Eventually in 2010, the Raumpioniere were essential in realising the citizens’ initiative which proposed to retain the entire former airport grounds as public space. 10The decision was finally ratified in 2014 following a city-wide referendum. The rejection of the existing planning framework amounted to a popular vote by Berliners on development rights to the city. Tempelhofer Feld was to remain open for public use and all forms of development became prohibited.

raumlabor used this referendum as an opportunity to turn a once-temporary neighbourhood centre, the JuniPark, into a long-term project for the purpose of implementing the strategy they had developed under Ideenwerkstatt Tempelhof. 11The resulting Coop Campus is an initiative of Kulturhaus Schlesische 27 and raumlabor. In cooperation with the owners of the land, Evangelischer Friedhofsverband Berlin Mitte, the project continues to develop and examine models for incremental urban transformation of a former cemetery’s terrain vague into a vibrant and diverse urban neighbourhood. The project is made up of sub-projects like Die Gärtnerei Berlin. 12

A response to Germany’s burgeoning refugee situation, Die Gärtnerei examines integration, inter-cultural sharing, housing and urban production through the operation of commercial flower gardens, free language classes and neighbourhood gatherings open to new and long-term residents alike. It is a space that facilitates the integration of ever more diverse actors and stakeholder groups into the incremental enrichment of life in their new city. It descends from the initial aim of Ideenwerkstatt except that it now operates outside the cumbersome and rigid planning mandates of any government body. Projects like this at once circumvent and complement the methods of planning ordinarily employed by government bodies. They require fewer resources and thus entail less risk; more experiments and visions can be tested, thereby creating an inherently flexible planning method. By flipping the traditional value system for built form projects, in these small and experimental approaches to city making there is no really no such thing as failure, merely learning.

Spreefeld balconies.

Photograph by © Andrea Kroth

Spreefeld, Optionsraum.

Photograph by © Andrea Kroth

Berlin liebt dich13

In the past ten years, a number of initiatives and projects have been launched that consider Berlin’s shifting economic and political conditions. Some seek new forms of communal living and working as well as conceptualising alternative forms of project development. Many projects focus on new commons, areas beyond market and state in which people are directly involved in the design of their living environments.

Prinzessinnengarten is an urban community garden established in 2009 as a temporary-use initiative operated by Nomadisch Grün, a non-profit limited liability company. This area of 6,000 square metres once barren land in the middle of the city, is now used to cultivate flowers and vegetables. The plot, owned by the Berlin state government, was and continues to be at risk of privatisation. With the initial lease agreement limited to one year with the option for one-year extensions, the entire garden was conceived as a nomadic operation, exclusively using raised beds made from crates and sacks. Following public pressure via petition, the lease agreement has since been amended to increase the extension term from one to five years. But the Prinzessinnengarten is more than just a space for vegetable crops in the city; it has created a space for a wide spectrum of activities. The potential for cooperation and open workshops along with the garden café and cultural events have made the Prinzessinnengarten a vibrant meeting point. It has also become a beacon beyond its neighbourhood of what can be achieved with collective action in Berlin following its post-reunification privatisation and relative neoliberalisation.

In terms of communal housing, Germany’s healthy culture of Baugruppen (building cooperatives) have made important contributions to the development of new models for urban cohabitation globally. What began as a social model for building and living on the fringe of development tactics, is now gaining recognition in today’s neoliberal landscape as a genuine alternative to the conventional business model of building, for owners and architects alike. There are positive social outcomes for inhabitants and the surroundings whilst owner-occupiers are necessarily invested as active participants in meaningful neighbourhood development.

A successful example in Berlin is the Spreefeld project, located on the bank of the Spree river. The building and housing cooperative founded in 2009, ‘saw its purpose as the creation of housing for cross-generational, socially mixed and neighbourly forms of working and living with sustainable means and to the benefit of its members.’ 14The building cooperative and three participating architecture firms sought to build a community, as a community.

Spreefeld, viewed from Spree River.

Photograph by © Andrea Kroth

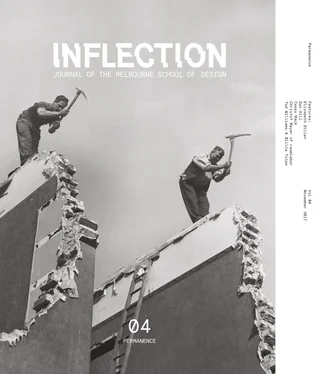

Tempelhof Freiheit in use Photography by © Tempelhof Projekt GmbH, Andreas Labes

JuniPark,

Photograph by © Stefanie Schulz

PenthausBerlin,

Photographs by © Frank Hülsbömer

As a building Spreefeld is a political statement advocating for a socially conscious organisation of housing, where private and public are spatially intertwined. This resulted in deliberate decisions to democratise access to a technically private piece of prime Berlin real estate. Berliners out for a stroll can still reach the bank of the River Spree at any time through Spreefeld’s site. Anyone can apply to use the Optionsräume (optional spaces) on the ground floor regardless of whether they live at Spreefeld or not. These spaces can be used temporarily as exhibition rooms, auditoriums or for workshops, so long as they contribute to the cooperative with programmatic input that is not principally profit-oriented. Living at Spreefeld carries the requisite of participation in the cooperative which governs the apartments and shared spaces. Residents are expected to invest their time, opinions and expertise rather than capital. As a result, rents at Spreefeld are kept at the same level as public housing for those with low incomes, offering a level of security and permanence difficult to find in the conventional rental market.

A more radical approach has been employed by the Mietshäuser Syndikat (apartment-house syndicate), which has been active in Berlin since 2003. The syndicate is a cooperative and non-commercial holding company for the joint purchasing of blocks of rental flats to extract them from the real estate market and provide long-term affordable housing. The syndicate has its origins in the political left as well as the cooperative housing and squatter scenes, and attempts to realistically implement approaches to the socially responsible and ecologically minded handling of money and land. Mietshäuser Syndikat supports and advises projects in financial and legal matters, yet contributes no capital of its own. To date, it has assisted in the acquisition process of 125 apartment buildings (17 of which are in Berlin) equating to approximately 22,500 square meters of living space for 600 people. Adhering to the dominant economic order, this model of activism uses a combination of collective action and capital to liberate capital.

Читать дальше