1 ...7 8 9 11 12 13 ...21

Literary Relationships: Which Came First – Jude or 2 Peter?

It has been noted through the centuries that there is an extremely close relationship between 2 Peter and the epistle of Jude. In fact, 2 Peter 2 includes almost the entire epistle of Jude. Hence, it is not surprising that the question must be considered as to which epistle was written first. The major similarities are between Jude 4–13, 16–18 and 2 Peter 2: 1–18, 3: 1–3. Although some of the material is extremely similar, the treatment of it by each author is significantly different, for example, whereas Jude describes the heresy and false teachers in his community using a series of three Old Testament examples to make his points, the author of 2 Peter structures his letter around the main issue of the certainty of the coming final judgment which is being distorted by the false teachers. However, much of Jude’s material is interwoven through Peter’s chapter.

Four explanations are logically possible; all of them are held by outstanding scholars. The problem is that although each of them has some strong supporting evidence, none is so strong that it conclusively discounts the others. Similarly, each can be adequately opposed but not so conclusively that it can be withdrawn as a possibility. Hence, the challenge remains for every serious scholar to come to their own conclusion on the relation of these two texts. Whatever position one accepts, it remains a significant issue, and has some consequences for dating, although other factors must be considered as well. The four explanations are:

1 Jude is dependent on 2 Peter. Many of the ancient writers as well as Luther hold this position. Noteworthy modern scholars include Spitta (1885: 381–470), who has the most details, Zahn (1901: 250–251, 265–267, 285), and Bigg (1961: 216–224).

2 2 Peter is dependent on Jude. Most modern scholars hold this position. See Mayor (1907: i–xxv) for the most detailed argument; Chaine (1939: 18–24); Grundmann (1974: 75–83), and Bauckham (1983).

3 Both are dependent on a common source. Some adherents to this position are Reicke (1964: 148, 189–190). There are serious problems with this option since no such possible source has ever been located (for details see Bauckham, 1983: 141).

4 They share common authorship. See Robinson (1976: 192–195). This option, however, is highly unlikely on account of the epistles’ vast differences in style and very few if any current scholars adhere to this view.

The consideration of the literary relations between the two texts provides the strongest reason for the dependence of 2 Peter on Jude rather than the reverse: the most compelling one is that Jude 4–18 is meticulously crafted in structure as well as wording (see Bauckham, 1983: 142 for details, and Neyrey’s 1993 “Introduction” for his analysis of Jude’s unusual pattern of threes). An additional factor to be considered is the redaction of the parallel passages which has been done by Fornberg, 1977: ch. 3, and Neyrey, 1980: ch 3; see Bauckham, 1983: 142–143 for a thorough analysis of this evidence with its strengths and weaknesses. A further exploration into this issue goes beyond the purview of this current study, but it hardly needs to be undertaken given the treatment of Bauckham along with the redaction critical studies of Fornberg and Neyrey already mentioned. Several important points concluded by Bauckham are noteworthy here:

1 The case for the dependence of 2 Peter on Jude is a strong one, although in some instances it can be countered by evidence from an analysis of the reverse.

2 The late dating of 2 Peter is not a consequence of this relationship. There are other relevant factors which call for a date later than the death of Peter (e.g. the situation in the letter) which have nothing to do with the relation to Jude. Jude could be dated earlier or later than 2 Peter and the evidence would still indicate a late first‐century or early second‐century date for 2 Peter. Again, there are many commentators who address this issue more than adequately, so the details do not need to be recorded here. A brief overview of the main factors are located in Appendix 1.The literary relationship between these two texts does not necessitate the conclusion that these epistles are similar works, addressing the same problems, issues, and readers or with the same historical contexts. In fact, the opposite has stronger supporting evidence, that they are indeed two very different texts, with different historical backgrounds, readers, problems, and heresies. The fact that one of them has reworked some of the other’s material is a separate matter altogether. (Again, for details on all of these discussions, see Neyrey, 1980, Fornberg, 1977, and Bauckham, 1983.)

