Many projects tend to involve interested people who collect information to achieve a particular scientific research goal or goals. ‘Most successful crowdsourcing projects are not about large anonymous masses of people. They are not about crowds. They are about inviting participation from interested and engaged members of the public’ (Owens 2019). In this way, these crowdsourcing activities can be viewed as ‘contributory citizen science’. However, as Eitzel et al. (2017) remark, ‘not all citizen science is crowdsourcing and not all crowdsourcing is citizen science, some authors are concerned that these two words may become synonymous …’.

A fundamental aspect of citizen science is that the research goal is defined by a particular person or group, with participants recruited through an open call providing some significant effort towards achieving that goal or goals. It describes the engagement of people in scientific processes who are not tied to institutions in that field of science. Citizen science projects can range from projects developed completely independently within individual volunteer initiatives, to collaborative transdisciplinary work, to formalised instructions and guidance provided by scientific facilities.

There are numerous projects and disaster learning activities that involve the scientific collection of data for research and emergency management purposes. The growth in more readily available and low-cost technologies – such as smartphones, social media, and the internet itself – is allowing disaster citizen science initiatives to grow rapidly. For example, in northeast England, a citizen science project has harvested and used quantitative and qualitative observations from the public in a novel way to effectively capture spatial and temporal river response (Starkey et al. 2017). According to these researchers, not only are these ‘community-derived datasets most valuable during local flash flood events, particularly towards peak discharge’, they assist in community risk awareness.

2.3.4 Community Participatory Disaster Risk Assessment

As part of disaster risk management, an understanding of the spatial dimensions of risk is required across vulnerability, exposure, and hazard, as well as the at-risk community's capacities (Keating et al. 2016). However, ‘a major gap still exists between what the models can provide and what local practitioners need; and there is a serious lack of appropriate local information on disaster impacts, as well as information on exposure and vulnerability, the latter of which is especially difficult to define, measure, and monitor’ (Liu et al. 2018).

Community participatory disaster risk assessment has been considered an effective way to collect disaster risk information. Major humanitarian and development organisations and agencies, such as the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, Oxfam, and CARE International, have used community-based participatory risk assessments to gather, organise, and analyse information on the locale-specific vulnerability and capacity of communities. There are numerous examples of communities participating in risk assessments through provision of their local knowledge.

Community mapping plays a key role in the participatory disaster risk-assessment process. Mapping helps stakeholders visually represent the bio-geophysical characteristics and various resources in a community. Additionally, according to Liu et al. (2018), it ‘is highly useful in stimulating discussions among community members’ and resultant disaster learning.

2.3.5 Volunteered Geographic Information

The sharing and mapping of spatial data through voluntary information gathered by the general public is termed ‘volunteered geographic information’ (VGI). Using VGI and participatory mapping prior to disasters can involve the identification of the potential impacts to a community and vulnerable groups, and thus ‘hot spots’ of risk. However, according to Haworth et al. (2018), ‘this process may motivate residents to improve their level of preparedness, but may also provoke feelings of shame, guilt, or resentment toward those involved in the mapping’.

According to Klonner et al. (2016), research so far has emphasised the role of VGI in disaster response. The presence of both researchers and volunteers is concentrated in response to crises, as opposed to during mitigation or preparedness activities, likely related to response being more visible and prominent, especially in the media (Haworth 2016).

The crisis map is a real-time gathering, display, and analysis of data (political, social, and environmental) during a crisis. Crisis mapping allows a large number of people to control, even at a distance, response actions by providing information to manage them. According to Meier (2011), ‘Crisis-mapping can be described as a combination of three components: information collection, visualization, and analysis. All of them are incorporated in a dynamic, interactive map.’

Specific apps, social media, participatory mapping tools, local language materials, and training programmes, as well as working closely with local partners, can help increase programme outreach and strengthen stakeholder engagement (Gunawan 2013).

A well-documented example of crisis mapping is the global volunteer mapping effort which assisted the humanitarian response to the 2010 Haiti earthquake (Meier 2012).

