Viktor Rydberg - Teutonic Mythology - The Gods and Goddesses of the Northland (Vol. 1-3)

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Viktor Rydberg - Teutonic Mythology - The Gods and Goddesses of the Northland (Vol. 1-3)» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Teutonic Mythology: The Gods and Goddesses of the Northland (Vol. 1-3)

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Teutonic Mythology: The Gods and Goddesses of the Northland (Vol. 1-3): краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Teutonic Mythology: The Gods and Goddesses of the Northland (Vol. 1-3)»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

One of Rydberg's mythological theories developed in this book is that of a vast World Mill which rotates the heavens, which he believed was an integral part of Old Norse mythic cosmology.

Teutonic Mythology: The Gods and Goddesses of the Northland (Vol. 1-3) — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Teutonic Mythology: The Gods and Goddesses of the Northland (Vol. 1-3)», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

As Jordanes tells us that the Herulians actually were descended from the great northern island, then this seems to me to explain this remarkable resolution. They were seeking new homes in that land which in their old songs was described as having belonged to their fathers. In their opinion, it was a return to the country which contained the ashes of their ancestors. According to an old middle age source, Vita Sigismundi , the Burgundians also had old traditions about a Scandinavian origin. As will be shown further on, the Burgundian saga was connected with the same emigration chief as that of the Saxons and Franks (see No. 123).

Reminiscences of an Alamannic migration saga can be traced in the traditions found around the Vierwaldstädter Lake. The inhabitants of the Canton Schwitz have believed that they originally came from Sweden. It is fair to assume that this tradition in the form given to it in literature has suffered a change, and that the chroniclers, on account of the similarity between Sweden and Schwitz, have transferred the home of the Alamannic Switzians to Sweden, while the original popular tradition has, like the other Teutonic migration sagas, been satisfied with the more vague idea that the Schwitzians came from the country in the sea north of Germany when they settled in their Alpine valleys. In the same regions of Switzerland popular traditions have preserved the memory of an exploit which belongs to the Teutonic mythology, and is there performed by the great archer Ibor (see No. 108), and as he reappears in the Longobardian tradition as a migration chief, the possibility lies near at hand, that he originally was no stranger to the Alamannic migration saga.

19.

THE TEUTONIC EMIGRATION SAGA FOUND IN TACITUS.

Table of Contents

The migration sagas which I have now examined are the only ones preserved to our time on Teutonic ground. They have come down to us from the traditions of various tribes. They embrace the East Goths, West Goths, Longobardians, Gepidæ, Burgundians, Herulians, Franks, Saxons, Swabians, and Alamannians. And if we add to these the evidence of Hrabanus Maurus, then all the German tribes are embraced in the traditions. All the evidences are unanimous in pointing to the North as the Teutonic cradle. To these testimonies we must, finally, add the oldest of all—the testimony of the sources of Tacitus from the time of the birth of Christ and the first century of our era.

The statements made by Tacitus in his masterly work concerning the various tribes of Germany and their religion, traditions, laws, customs, and character, are gathered from men who, in Germany itself, had seen and heard what they reported. Of this every page of the work bears evidence, and it also proves its author to have been a man of keen observation, veracity, and wide knowledge. The knowledge of his reporters extends to the myths and heroic songs of the Teutons. The latter is the characteristic means with which a gifted people, still leading their primitive life, makes compensation for their lack of written history in regard to the events and exploits of the past. We find that the man he interviewed had informed himself in regard to the contents of the songs which described the first beginning and the most ancient adventures of the race, and he had done this with sufficient accuracy to discover a certain disagreement in the genealogies found in these songs of the patriarchs and tribe heroes of the Teutons—a disagreement which we shall consider later on. But the man who had done this had heard nothing which could bring him, and after him Tacitus, to believe that the Teutons had immigrated from some remote part of the world to that country which they occupied immediately before the birth of Christ—to that Germany which Tacitus describes, and in which he embraces that large island in the North Sea where the seafaring and warlike Sviones dwelt. Quite the contrary. In his sources of information Tacitus found nothing to hinder him from assuming as probable the view he expresses—that the Teutons were aborigines, autochthones, fostered on the soil which was their fatherland. He expresses his surprise at the typical similarity prevailing among all the tribes of this populous people, and at the dissimilarity existing between them on the one hand, and the non-Teutonic peoples on the other; and he draws the conclusion that they are entirely unmixed with other races, which, again, presupposes that the Teutons from the most ancient times have possessed their country for themselves, and that no foreign element has been able to get a foothold there. He remarks that there could scarcely have been any immigrations from that part of Asia which was known to him, or from Africa or Italy, since the nature of Germany was not suited to invite people from richer and more beautiful regions. But while Tacitus thus doubts that non-Teutonic races ever settled in Germany, still he has heard that people who desired to exchange their old homes for new ones have come there to live. But these settlements did not, in his opinion, result in a mixing of the race. Those early immigrants did not come by land, but in fleets over the sea; and as this sea was the boundless ocean which lies beyond the Teutonic continent and was seldom visited by people living in the countries embraced in the Roman empire, those immigrants must themselves have been Teutons. The words of Tacitus are ( Germ. , 2): Germanos indigenas crediderim minimeque aliarum gentium adventibus et hospitiis mixtos, quia nec terra olim sed classibus advehebantur qui mutare sedes quærebant, et immensus ultra atque ut sic dixerim adversus Oceanus raris ab orbe nostro navibus aditur. "I should think that the Teutons themselves are aborigines (and not at all mixed through immigrations or connection with non-Teutonic tribes). For those desiring to change homes did not in early times come by land, but in ships across the boundless and, so to speak, hostile ocean—a sea seldom visited by ships from the Roman world." This passage is to be compared with, and is interpreted by, what Tacitus tells when he, for the second time, speaks of this same ocean in chapter 44, where he relates that in the very midst of this ocean lies a land inhabited by Teutonic tribes, rich not only in men and arms, but also in fleets ( præter viros armaque classibus valent ), and having a stronger and better organization than the other Teutons. These people formed several communities ( civitates ). He calls them the Sviones, and describes their ships. The conclusion to be drawn from his words is, in short, that those immigrants were Northmen belonging to the same race as the continental Teutons. Thus traditions concerning immigrations from the North to Germany have been current among the continental Teutons already in the first century after Christ.

