As mentioned in Chapter 6, the inventor cannot obtain a patent if the differences between the subject matter sought to be patented and the prior art are such that, at the time a patent application is filed, the subject matter as a whole would have been obvious to a person having ordinary skill in the art to which the subject matter pertains. Thus, you must furnish sufficient information to the patent attorney as to the relevant prior art and prior activities that you are aware of to allow the patent attorney to determine whether or not any differences between your invention and the prior art could be considered obvious. This is a cost benefit consideration, since it is folly to file a patent application where you are advised that a patent may never be obtained because the differences between the invention and the prior art would be obvious to one skilled in the art.

A patent application must be drafted so that one skilled in the art can read the issuing patent 20 years from its date of filing and reconstruct the invention, without undue experimentation, from the information contained in the patent. If such complete information is not presented, the patent itself may be declared invalid by a court of law when attempted to be enforced against an infringer, on the basis that the patent itself eliminates certain essential material that is necessary to enable one to practice the invention. Therefore, it is not wise to hold back secret information from the patent attorney which would be required to furnish a complete operating working paper on how to reconstruct and operate the invention in the patent application. The enablement requirement has been very strictly construed by the courts in recent decisions, and a lack of an enabling disclosure has been the basis for invalidating several patents. Therefore, it is important to remember the enablement requirement when providing descriptive information that goes into the patent application. Keep in mind also that technical details such as dimensions, sizes, angles, materials and the like need not be set forth in the patent application, unless these details are relevant to the operation, novelty, or non‐obviousness of the invention.

7.4.11 The Best Mode Requirement

Since the patent statutes require that the “best mode” of the invention contemplated by the inventor at the time of filing the patent application be described in the application as filed, you, as the inventor, must describe to the patent attorney the best mode of carrying out the invention as of the date of your invention disclosure meeting. You must also keep your patent attorney advised of further significant activities in the progress of developing the invention while the patent application is being prepared, so that, on the filing date, the application will contain the best mode of the invention. This may require that you, the inventor, take a day off work to allow the patent professional to complete and file the application before you make any further improvements.

