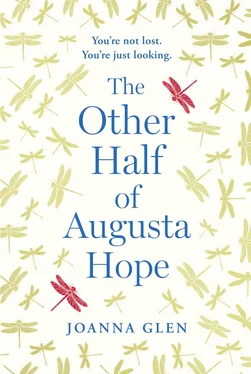

I was so happy that Julia got the Poet of the Week certificate, and I loved the way her little nose wrinkled like a rabbit when she read it, but I knew that this was not a good poem. Either the teacher had no idea about poetry or she had some other motive like balancing out the awards.

My mother and father laughed for some time together after Julia read the poem, which made me think they must be losing their minds. Even if you liked the rhymes, the poem was really not that funny.

‘I do get chilly in winter,’ laughed my mother, wiping her eyes, ‘and I am a bit silly in summer.’

Summer was coming, and my father would close the shop on 30 or 31 July (Julia’s birthday) for two weeks because so many people went away, and because my mother required that we too took a fortnight’s holiday.

My mother spent fifty weeks of the year planning our two-week holiday, which would be the only one my father was prepared to take because he never liked anyone else to run the shop, the way some mothers won’t pass their babies around. He had a sign in the window showing the whole calendar year. OPEN, it said in luminous ruled capital letters, with a single spindly pencil line through his holiday fortnight.

‘Six months until we go away,’ my mother would say.

‘Five’

‘Four’

‘Three’

‘Two’

‘One’

When we left for our holiday, my father would leave lights on timer switches around the house, mimicking our family routines, and he would go around checking them about five times before we left, and then one for luck. I told him that I’d never seen any burglars lurking about in Willow Crescent, and he said that they didn’t carry swag bags and wear striped T-shirts – burglars could be anyone, even people we knew and liked, even neighbours in Willow Crescent.

‘Even Barbara Cook?’ I said.

‘Obviously not Barbara Cook,’ he said.

‘You’re the Neighbourhood Watch man,’ I said. ‘Shouldn’t you have found out if any of our neighbours are burglars?’

‘Don’t worry your father when he’s so busy,’ said my mother, with her holiday glow, hoping my insolence wouldn’t make my father’s fingers start shaking, as it sometimes did, particularly on the day we left for our holiday, when he was taut with tension.

My mother started her trips to the travel agent in the autumn. She kept an eye on the newsagent board. She scoured the Sunday papers. She also used the school magazine where people advertised holiday homes and caravans.

Julia’s poem ended up being published in the school magazine. My mother cut it out and framed it, and my father nailed it to the hall wall. Julia put a chewy Werther’s toffee under my pillow with a note saying, ‘You are the real poet in the family.’

I chewed it with great humility as Julia said (not incorrectly), ‘My poem is actually quite bad.’

I wanted my mouth to make the words, ‘No it isn’t.’ But my mouth didn’t seem able to make those words, and, if it had, Julia would have known it was a total fib.

That’s the thing with being a twin, and maybe it’s the same with all brothers and sisters. You know the outside of each other, the body you bath with every night of your life, until you become too big to fit in together. Then one of you sits on the toilet lid and chats to the other in the bath until you run some more hot water and swap around.

You know the little splodge of birthmark on Julia’s right upper arm and the dark freckle on her left ring finger that helps her tell her right from her left, and you know her inside too just the same. You feel her tears before they fall – and you want to stop them, you so want to stop them, though you can’t, that’s the truth of it. You hear her laugh before it comes, and hearing her laugh makes you laugh too. Her lovely bright laugh.

In this way, your twin is your home.

Or mine was, anyway.

Far more than my home was ever my home.

What a word it is – home – a million meanings packed up in a giant handkerchief and hanging from a pole which we carry across our shoulder.

‘Didn’t you write a poem, Augusta?’ said my mother.

I nodded.

‘You must show me it,’ she said.

‘Don’t worry,’ I said.

‘I will worry,’ said my mother, which meant I had to go and get my English exercise book although I really didn’t want to.

‘Here it is,’ I said. ‘Miss Rae didn’t especially like it.’

‘I’m sure she did,’ said my mother, who obviously couldn’t be sure she did, especially as I could be absolutely sure she didn’t.

I opened the exercise book at the right page.

This is what my mother read:

‘My Mother’s Name’ by Augusta Hope

‘My mother’s name is Jilly

Which (apparently) is an affectionate

Shortened version of Jill

Although it is longer by y

Which makes me ask y

You don’t call a pill you love

Such as aspirin

(which removes head-aches)

A pilly

Or a hill you love

Such as Old John Brown’s

A hilly

Or a window sill you love

A window silly

But that would just be silly.’

Underneath, the teacher had written:

‘This is quite a strange poem, Augusta, and your rhyme pattern is not regular. Well done!’

My mother stared at the teacher’s comment.

Then she stared at the ruled grey line underneath. She was trying to read the indentations, and she was also trying to think what on earth she could say to me about my weird poem.

Underneath the teacher’s comment I had written:

‘ I didn’t actually want a regular rhyme pattern FYI ’ (which I’d discovered meant for your information ). Then I’d rubbed it out because I knew that, though it was true, it was also a bit rude – and precocious.

My mother went on straining her eyes to read underneath the rubbing out.

‘What did it say here?’ she said.

‘I can’t remember,’ I said.

‘It’s …’ said my mother, and she couldn’t think what to say.

‘It’s OK,’ I said. ‘You don’t have to like it. I know it’s a bit strange.’

‘Sometimes I wonder what is going on in that little head of yours,’ said my mother.

She did not frame my poem.

My mother was called Aurore, which means dawn.

And my motherland, still waiting for its dawn, is called Burundi.

Burundi carries its poetry in the hummingbirds drinking from the purple throats of flowers, the leaves glistening green after a night of rain; in the cichlid fish which flash like jewels deep beneath the surface of Lake Tanganyika, where crocodiles slumber like logs, still and deceptive, and hippos paddle downriver, in a line.

It carries its spirit in the dignified faces of all who are willing to forgive in the belief that Burundi will one day be beautiful again.

Dignified faces like my father’s.

I was his first son, and he prayed that by the time I was grown, we’d be living in peace.

‘You were born smiling,’ he told me. ‘And you were so perfect. Everything we’d ever dreamt of.’

‘So we called you Parfait,’ said my mother.

‘Parfait Nduwimana,’ said my father (which means I’m in God’s hands ).

‘You were the most beautiful baby,’ said my mother ‘with those little dimples in your cheeks.’

‘Why would dimples be beautiful?’ I said.

‘Just because!’ she answered, hopping over to me on her wiry legs, and stroking my left-hand dimple with her right hand.

She reminded me of a bird, my mother.

I loved to spot birds when I was out and about: the hoopoe, or the Malachite kingfisher, or my favourite, the Fischer’s lovebird – a little rainbow-feathered parrot which used to bathe in the stream up above our homestead.

Читать дальше