In (c), you need to force out ♠A and ♠K. To do this, sacrifice two of your sequential cards ♠Q, ♠J, ♠10, ♠9 (note that sequential cards between your hand and dummy’s are worth the same). Then you have promoted the two cards that remain into two force winners.

Useful tip

Don’t be overly concerned about losing the lead, particularly early in the play. You have to lose to win in bridge.

If you can exhaust your opponents of all of their cards in a suit, then your remaining cards, however small, will be promoted into ‘length’ winners. Assuming your opponents have no outstanding trumps, these remaining cards will be extra tricks.

must know

Length before strength – a general rule to follow in bridge: having more cards in a suit is often more important than a higher point count.

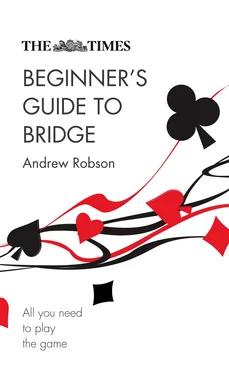

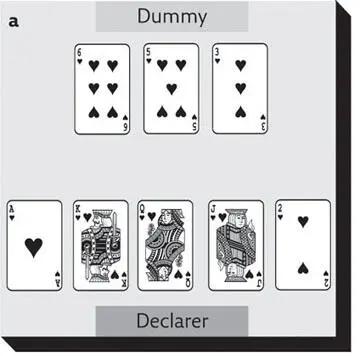

In (a), you have four ‘top’ tricks (tricks made consecutively, with high ranking cards), but it would be very unlucky if you didn’t also score ♥2. Your opponents hold five hearts between them. Unless they are all in one hand, they’ll all fall when you win ♥AKQJ. ♥2 will then be a fifth-round winner – by virtue of its length. This scenario depends on how the five missing hearts are split between the opposition. If they’re split 3-2 (most likely), or 4-1, you’ll achieve your extra trick by length. The only problem will be the much less likely 5-0 split.

In (b) start with ♥Q (or ♥2 to ♥Q), as it’s the highest card from the shorter length. Then lead ♥3 back to ♥J, and cash ♥A and ♥K. The six missing cards in the suit will go in these four rounds if the cards are split 3-3 or 4-2. Assuming they are (you’ll develop a habit of counting missing cards as they’re played), you can enjoy a length winner with ♥4. A 5-1 split, however, would prevent this. Fortunately, this is much less likely.

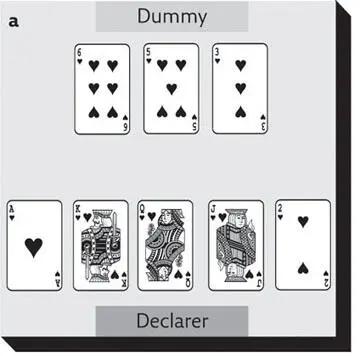

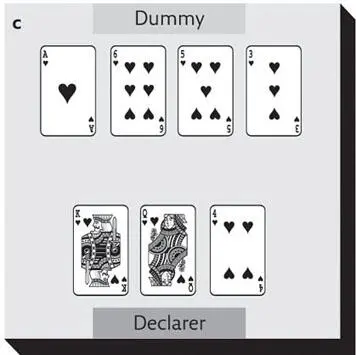

In (c), you have three top tricks but may also make a fourth-round length winner. There are six missing cards, held by the opposition. If the split is 3-3 (three cards in each opposition hand), you have the chance to enjoy a low-card length winner. Start with ♥K (or ♥3 to ♥K), then ♥Q, then ♥4 to ♥A. If all six missing hearts fall (i.e. both opponents follow suit all three times), then ♥6 will be a length winner. You’ll be less lucky if the suit splits 4-2 (or 5-1 or 6-0) as there’ll be an outstanding heart, which is bound to be higher than your ♥6.

must know

Your ability to generate length winners in a particular suit depends on how the missing cards in the suit are split between the opposition partners. If you are missing five cards from your own partnership you can expect them to be split 3-2 between the opposition, perhaps 4-1, or rarely (and less fortunately for you) 5-0.