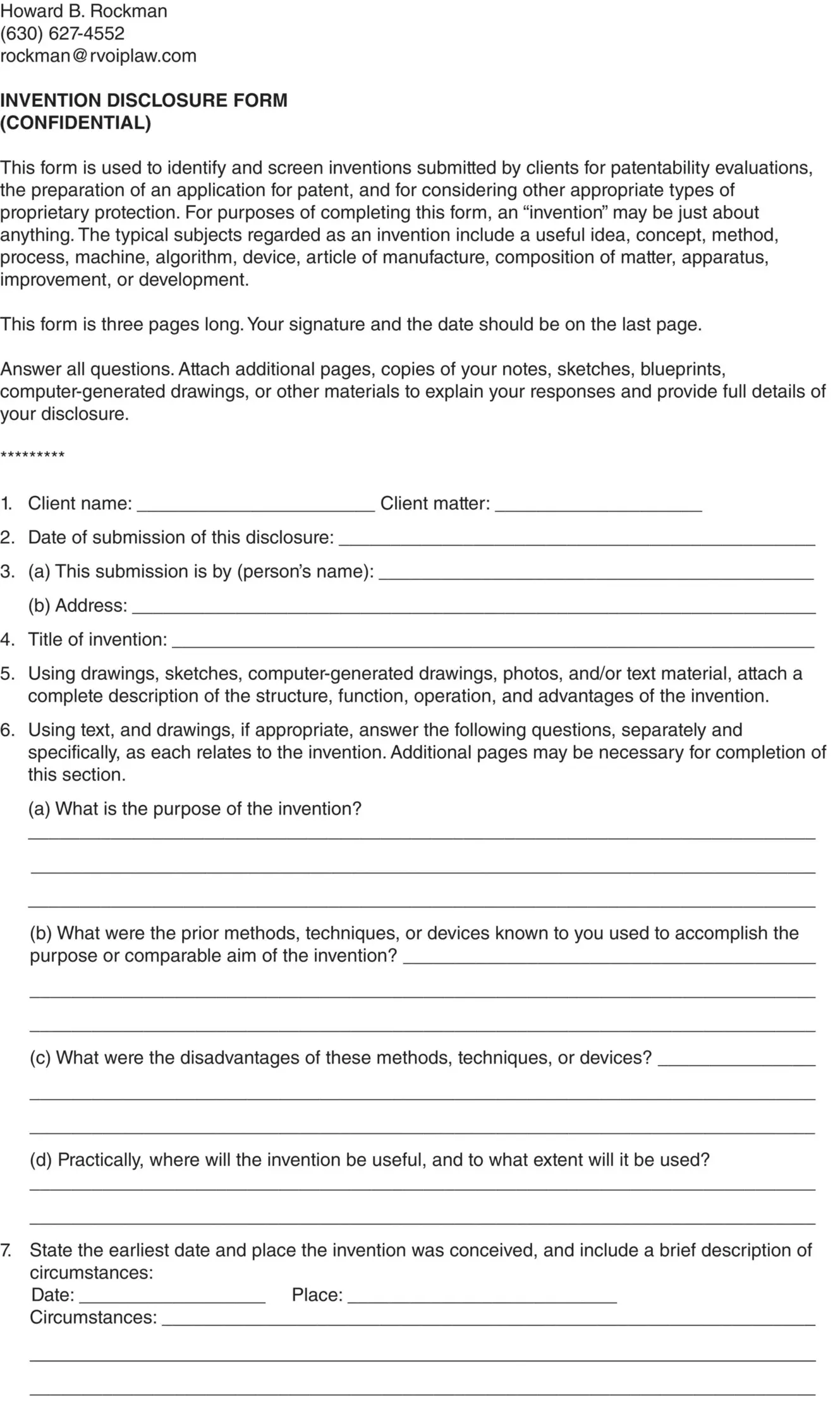

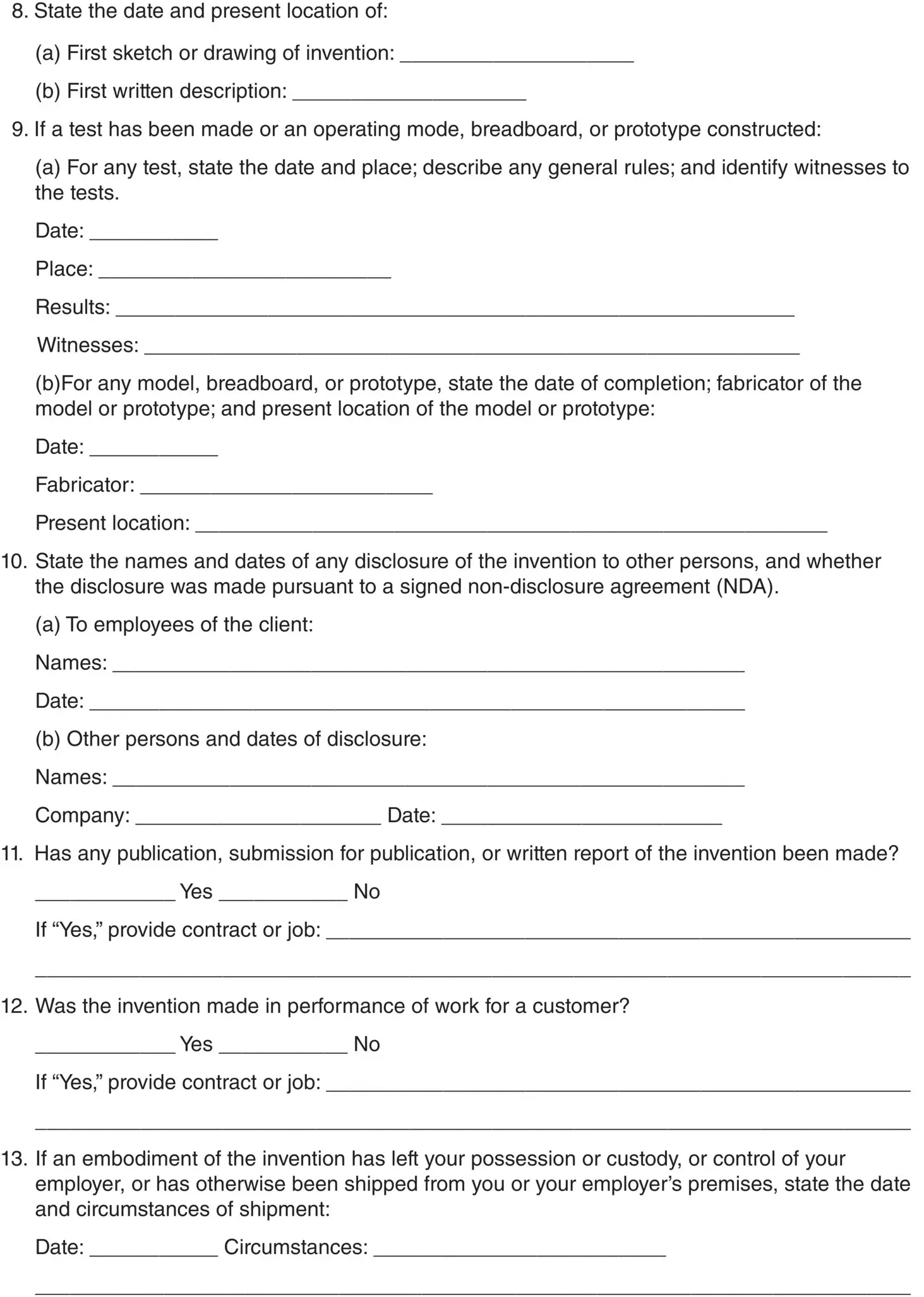

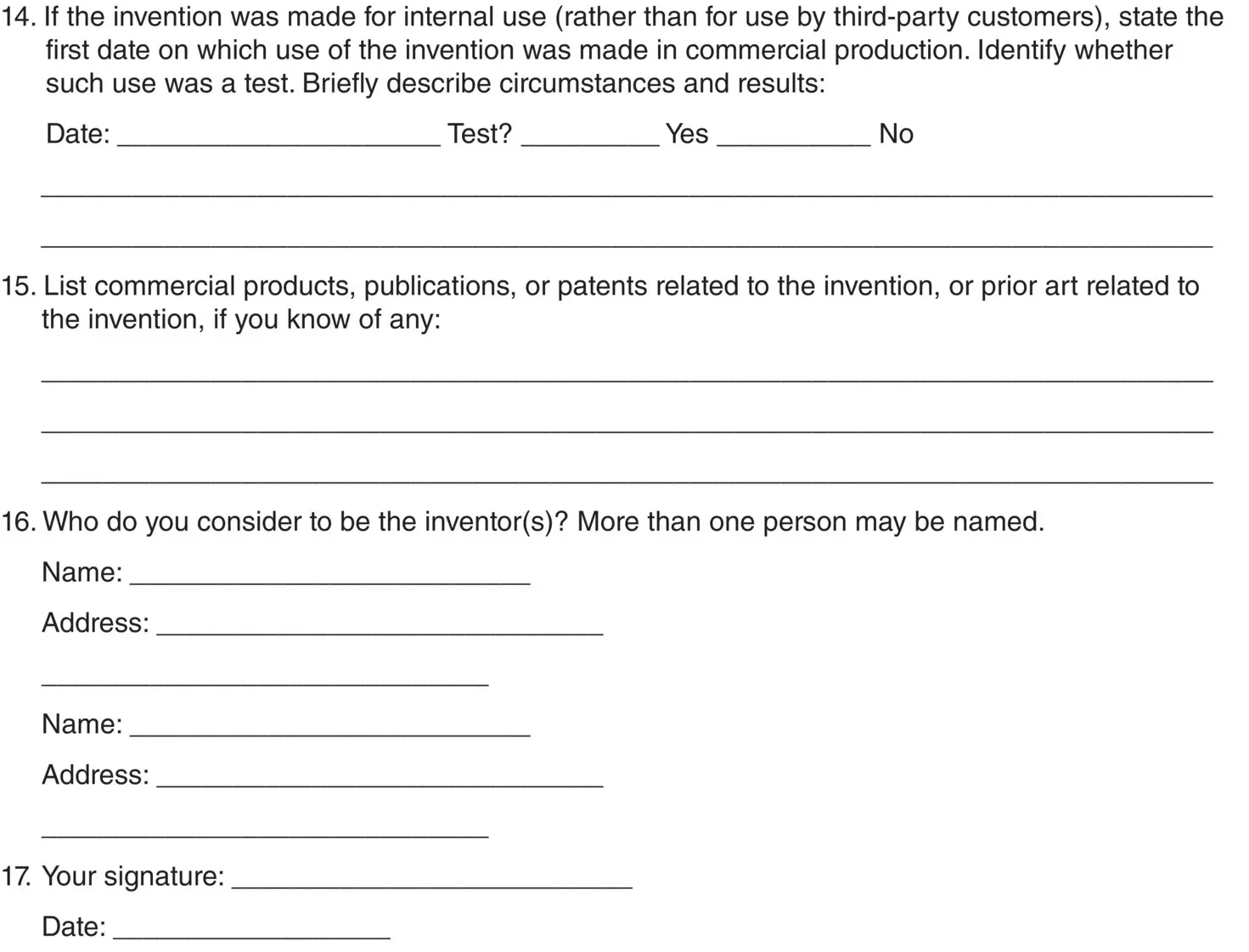

7.5 INVENTION DISCLOSURE FORM