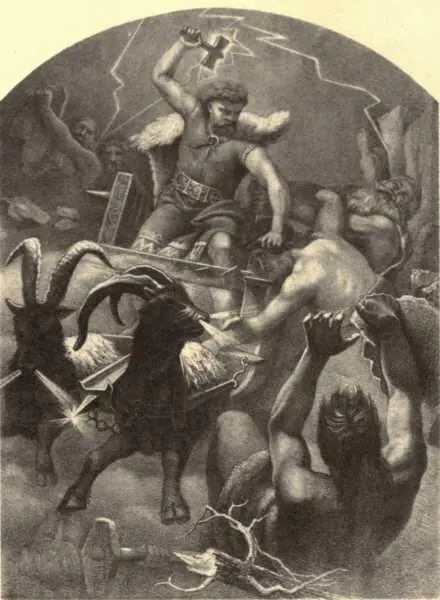

THOR, THE THUNDER GOD. (From the painting by M. E. Winge.) Thor was reputed to be the son of Odin, surnamed the All-father, and Jorth, the earth. He was the source of wisdom, patron of culture and of heroes, friend of mankind and slayer of giants. He always carried a heavy hammer, called The Crusher, with which he fought, assisted by thunder and lightning. From Thor is derived the middle English words Thursday (Thorsday) and Thunder.

THOR, THE THUNDER GOD. (From the painting by M. E. Winge.) Thor was reputed to be the son of Odin, surnamed the All-father, and Jorth, the earth. He was the source of wisdom, patron of culture and of heroes, friend of mankind and slayer of giants. He always carried a heavy hammer, called The Crusher, with which he fought, assisted by thunder and lightning. From Thor is derived the middle English words Thursday (Thorsday) and Thunder.

But Tacitus' contribution to the Teutonic migration saga is not limited to this. In regard to the origin of a city then already ancient and situated on the Rhine, Asciburgium ( Germ. , 3), his reporter had heard that it was founded by an ancient hero who had come with his ships from the German Ocean, and had sailed up the Rhine a great distance beyond the Delta, and had then disembarked and laid the foundations of Asciburgium. His reporter had also heard such stories about this ancient Teutonic hero that persons acquainted with the Greek-Roman traditions (the Romans or the Gallic neighbours of Asciburgium) had formed the opinion that the hero in question could be none else than the Greek Ulysses, who, in his extensive wanderings, had drifted into the German Ocean and thence sailed up the Rhine. In weighing this account of Tacitus we must put aside the Roman-Gallic conjecture concerning Ulysses' visit to the Rhine, and confine our attention to the fact on which this conjecture is based. The fact is that around Asciburgium a tradition was current concerning an ancient hero who was said to have come across the northern ocean with a host of immigrants and founded the above-named city on the Rhine, and that the songs or traditions in regard to this ancient hero were of such a character that they who knew the adventures of Ulysses thought they had good reason for regarding him as identical with the latter. Now, the fact is that the Teutonic mythology has a hero who to quote the words of an ancient Teutonic document, "was the greatest of all travellers," and who on his journeys met with adventures which in some respects remind us of Ulysses'. Both descended to Hades; both travelled far and wide to find their beloved. Of this mythic hero and his adventures see Nos. 96–107, and No. 107 about Asciburgium in particular.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Teutonic Mythology: The Gods and Goddesses of the Northland (Vol. 1-3)»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Teutonic Mythology: The Gods and Goddesses of the Northland (Vol. 1-3)» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Teutonic Mythology: The Gods and Goddesses of the Northland (Vol. 1-3)» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.