Choosing a topic for study

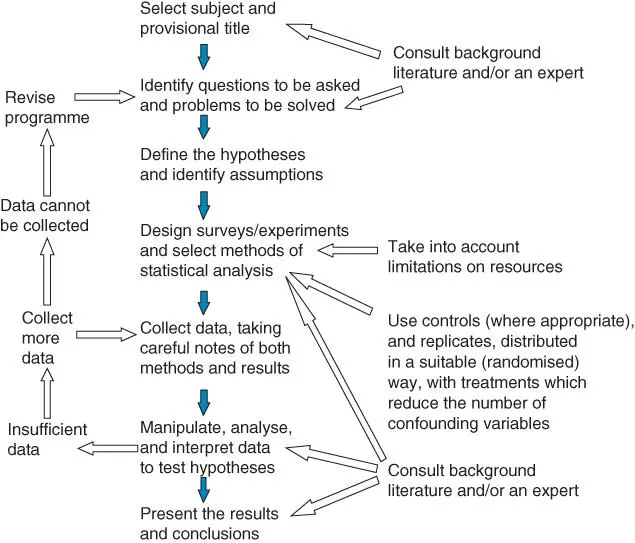

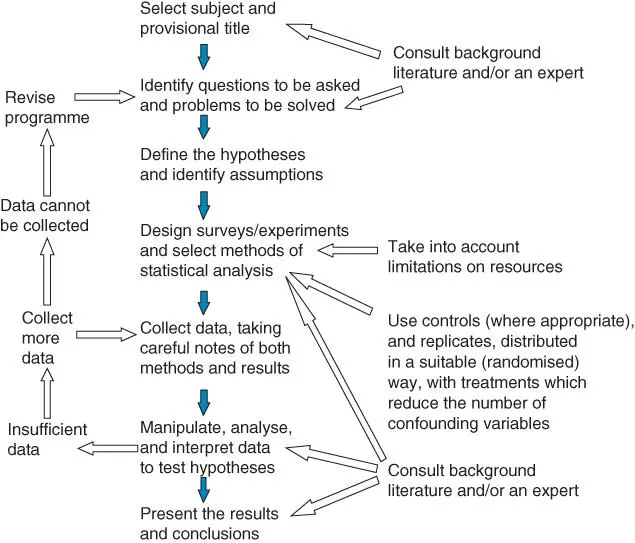

The first stage of a research project is choosing a subject area in which to research (see Box 1.1for a list of some texts that include ecological project ideas). As you will be devoting substantial time to your project, it is important to choose a topic that interests you. You may also wish to make your research relevant to your current or future employment. A variety of organisations – local, national, and international – may be able to help you identify an area of interest that is also of current relevance. Such organisations include local authorities and wildlife trusts, nature reserves, museums, and (inter)national bodies such as the RSPB, Plantlife, and WWF (Naturenet provides a list of some such organisations that may be able to help). 1 Pick a topic of the right size: neither too big nor too small – typically the fieldwork component of most undergraduate projects are less than 6 weeks in length. Looking at successful previous projects may assist you in judging how much can be done in the available time (ask more experienced researchers for examples of good projects to look at). Finally, your proposed project has to be feasible; for example, in terms of equipment, access to sites, and realistic timescales. Once you have selected your subject and provisional title, be prepared to be flexible and, if necessary, to change direction. This may happen for a variety of reasons; for example, if a pilot study reveals a more interesting avenue for research, or if your original ideas turn out to be unfeasible. You should note that the planning process should involve a consideration of the whole project to enable you to identify and deal with any potential problems before they become major issues (see Figure 1.1). In all aspects, reading around the subject will allow you to use appropriate techniques, build on existing knowledge, and avoid reinventing the wheel. Inevitably, there can be logistical problems that influence your choice of site, or species, or otherwise prevent you from proceeding exactly as you would have wished. Although you can avoid many such problems by careful planning, there are some aspects that you will not think about until you implement the research. A pilot study will help to identify such issues and may allow you to refine the study in advance of full implementation. If you are unable to do a pilot study, at least try to explain your approach to someone who has spent time doing ecological fieldwork. They may highlight some obvious deficiencies. This is particularly useful for field trips abroad, which preclude a pilot and can be fraught with difficulty.

Figure 1.1 Flowchart of the planning considerations for research projects.