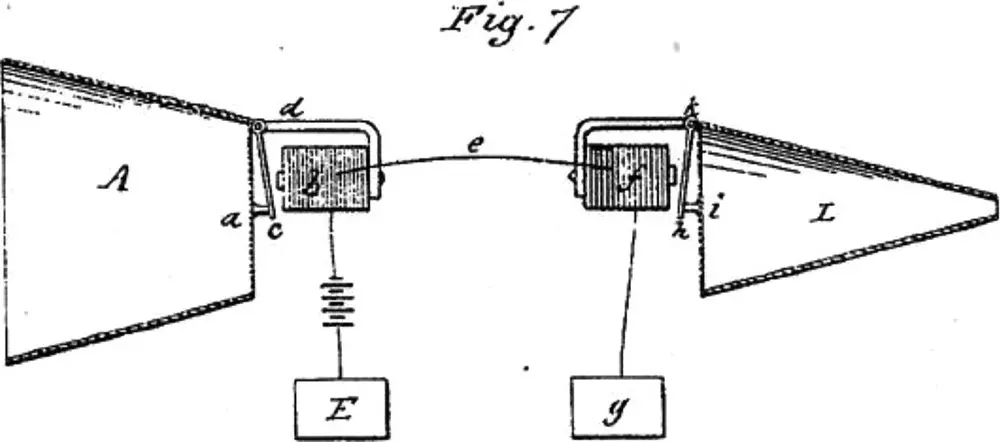

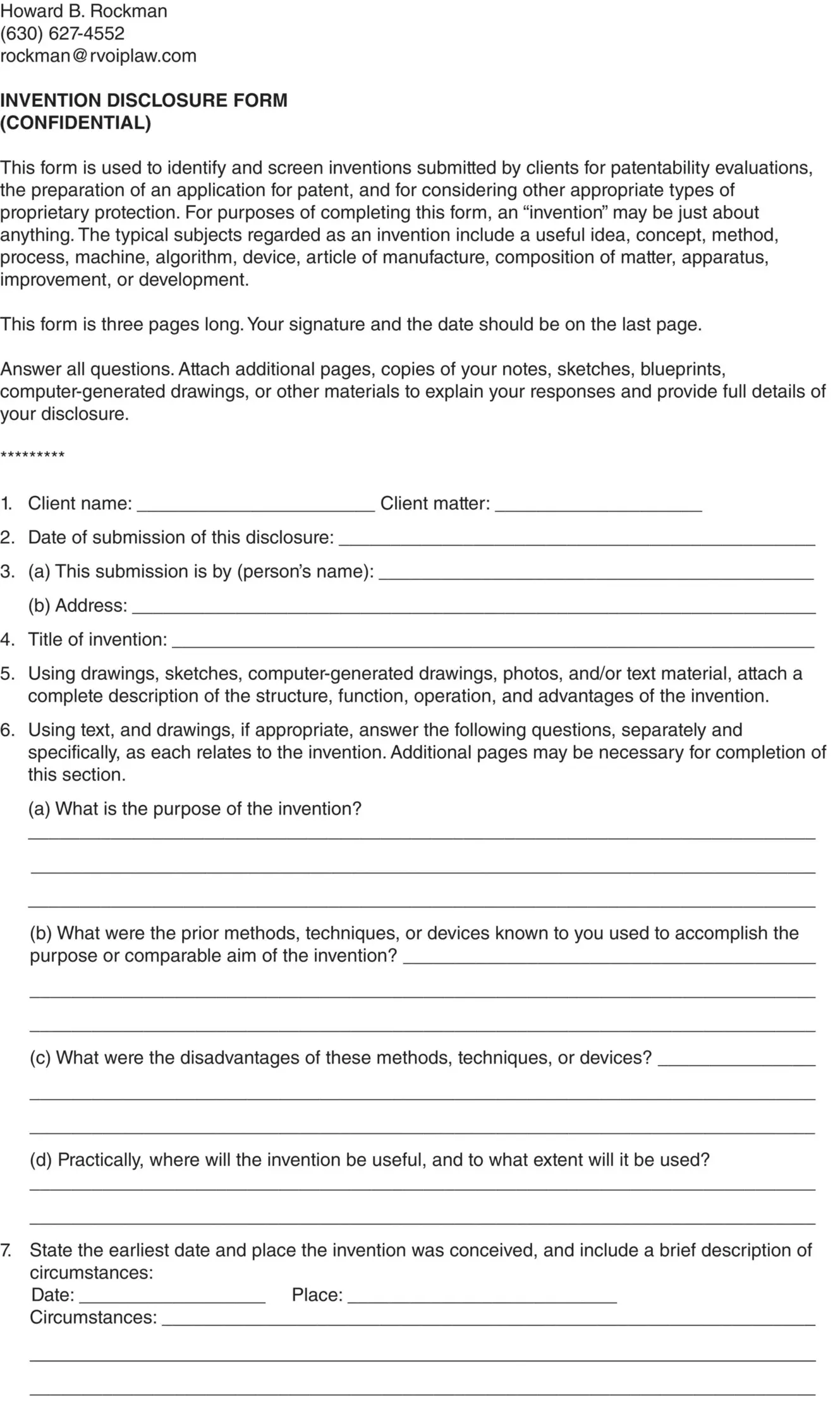

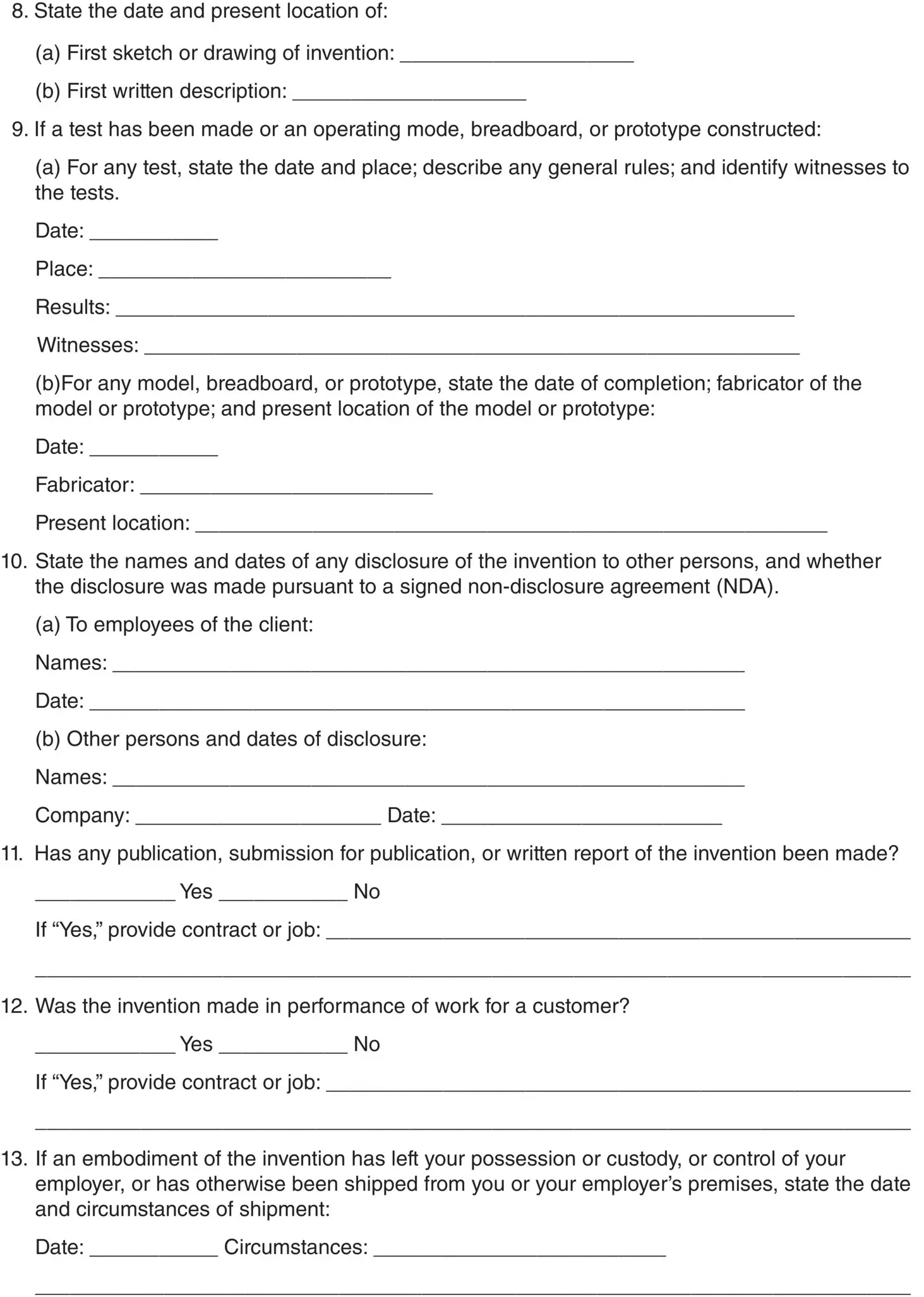

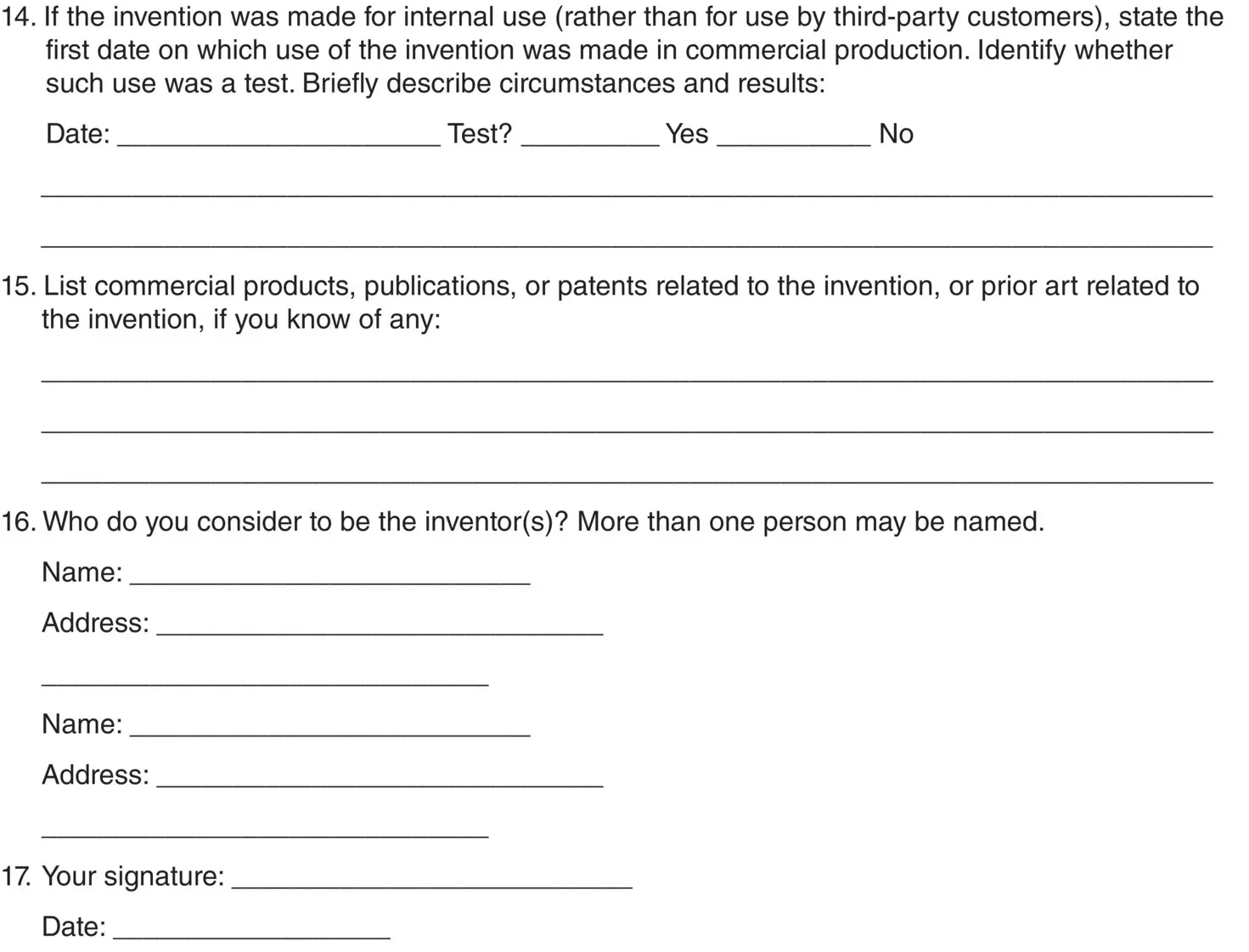

At the end of this chapter is a sample invention disclosure form ( Fig. 7.1) that I use quite often in my practice, which should be completed by the inventor prior to the first invention disclosure meeting, and then brought to the meeting for discussion. Better yet, the disclosure form and materials should be forwarded to the patent attorney prior to the meeting. This will shorten the meeting, and provide the patent attorney with most of the information for review prior to the meeting. Also, the inventor should come to this meeting with all prints, drawings, sketches, photos, and written and electronic material that describe the structure, operation, and advantages of the invention.

Figure 7.1 Sample invention disclosure form.

