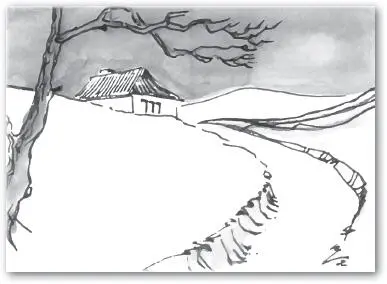

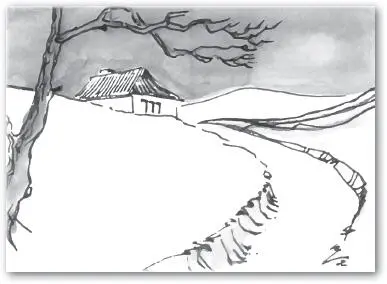

It was the end of March, but it seemed as if winter had come back once more.

At this time of year it was hard not to attract notice in the village. During the summer, visitors arrived daily in their hundreds to wander over the hill, to crowd around the small number of cafes and bars, to buy cheap souvenirs in the stalls and souvenir shops, and to swim at the beach. You could remain unnoticed in the crowd.

But now?

The exposed position of the house meant that no one could approach it without being seen. It was impossible to get to it unobserved. Up to now, everything had seemed clear and simple. Just take the path behind the village at nightfall, go past the old smithy and between the woods and the hill, and then come back between the hedges of bearberry and seabuckthorn.

You would be out of sight of the village.

But now there was snow on the ground and it would betray every footstep. If the snow stayed on the ground, I had made the trip for nothing. Four days – a long weekend – that was all the time I had to find out what had happened.

2

He had disappeared perhaps at the end of September. It is possible that his absence wasn’t noticed right away.

He regularly spent four weeks of vacation abroad, mostly at the height of the season, to stay out of the way of the tourists who, partly out of curiosity and partly in a search for a place to spend the night, pestered him even on his own land. The low wire fence, which ran along the side of the road and then surrounded his place at the top, was ignored by many people who misunderstood the flagstone walk up to the house as an invitation to come in. So he often shut himself in and rarely answered knocks and shouts. If you wanted to talk to him, you had to make arrangements ahead of time.

The slope to the south ran down into a flat basin, then rose to fall gently again toward the village. The wooden posts of the targetstand stood in deep snow on the opposite slope. The lower crosspiece which supported the target barely emerged from the snow. A piece of blue plastic tarp, which had protected the target from rain, fluttered from the upper crossbar. In the low rays of the afternoon sun, the shadows, broken by a rise in the ground, also looked blue.

How long had it been? Three – no, four years. It had been a warm night in June, bright and still. It was one of those nights on the island when it didn’t seem to want to get dark, in which you get a taste of the Swedish midnight sun.

I hadn’t been able to sleep, so I had gone for a walk up the hill. There was a group of tourists standing on the road next to the house staring at the dark slope opposite. A square target with colored rings was illuminated by two flashlights in the grass. Remarkably, the target surface seemed to float above the black background of the lawn. Two men sat under the birch on the terrace next to the house.

A third man stood to one side unmoving, a bow in his hand with a glint of metal coming from the clumsy-looking middle section. The man had set the end of the bow on his left foot and was staring at the target, which seemed to be on the same level as his position. As he bent down, I saw some arrows sticking in the grass in front of him. He nocked an arrow and, facing the target, raised the bow, drawing it in a smooth motion. The light thrum of the bowstring as he shot was followed almost immediately by the dry impact of the arrow on the target. A black V-shaped shadow had appeared suddenly in the gold spot in the middle of the target. Before I realized that the two lights at the foot of the targetstand threw the shadow of the arrow shaft across the target at the same angle, the sounds of the shot and impact were repeated. Once more in the gold, a little lower, and now the shadows intersected to form a large W with its upper joint pointing into the darkness above the upper edge of the target.

The man nocked a third arrow. It seemed that his movements were always at the same pace. This arrow too landed in the illuminated golden spot, and the shadows of the three arrows now formed an angular gridwork across the gold.

The man laid the bow in the grass and went down the slope to the target. In the lamp light he seemed to be a small man rather than of middle size. Barefoot, in jeans and a dark T-shirt, he pulled the arrows out of the target without apparent effort. He bent down to the flashlights, which went out immediately, and then walked slowly back to the house, carrying the arrows in his hand. He sat down next to the two men on the terrace, who now bent over his bow, which he held across his knees. I stood next to the house, about twenty meters away and watched the men talking quietly. I couldn’t understand anything they said.

The group next to me, who, like me, had watched silently, was getting ready to leave. As they passed me, I asked, “Excuse me, do you know that man?” “The one with the bow?” I nodded. It seemed that they had seen this kind of thing often. “He makes those things here. But you can’t buy them.”

They went on. I looked back at the target. My eyes had adapted again to the diffuse lighting in which the target, now light gray, stood in front of the dark grassy slope. I had the impression of a staged effect as I recalled the scene which I had just seen. But it had been unusually fascinating.

I wasn’t interested in archery. On television I had seen men in wheelchairs who shot at targets in gyms. I regarded it as a sport for the disabled or for children, and I couldn’t imagine that anyone could take it seriously. It seemed to me to be a waste of time, but it fit my image of the island.

And I wanted to get to know the man who shot at the colorful target at night. And that was how it began, four years ago.

3

The wind picked up. It came in gusts across the bay and raised glistening clouds from the rose hedges, whose brown twigs stuck up from beneath the snow. I turned my back to the wind and pulled up the collar of my jacket. I was freezing.

Slowly I went back down the path I had taken. In the harbor inn I drank a grog, then another. Outside it had gotten dark. When I pressed my face close to the black windowpane, I could see the masts of the fishing boats sway. The halyards on the flagpole in front of the inn smacked against the wood in a broken rhythm. Fishermen drinking rye and beer sat at two tables next to the bar. When I had first come in, they had looked up at me silently. Then they began talking again. A group was playing skat at their usual table. Their black sailor caps lay on the chairs next to them. The only woman in the room was the tired looking barmaid, who was leaning on the counter behind the bar. Only the murmur of voices and the slap of the cards on the wooden table could be heard in the half-dark room.

With warmth came fatigue. I paid and went up to my room. I stood in the dark room, leaning next to the door. The light from the courtyard outside cast the tangled shadows of a tree against the ceiling above the window. In the sharply defined rectangle of light, the chaotic images of the twigs danced with the irregular gusts of wind. Waves crashed heavily against the breakwater of the mooring basin. The featherbed was damp and heavy. The room hadn’t been heated before afternoon. I got up once to put on some wool socks, which I took out of my traveling bag beside the bed. Then I went to sleep.

During the night, there was a change in the weather. I woke up when the rain began to beat against the window, and I thought of the house on the hill before I went back to sleep. The morning was overcast and gloomy. The wind had died down and it was raining. The view from the window reached only to the harbormaster’s house, then everything vanished into an ashy gray. A thick curtain of raindrops obscured the rain and the water in the harbor. I went back to bed and slept until about noon.

Читать дальше