Box 1.1 Some sources of ecology projects

There are a number of journal papers that list topics of interest in ecology and associated fields (e.g. Sutherland et al. 2006; Sutherland et al. 2009; Pretty et al. 2010; Sutherland et al. 2013). Even if the projects themselves are not of direct interest, they may inspire other project work since there is plenty of debate stemming from these papers on a variety of blogs and forums.

Natural England has a list of research ideas on their national nature reserves https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/research-opportunities-on-national-nature-reserves-in-england

There are many other resources that give examples of feasible ecological research projects. The series listed below are examples of some of those that cover either a wide range of habitat types, or a range of organisms.

The Practical Ecology Series provide project ideas associated with grasslands (Brodie 1985), freshwaters (Gee 1986), the seashore (Jenkins 1983), and urban areas (Smith 1984).

Routledge Habitat Guides each include a section (section 5) giving project ideas for the habitats associated with grasslands (Price 2003), uplands (Fielding and Howarth 1999), urban habitats (Wheater 1999), and woodlands (Read and Frater 1999).

The Biology of Habitats Series covers a wide range of global habitat types and includes practical aspects of working within the habitat and some of the types of studies that are possible within them (e.g. Rydin and Jeglum 2013 for peatlands and Little et al. 2009 for rocky shores).

The Naturalists' Handbook Series (now published by Pelagic Publishing) contains many ideas related to studying a group of species (e.g. Gilbert 2015 on hoverflies or Roy et al. 2013 on ladybirds), or different habitats (e.g. Hayward 2015 on sandy shores or Wheater and Read 1996 on animals under logs and stones), or implementing different techniques (e.g. Unwin and Corbet 1991 look at insects and microclimate, whilst Richardson 1992 examines pollution monitoring using lichens).

Ecological research questions

Having decided on a provisional topic, the next step in the successful planning of any research project is to identify those questions you wish to ask and then to formulate the aims and objectives. There are various reasons for researching particular plants, animals, or environments and this section provides a quick overview of the scope of ecological projects.

Many studies involve monitoring the number of species, number of individuals (relative abundance), estimates of population size or density (absolute abundance), or community structure (diversity, evenness, and richness). Additionally, studies on animals may require observations of the behaviour of individuals or groups and their interactions with each other and their environment.

Monitoring individual species and groups of species

Sometimes, projects may be targeted at a single species (i.e. an autecological study). For example, where a species is judged to be important for positive reasons (including its conservation or commercial value) you might require information about its distribution, population size and dynamics, age structure, behaviour, etc. Where there is a more negative view of a species (e.g. because it spreads disease, competes with native fauna and flora, or is an invasive species that dominates a habitat to the exclusion of other species), you may need information about its distribution, dispersal ability, vulnerability to disturbance and predation, etc. A biogeographical study that might be of interest is the examination of species' distributions where species are expanding or contracting their ranges – perhaps as a result of climate change or other factors (either natural or human‐influenced, e.g. habitat disturbance and fragmentation). Conversely, you may be interested in groups of organisms (i.e. community ecology or synecology), examining the diversity of communities, the interrelationships between plants and animals in protected areas, or in establishing ecosystem function in relation to environmental legislation (e.g. the EU Water Framework Directive). 2 Studies spanning a wide range of different taxa can be particularly valuable in understanding complex environmental systems, although they may be difficult to implement and the subsequent analysis and interpretation of the results can be complicated.

Monitoring species richness

In studies examining species richness, you might be interested in the presence or absence of one or more species (or other taxonomic group) in order to investigate the links between such species and aspects of the environment; for example, in terms of the ecology of the species concerned, or in studies of pollution where the species may be useful as a biological indicator of certain toxins. Here, simply listing the plants and animals present may suffice. Although this may appear to be a quite simple approach, care needs to be taken to ensure that sampling techniques are used that are appropriate to both the organisms under consideration and the habitats in which they are found. For example, studies on bird species richness in urban parks may be complicated if some parks are dominated by relatively open habitats of amenity grassland and formal flower gardens, whilst others feature dense shrubberies and even woodland. Observations of the species present may be easier in the open habitats than under dense canopy. Care will thus be needed to ensure that all species are counted (as accurately as possible) using the most appropriate method for that site or habitat type. For these reasons, issues around surveying habitats and sampling organisms are considered in the next three chapters.

Читать дальше