INVENTORS AND INVENTIONS

Alexander Graham Bell

TELEPHONE

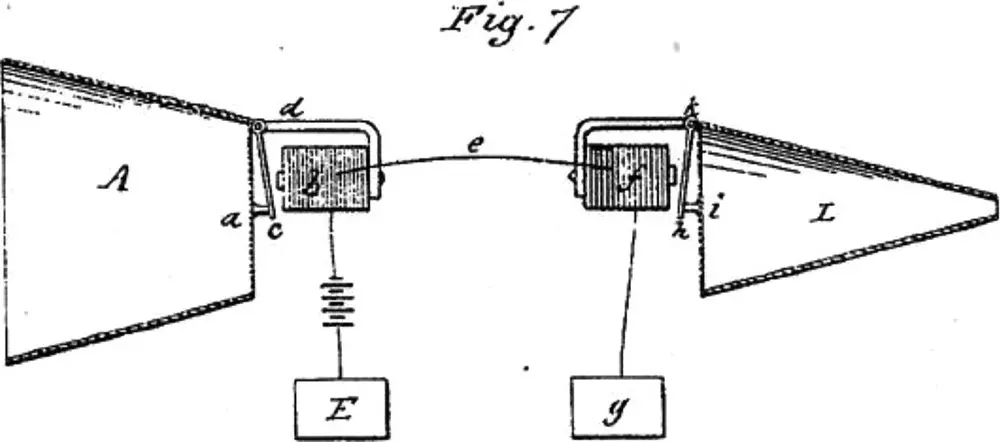

Alexander Graham Bell is credited with inventing the practical telephone, which can be defined as a device for transmitting human speech by electricity. The history of the development of the telephone shows that there were several others working on similar projects at the same time, such as Elisha Gray and Thomas Edison. For example, in the United Kingdom, some consider Gray as the telephone’s inventor. As a result, the U.S. patent that was ultimately issued on Bell’s telephone, and his ensuing telephone patents, were the subject of 600 patent infringement lawsuits, all won by Bell, and all upholding his patents.

Alexander Graham Bell was born in Edinburgh, Scotland, on March 3, 1847. His father, Alexander Melville Bell, was a teacher who taught deaf and mute students how to speak. Bell’s father also created a code of symbols, indicating positions of the lips, tongue, and throat in making sounds, helping the deaf learn to speak. This was known as “visible speech.”

Alexander’s mother, Eliza Bell, was practically totally deaf, and by pressing his lips against his mother’s forehead, Bell discovered that he could make the bones in her head resonate to his voice. Bell was also a talented pianist who learned early on to define and discriminate pitch. He noticed that a chord struck on one piano would be echoed by a piano in another room, and that entire chords could be transmitted through the air, vibrating at the receiving end at the same pitch as transmitted. This observation eventually was involved in the development of the telephone.

After Bell’s oldest and youngest brothers died of tuberculosis in Scotland, the family moved to Tutelo Heights, near Brantford, Ontario, Canada. Bell’s father subsequently took a position in Boston, Massachusetts, teaching deaf children to speak, and his son began a successful teaching career in Boston. His students included George Sanders, the son of a successful leather merchant, and Mabel Hubbard, the daughter of a successful lawyer. Later in life, Mr. Hubbard and Mr. Sanders were to become Bell’s chief financial backers, and Mabel Hubbard became his wife.

The early experiments of Bell that eventually led to the invention of the telephone did not even involve thinking about a telephone. Bell was trying to develop a multiple telegraph, one that could be used to convey several messages simultaneously, each at a different pitch. Telegraphy at that time involved transmission of an electrical current that was interrupted in a pattern known as the Morse Code. In the 1870s, Bell, Edison, and Elishia Gray were all seeking a telegraph device that could send upward of four messages simultaneously. Bell’s work on his multiple telegraph stemmed from Helmholtz’s device, which used a single tuning fork that continually interrupted the circuit and a resonator that kept the other tuning forks in the system in constant vibration. The Helmholtz device was used to produce vowel sounds using electromechanical means, and Bell assumed that if the vowels could be transmitted over wires, so could other sounds, including the consonants and musical tones.

Читать дальше