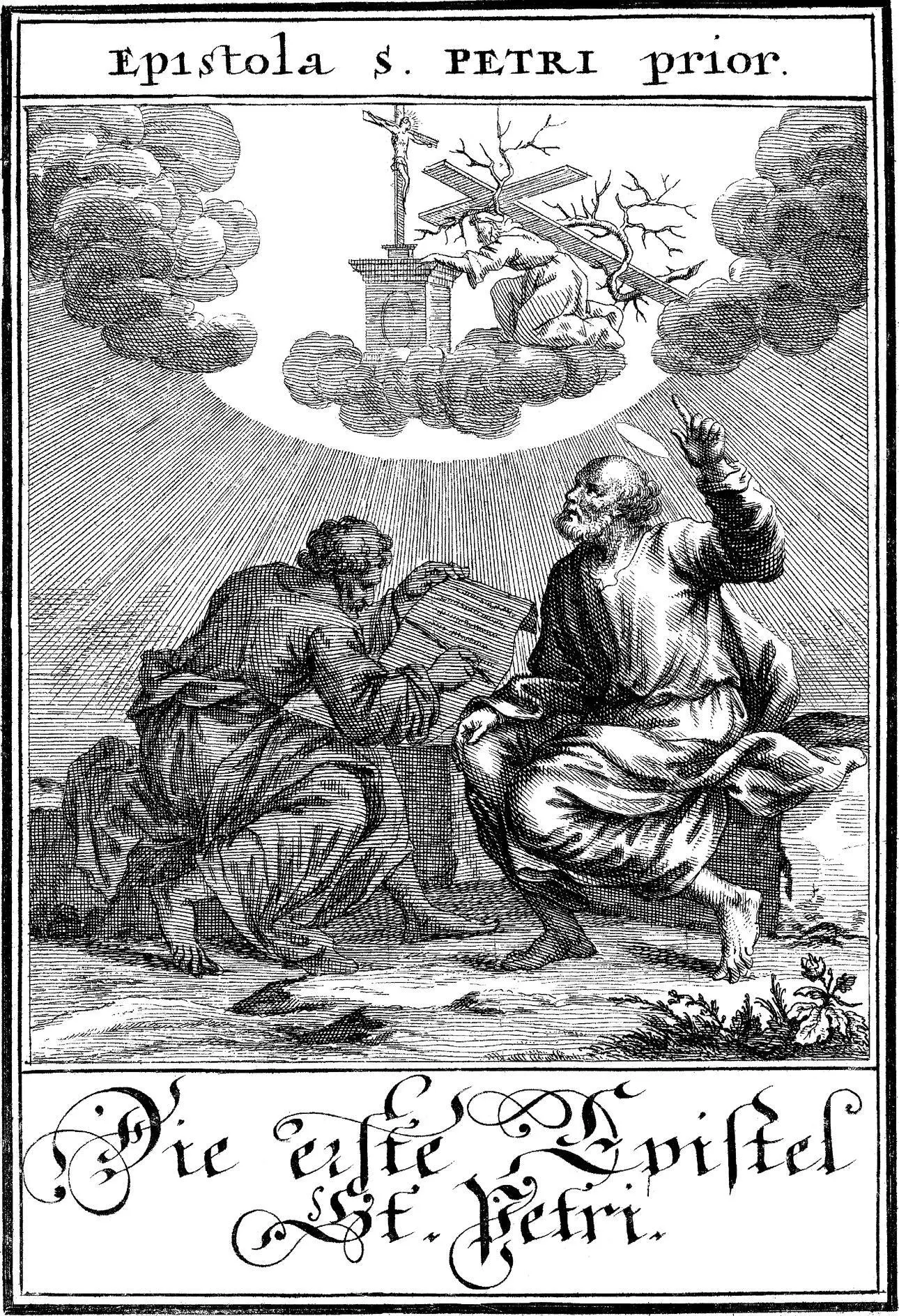

“Correspondence of 1 Peter” (woodcut by Weigel, 1695). Courtesy of the Pitts Theology Library, Candler School of Theology, Emory University.

Chapter 1 The Transformed Life in the Context of Suffering, Grace, Hope, and Love (1:1–2:10)

Author, Audience, and Abundant Grace (1:1–2)

Overview

The beginning of the epistle sets both the author and the readers within the framework of one of the issues which would stimulate future theological controversy and excitement, viz., the foreknowledge of God. These verses are a striking example of the advanced level of the Greek grammar and style of the epistle. They are comprised of one sentence (two, if you count the grace‐and‐peace blessing as one), followed by three dependent clauses describing the nature of Peter’s apostleship and the character of the recipients’ relation to the triune God:

according to the foreknowledge of God.

through the sanctifying work of the Spirit.

for obedience to Jesus Christ and sprinkling of his blood.

Some of the fathers, among them Cyril of Alexandria (375–444), Oecumenius (d. 990), and Theophylact (c. 1050–1108, Comm. on 1 Peter ), read these three prepositional phrases in v.2 as modifying “apostle,” thus substantiating the authority of Peter’s apostleship. On the other hand, Bede associates God’s foreknowledge with the recipients: “they were chosen … [so] they might be sanctified” ( Comm ., 1985: 70). In any case, the intriguing issue is God’s foreknowledge. Of course, the famous controversies about predestination and free will would be further developed in the later Reformation with Calvin, Arminius (1560–1609), and many others.

At an earlier time (c. 200–300), interest centered on the nature of God’s knowledge and what that meant. For example, Origen discusses this in the context of the role of the Spirit in the Trinity, especially in revelation:

We are not, however, to suppose that the Spirit derives His knowledge through revelation from the Son. For if the Holy Spirit knows the Father through the Son’s revelation, He passes from a state of ignorance into one of knowledge; but it is alike impious and foolish to confess the Holy Spirit, and yet to ascribe to Him ignorance. (Origen, 1973, 1:3–4: ccel.org)

For Didymus the Blind (313–398) foreknowledge is a matter of perspective; he comments that “foreknowledge … becomes knowledge as the things which are foreseen take place.” So, although Peter’s readers had already been chosen according to God’s foreknowledge, “by the time he was writing to them their election had already taken place” ( Comm. on 1 Peter, 19–20, PG 39: 1755–1756: my tr.).

Perhaps Didymus anticipates the larger issue to come regarding predestination, since he addresses some of the problems raised later. He says that God’s sovereignty is “beautiful and comforting … being chosen relies not on our worthiness and merit … but on the hand of God and … his mercy” (Didymus: ibid.). Therefore, it is certain and cannot fail. It would seem that Bede also anticipates the later contentious issues of predetermination, when he indicates that it is a cooperative effort between us and God which brings about the reality of heaven: “No one by his own effort alone can become worthy of achieving eternal salvation by his own strength” ( Comm ., 72: ACC).

Читать дальше