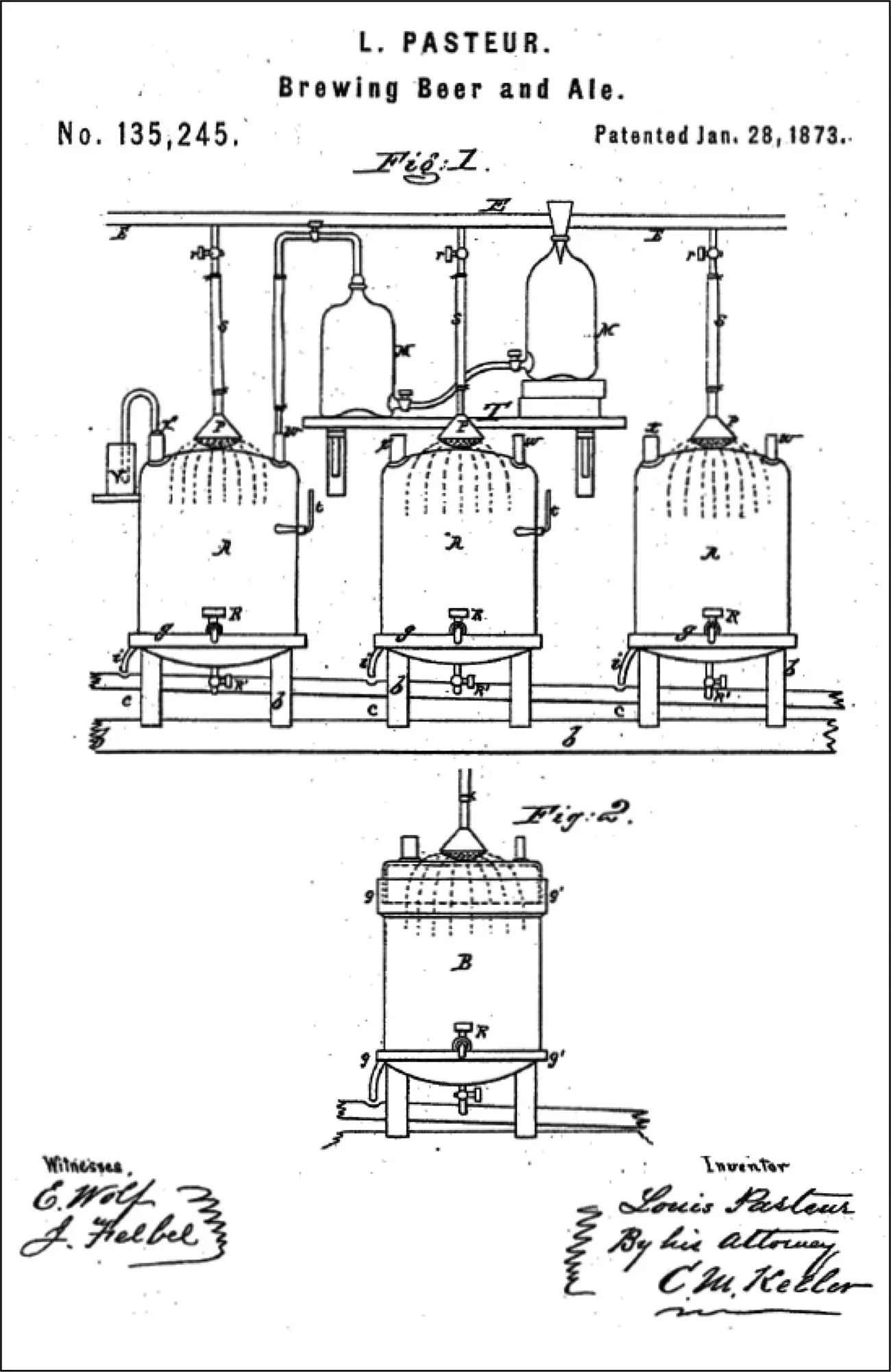

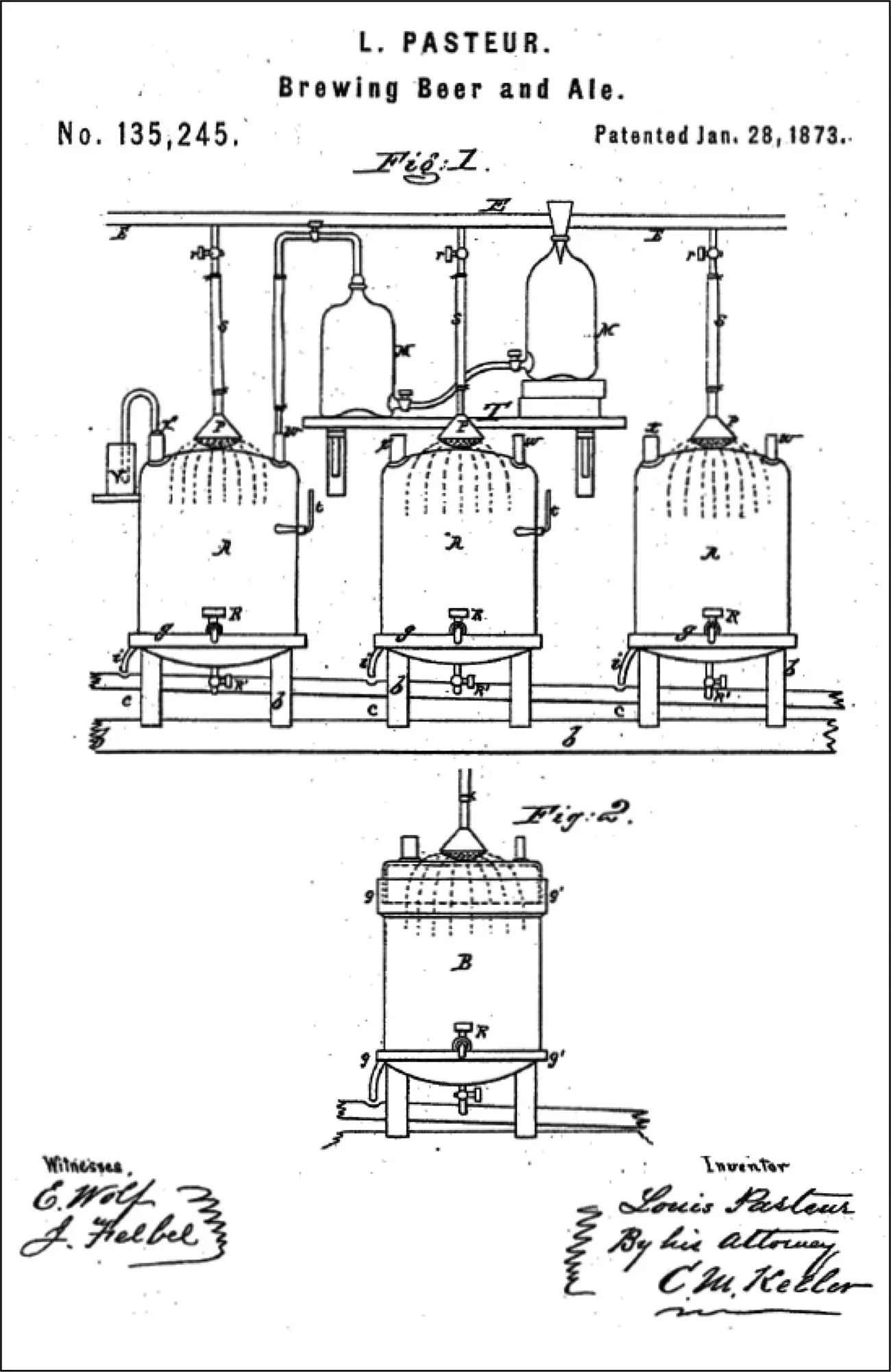

Over the next several years, Pasteur isolated and then identified specific microorganisms that led to both abnormal and normal fermentations in wine, beer, and vinegar production. He determined that if wine, beer, or milk were heated to moderately high temperatures for a short period of time and then cooled, living microorganisms could be killed, thereby sterilizing (later known as pasteurizing) the fermentation batches and preventing their degradation. Thus, if microbes and yeasts in pure cultures were added to sterile fermentation masses and air was prevented from entering the vats by sealing them, predictable fermentation would follow.

