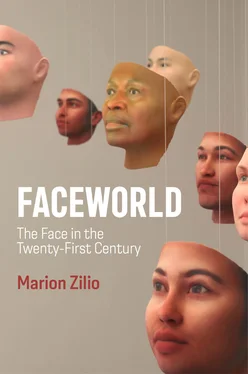

Facebook is a medium for people in their thirties, the medium of a generation that experienced the transition from analogue to digital, from the pre- to the post-Internet age with all of its personalized prostheses and their connected microphones and cameras. For ten years now it has served as a metaphor for the face’s new destiny – a face that is edited and published, eager to advertise and exhibit its intimacy. This everyday sociality may seem vulgar to our contemporaries, but in fact it lays the foundations for another reading of the face. The face may not just be a stimulus like any other, the metaphysical tradition may have seen it as the site of the encounter with the Other, and modern psychology may have postulated that it constitutes a primary form of interiority; but what has been forgotten is that individuals – that is to say, indivisibles – are only subjects in so far as they participate in a subjectivity that is shared, engaging with an exteriority that cannot be dismissed as merely secondary.

It is this exterior aspect, long consigned to the shadowy world of Platonic appearances or the depths of the unconscious, that constitutes the enigma of the face. Formerly the locus of an existential quest, in its contemporary form the face now seems more like a return of the repressed. The modern epoch exposed the face to its dark counterpart, reified and rendered banal by technical reproduction and exposure value. It became an inter-face, possessing the qualities of both interiority and exteriority, container and content, but also human and non-human. Modernity dreamt of a subject that observed, named, and possessed, but couldn’t accept the fact that this subject itself would become the object of that same ‘masterful panoptic egotism’. 3Humankind’s continuous observation of itself could not take place without inviting a third term into the equation: the technical milieu. What this revealed was the technogenetic dimension of the face – something which, in turn, would have repercussions for its ontogenesis.

We need only look back to see how, during the industrial epoch, photography’s large-scale process of exteriorization of the face forged an other memory of the face, one that was no longer biological but technical. While Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari warned that in any society what is essential is ‘to mark and to be marked’, 4the invention of the face as a technical object made it just one product among others, a living archive available to all. Once only seen when they were depicted in genre paintings or revealed fleetingly in the reflections of stagnant waters or at the bottom of a cooking pot, just a few decades later faces would be everywhere, all of the time.

1 1. ‘Investigating the Style of Self-Portraits (Selfies) in Five Cities across the World’, http://selfiecity.net.

2 2. André Gunthert, ‘La consécration du selfie’, Études photographiques 32 (Spring 2015), https://etudesphotographiques.revues.org/3529.

3 3. Peter Sloterdijk,Spheres 1: Bubbles Microspherology, translated by Wieland Hoban (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2011), 86.

4 4. Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, translated by Robert Hurley, Mark Seem, and Helen R. Lane (London and New York: Continuum, 2004), 112.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.