Apart from length winners, the only way to make tricks with twos and threes is by trumping. Which suit is preferable here as trumps: ♠AKQ or ♣65432? The answer is clubs because ♠AKQ rate to score tricks whether or not they are trumps, whereas the only way the small clubs are likely to win is by being trumps. A key challenge of bidding is to discover which one of the four suits holds the greatest combined length between your partnership, as it will probably be best to make that suit trumps.

When ‘declaring’ (playing the role of the declarer), it’s often good to get rid of the opposition’s trumps near the beginning of the hand so they can’t trump your winners. This is called ‘drawing trumps’. You should avoid continuing playing your trumps (wasting two together) once your opponents have run out of theirs. You therefore need to count.

First work out how many trumps are missing, then think of that missing number in terms of how the cards may be split between the opposition partners, bearing in mind that they’ll usually have approximately the same number as each other. Each time you see an opponent play a trump, mentally reduce the number of missing trumps by one.

In this example, the declarer counts five missing trumps. He cashes ♠K and, when he sees both opponents follow suit, reduces his mental count of missing trumps down to three. ♠2 to ♠Q draws two more of the opponents’ trumps. There’s just one more left out (and it’s now obvious that the split is 3-2). The declarer cashes ♠A, drawing the last trump, and doesn’t need to play a fourth round in the trump suit.

must know

Counting trumps is important. Once you have drawn trumps from your opponents, i.e. exhausted them of their trump cards, you should stop playing in the trump suit and turn to others. Carrying on playing in the trump suit would be a waste because your remaining trumps could probably be made separately, by trumping another suit.

Each bid carries a message and is used to tell your partner what type of hand you have: its strength and which suit(s), if any, you’d like as trumps. Your aim is to outbid the other side with a final bid, a ‘contract’ or trick target, that suits both you and your partner’s hands (hence the term ‘contract’ bridge – see p. 228).

must know

By the end of the bidding, the following will be determined:

• whether the deal will be played in a trump suit (clubs, diamonds, hearts or spades), or without a trump suit (‘no-trumps’ – see p. 27);

• how many tricks need to be made by the side who has bid highest and therefore won the contract; and, by deduction, how many tricks their opponents need in order to stop them from winning;

• which player within the highest bidding partnership is the declarer, and which is the dummy.

The bidding starts with the dealer, who decides whether to ‘open the bidding’. If he has an average or worse-than-average hand, he says ‘no bid’ or ‘pass’. If he has a better-than-average hand (12 points is a good guide), he opens the bidding by stating his preferred suit as trumps – choosing one of his longest suits.

In (a), the dealer says ‘Pass’ as he has only ten points (an average point score as there are 40 points in the pack divided between four players).

In (b), the dealer has 14 points – enough to open the bidding. He has more spades than any other suit, and would like spades to be trumps, so he opens ‘One spade’ (see p. 21, ‘Making a bid at the One level’).

Once the dealer has bid (or passed), the bidding moves to the next player in clockwise rotation. If the dealer has passed, the second bidder now follows the same process as the dealer: with less than 12 points, he passes, with 12 or more he opens ‘One…’ followed by the name of his longest suit. The third and fourth bidders similarly need 12 points to open the bidding. Occasionally, when the high cards are evenly distributed, none of the four players will hold 12 or more points. The deal is then ‘thrown in’, and the next player in clockwise rotation deals with the other pack.

Making a bid at the One level

The number in a bid is the number of tricks to be won above six tricks. There are 13 tricks in each deal, of which a partnership entering the bidding is expected to make at least six (just under half). When making a bid at the One level, e.g. ‘One spade’ if spades is your preferred trump suit, this means you are contracting to make one trick on top of the six, i.e. seven tricks, with the nominated suit as trumps (spades in this example). Bidding usually opens at the One level, but see p. 146for cases where you open above the One level.

Читать дальше