Pasteur’s earlier work on crystallography, chemistry, and optics led him to formulate the theory that asymmetric molecules are the result of living forces, and his work developed the new science of stereochemistry. In his work on fermentation, he demonstrated that each type of fermentation is caused by the existence of a specific microorganism or ferment, which is a living organism that can be studied through cultivation in a sterile medium. This is the basis of microbiology today.

Following his work in fermentation, and his discovery that the living microorganisms could be controlled to prevent the spoliation of products, Pasteur went on to a successful career as a chemist, with several major discoveries to his name. For example, he debunked the theory of spontaneous generation, which held at that time that microbes could be generated spontaneously from spoiling matter. Through his work on fermentation, he proved that microorganisms found during fermentation and putrefaction came from the outside, such as from dust in the air, and destroyed every theory that supported the spontaneous generation argument. He also concluded that microscopic beings are generated from parents similar to themselves.

Pasteur went on to research and cure a devastating disease among silkworms that was destroying the French silk industry. He also discovered the germ theory of disease and the use of vaccines in humans to prevent those diseases. It was only through the teachings of Pasteur, Lister, and others that antiseptic medicine and surgery began saving many lives. Pasteur also made major advances in dealing with anthrax, rabies, and the use of vaccines in humans.

While experimenting with biochemical agents for use against an increasing rabies infection epidemic in France, Pasteur discovered that contagions were the cause of disease. He also identified different germs that were present in the human body during illness. With this information, he found the causes of several diseases, and also discovered how to protect uninfected people through the use of vaccines that he ultimately developed. Pasteur made successful vaccines for diphtheria, tetanus, anthrax, chicken cholera, silk worm disease, tuberculosis, and the plague. In 1858, he proved garlic could be used as an antibacterial agent, which he ultimately gave to people who were seriously ill or had developed plague. His work on sterilization in medical procedures was slow to be adopted by many hospitals, but during his lifetime he spent much of his time working in hospitals with doctors trying to find ways to sterilize the equipment and the rooms in which operations were performed.

In 1885, Pasteur was working on experiments with rabies vaccines involving dogs, but had not used the vaccine on humans because he was afraid of unanticipated results and his inability to isolate the substance causing rabies. However, as in the development of all significant scientific discoveries and inventions, fate played its hand. A 9‐year‐old, Joseph Meister, appeared in Pasteur’s laboratory on July 6, 1886, with his mother. The young boy had been bitten by a rabid dog, and he could hardly walk. Pasteur, up to that time, had successfully treated 40 dogs, but had never used his vaccine on a human. Pasteur then consulted with many of his physician colleagues, and with much hesitation and reluctance treated the youth with his vaccine. Joseph Meister recovered, and lived a long and healthy life. Following this, people bitten by rabid dogs in many countries, including Russia and the United States, came to Pasteur for treatment. Newspapers reported these treatments and cures with overwhelming interest, making Pasteur a legend. Funded by public and governmental funds, the Pasteur Institute was created in Paris, initially to treat victims of rabies. Eventually, other Pasteur Institutes were built, including three in the United States, to treat rabies and other diseases.

The treatment of rabies was the last major project of Louis Pasteur. At the age of 46, he suffered a serious stroke, and his general health began failing. After suffering additional strokes, he died in 1895.