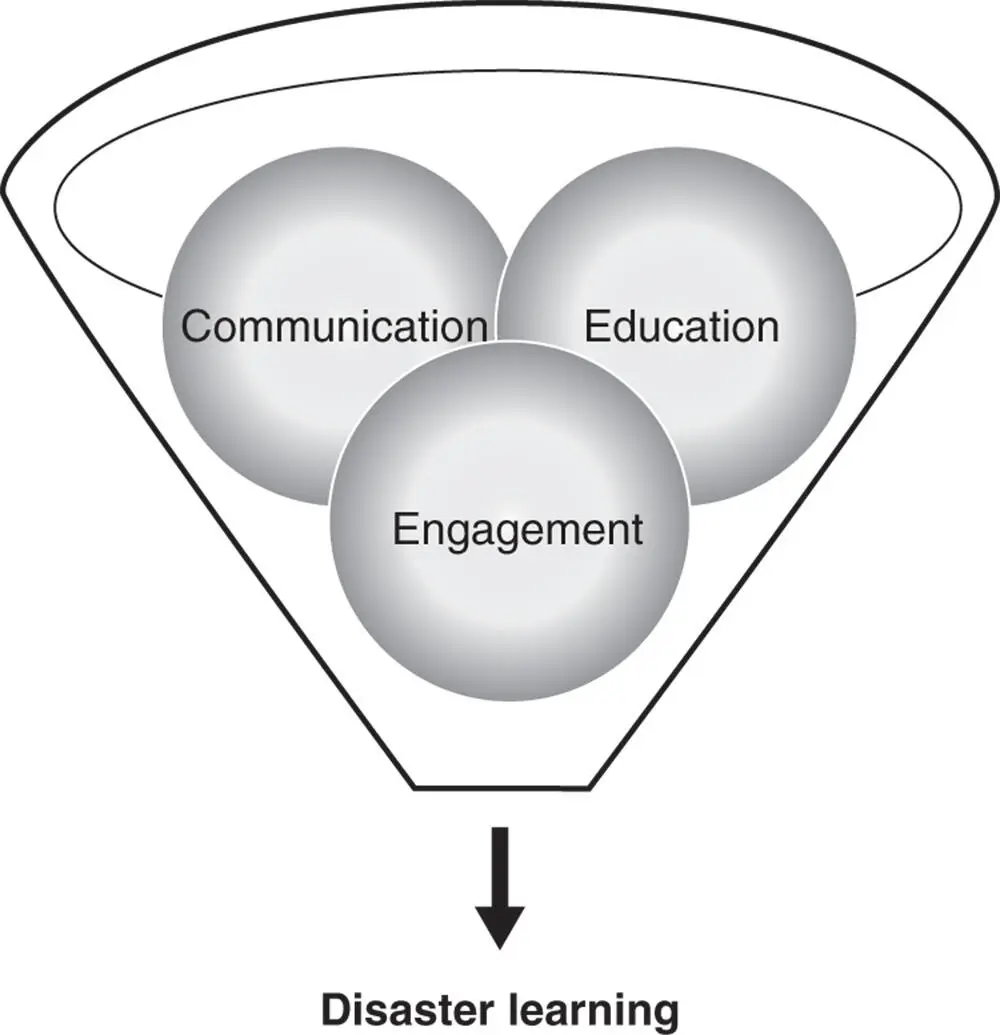

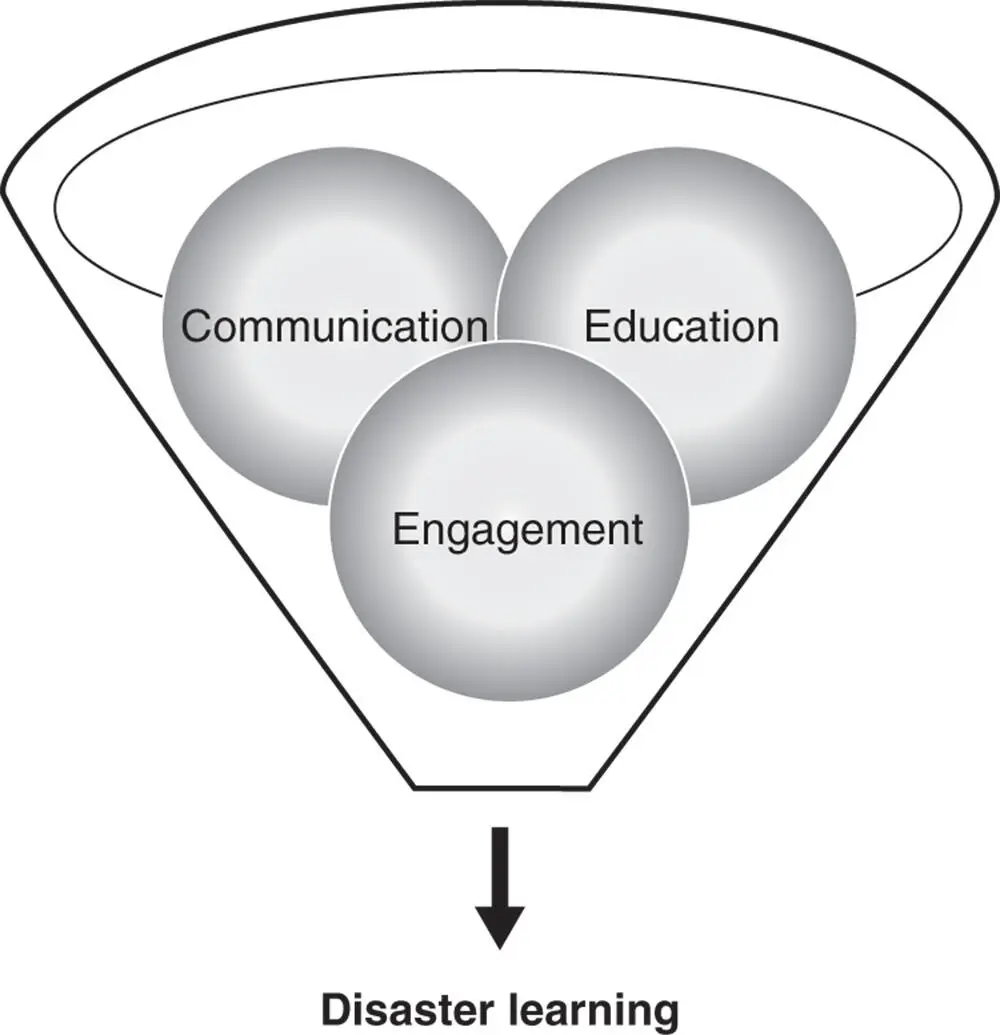

There is a tendency for emergency agencies and other emergency service organisations to divide disaster learning services into at least community ‘education’, ‘communication’, and ‘engagement’ (Dufty 2013). On the other hand, some agencies use one or some of these terms as all-encompassing titles for their disaster learning services.

The difficulty with the former approach is that there is the risk of a possible disjunct between the messaging and guidance to communities from different sections of the agency, e.g. those doing crisis communication and those doing preparedness education or engagement.

The difficulty with the latter approach is that by calling all community disaster learning one or two of the terms, the specific benefits of the term or terms excluded are not recognised and activated.

This book posits that an integrated Education, Communication, and Engagement (ECE) approach which names the three terms, and uses their independent but combined benefits, is more appropriate for emergency agencies and other emergency service organisations, such as humanitarian organisations. It follows from Dufty (2011) who argues that disaster education and engagement are both required as they provide ‘breadth’ and ‘depth’ to disaster learning. Figure 2.1graphically shows the Disaster ECE triumvirate that leads to effective disaster learning.

Table 2.1provides a harmonisation of the three types of community disaster learning described in this chapter. As identified in Table 2.1by bold type, there are some similarities between aspects of ECE. For example, there is similarity between ‘Inform’ as in the IAP2 Public Participation Spectrum (engagement), ‘one-way’ communication, and information-based informal and incidental education. However, as shown in Table 2.1, there are some outliers where there is no apparent harmonisation across the three types of community disaster learning; nevertheless, these should be included in Disaster ECE.

Figure 2.1 Disaster ECE leading to learning.

Table 2.1 Harmonisation of disaster education, communication, and engagement.

Читать дальше