiality that the BBC demands from its journalists. Normally that might indeed be a sackable offence. Frederick Forsyth was sacked by the BBC in the late 1960s (or, if you prefer, allowed to resign) because he was sympathetic to the Biafrans when he was reporting on the civil war there. He had the last laugh. He tried his hand at writing a novel and the rest, as they say, is history. Day of the Jackal became a massive international bestseller and a blockbuster film, and there were many more where that came from.

But the principle stands. BBC correspondents are reporters, not commentators. We report the views of others, not our own. The BBC is, above all else, impartial. And yet … there is one exception that overrides even that iron law. It was pronounced by the man whose shadow has hung over the BBC since he became its first director general in 1927: John Reith. The BBC, he said, is not required to be impartial as between good and evil.

In my view and – rather more importantly – in the view of the BBC, apartheid was an evil doctrine. It’s true that I did not use my access to the BBC airwaves to denounce the National Party government of South Africa and demand its overthrow, but neither did I try to pretend that the way it treated the vast majority of South Africans was anything other than repugnant. Not that it was easy to have a sensible argument about it with those Afrikaners – and there were many of them – who believed as a matter of faith that they were superior to the ‘kaffirs’. After all, they had God on their side. Their defence rested on the Bible. They liked to quote from the New Testament: ‘God made all nations to inhabit the whole earth, and He allotted the time of their existence and the boundaries of the places where they would live.’

See? Apartheid means ‘apartness’ and all they were doing was enforcing laws that meant blacks lived apart from white. And, please note, God also allotted the boundaries of the places where they should live. How very fortunate in the case of the white people in Johannesburg that they should be allotted the rich, luxurious suburbs while those with a black or coloured skin were allotted the stinking slums. But, as God would no doubt point out, it wasn’t HIS fault that white people would turn out to be so much better at accumulating wealth than black people. Which would also, presumably, explain why the whites should have the richest land in South Africa including (naturally) the gold mines, while the blacks should be banished to their ‘homelands’ – even if they’d never set foot in the godforsaken places.

To my enormous surprise I got the chance to challenge the country’s president about all that in a television interview which I asked for but never, for a second, believed I would get. It was clearly a sign that, for all its arrogance, the government knew it had to start persuading the rest of the world that apartheid was just and essential for the country to survive let alone thrive. The president was P. W. Botha, popularly known as ‘Die Groot Krokodil’ (The Big Crocodile). He had earned the nickname: he had a thick skin, the sharpest of teeth and was totally ruthless. I tried suggesting to him that simple justice and humanity demanded all people should be treated the same, whatever the colour of their skin. Here’s his reply: ‘Simple justice suggests that you must allow a black man with his family to live a healthy, decent life. And you must provide work, where possible, for him, and not allow him to squat on your doorstep … and then, in the name of Christianity, say you’ve done your duty towards him.’

In one twenty-second answer Botha had used the three phrases that summed up the apartheid philosophy: ‘allow a black man’; ‘in the name of Christianity’; ‘you’ve done your duty’.

There was not a scintilla of doubt in the minds of men like Botha that they were the master race and black people were a subspecies. Wasn’t he worried that they might have had enough of being subjugated by their white masters? Wasn’t some form of revolution inevitable?

‘People have said so over a period of 300 years,’ he told me. ‘And, today, South Africa is one of the most peaceful countries in the world to live in.’

Читать дальше