INVENTORS AND INVENTIONS

Elisha Otis

SAFETY ELEVATOR

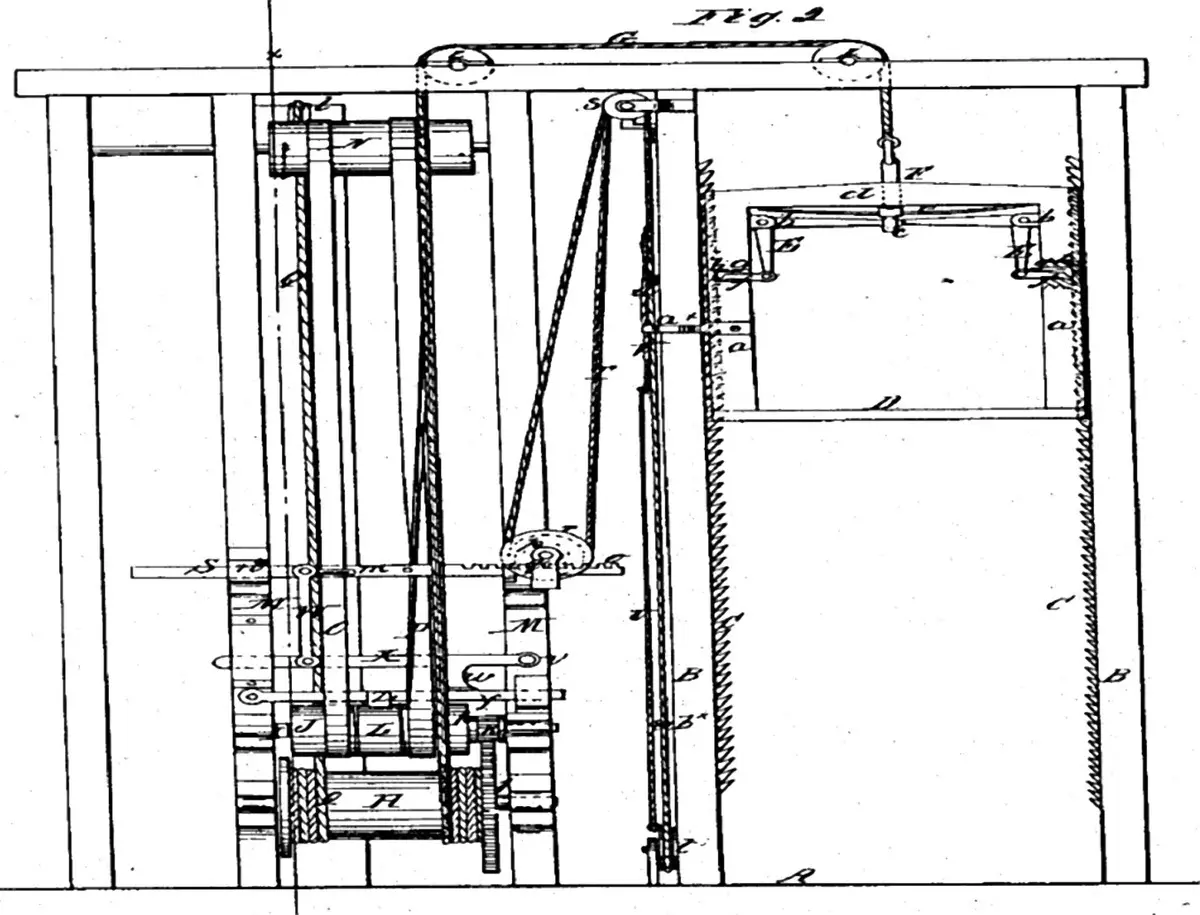

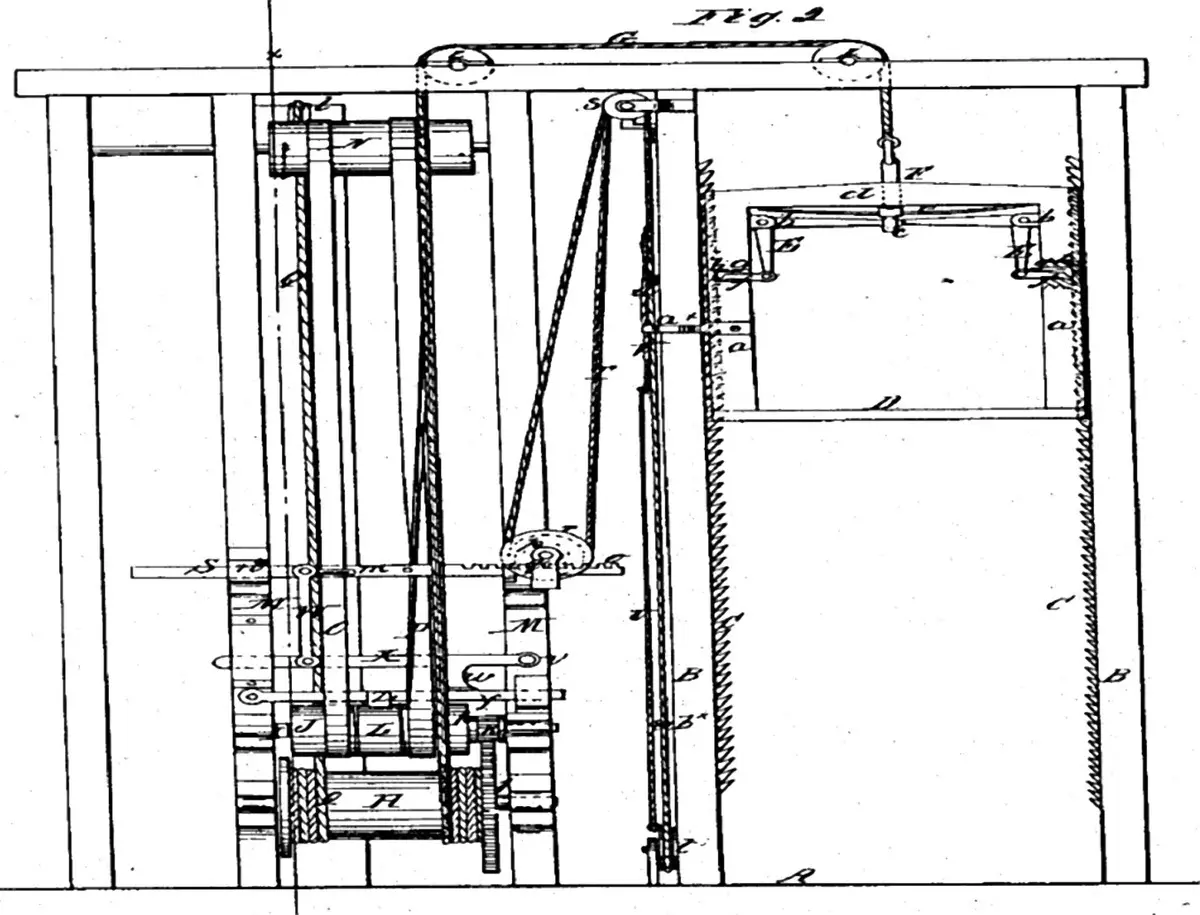

Elisha Graves Otis was an American industrialist and founder of The Otis Elevator Company. Practically everyone reading this essay has been on an elevator and seen the name Otis; however, Mr. Otis did not invent the elevator. He is famous for inventing a safety device that prevents elevators from falling if the hoisting cable fails.

Throughout the centuries, humans have employed many, many ingenious forms of elevating people, animals, and a variety of loads. The earlier lifts used man, animal, and water power to raise loads. In ancient Greece, Archimedes developed an improved lifting device operated by ropes and pulleys, where the hoisting ropes were coiled around a winding drum operated by a capstan and levers. By C.E. 80, gladiators and wild animals rode crude elevators up to the arena level of the Roman Coliseum.

Early elevators were open cars comprising a platform using hoists that were difficult to move vertically. The hoists were typically worked manually by people or animals. Where available, water wheels and water power were employed for the hoisting.

The first elevator designed for a human passenger was built in 1743 for King Louis XV of France. His elevator went up only one floor from the first to the second, and was known as the “flying chair.” It was outside of the building, and was entered by the King from his balcony off his apartments. The mechanism comprised a carefully balanced arrangement of weights and pulleys deployed inside a chimney. Men stationed inside the chimney raised or lowered the flying chair at the King’s command, who used it primarily to visit his lady friend’s apartment on the second floor, as some literature has indicated.

In the 1800s elevator technology began to move forward, and they no longer had to be worked manually. For example, in 1823, two British architects built a “steam powered ascending room” to take tourists up on a platform for a view of London. Several years later, their invention was expanded upon by other architects, who added a belt and counterweight to the steam tower. Eventually, hydraulic systems using water pressure to raise and lower the elevator car were designed and constructed. Hydraulic elevators were safer, but steam‐powered elevators also remained. Accidents occurred when the cables holding the elevator aloft snapped. The public was not enthusiastic about getting on these dangerous elevators, so passenger elevators were basically just a novelty.

One Otis Tufts patented an elevator design with doors that opened and closed automatically, and had bed seats inside. However, his design did away with the typical cable system because of safety issues, and instead employed what we consider an impractical and expensive system of threading the elevator car vertically upon a giant screw. Can you imagine what the cost would be in today’s tall buildings?

Читать дальше