Goal‐Setting Theory and Objective‐Setting Practice

Peter Drucker popularized the importance of setting goals and objectives in his classic book, The Practice of Management , published in 1954. While there is still some question about who first used the term management by objectives (MBO), it is generally conceded that the initial push came from Drucker, who attributes it to Alfred P. Sloan, the managerial and organizational genius who is credited with building up General Motors.

In the 1960s, Edwin A. Locke published a series of articles that detailed his research on goal setting and on how these motivate people. He not only explained why goals work but also proposed some basic rules for setting them. While Drucker, Locke, and most other goal‐setting theorists put their work in a managerial context, these theories also apply to individual goal setting where competence and confidence grow as you get better at your own objectives and goals.

Goals and objectives have a significant effect on performance if they have the following attributes: clarity, difficulty, and feedback. A goal has a time horizon of more than one year and an objective has a time horizon of less than a year. Therefore, one would set several short‐term objectives to reach a long‐term goal.

Clarity is the single most important element in setting goals. Goals and objectives must be specific so they can be measured. A general objective of increasing the number of prospecting calls next month is vague, nonspecific, and virtually useless. A more specific objective would be to average two prospecting appointments per day for the next month.

Increasing the difficulty of goals and objectives generally amplifies the challenge, which, in turn, raises the effort to meet the challenge. This concept of goal difficulty creates confusion and is where defining the difference between goals and objectives becomes important. Because goals have a long‐term time horizon, it is useful to set goals, and, thus, expectations, high. In the best‐selling book, Built to Last , Collins and Porras’s research shows that one of the things that highly successful companies have in common is that they set BHAGs – Big, Hairy, Audacious Goals. The authors write: “A BHAG should be so clear and compelling that it requires little or no explanation. Remember, a BHAG is a goal – such as climbing a mountain or going to the moon – not a ‘statement.’ If it does not get people juices going it is just not a BHAG.” 24 One of the 18 built‐to‐last companies was Merck. Its BHAG was “to become the preeminent drug maker worldwide, via massive R&D and new products that cure disease.” 25

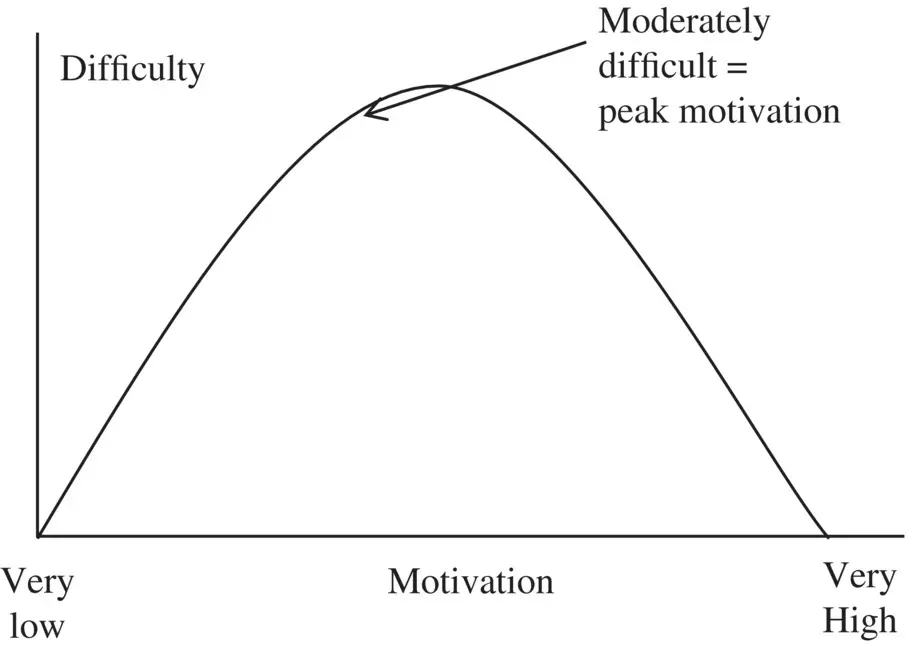

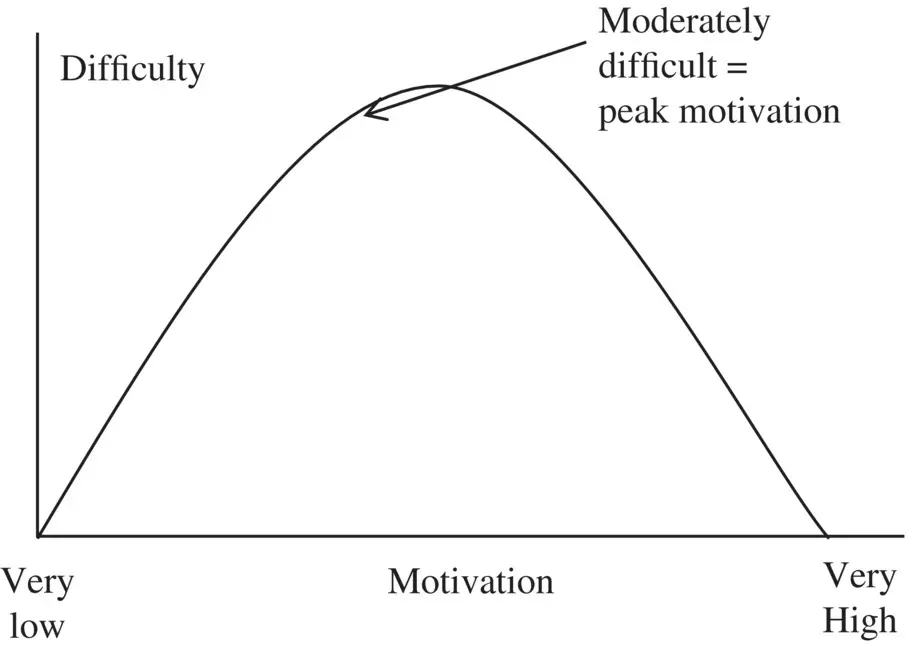

On the other hand, short‐term objectives set by salespeople and their management should be set to make people feel like winners, a deep‐seated need. Unfortunately, management often set BHAGs, or “stretch,” short‐term objectives, believing that they motivate people. Figure 4.1shows the relationship between motivation and objective difficulty. Setting a very low objective has no motivating effect. On the other hand, setting an objective too high demotivates people because they give up the moment they realize that the objective is unachievable. Working hard to achieve an impossible objective creates cognitive dissonance, so people quit making an effort in order to bring thinking and action into internal harmony.

As you can see from Figure 4.1, the best objectives are moderately difficult, yet provide a challenge because they are perceived as attainable and are, thus, motivating. Contrary to what many managers believe, the trick in setting objectives is to set them on the low side of the moderately difficult peak to ensure that they can be reached with a strong effort and, thus, allow people to feel successful. Unfortunately, too often managers set objectives on the high side of the moderately difficult peak and, thus, unintentionally reduce people’s motivation. It is better, in fact, to be a little on the low side than to be a little on the high side because you want to make sure that the salespeople feel like winners.

Figure 4.1 Objective difficulty and motivation

Interestingly, people with low self‐esteem often set unrealistically high goals because they expect failure. Already viewing themselves as losers, they are more comfortable reinforcing this view in advance. Claiming that “the objective was too high,” allows them to quit before trying rather than attempting something difficult that they think they are bound to fail at.

The ideal is to set a series of moderately difficult, challenging objectives that get progressively more difficult and challenging as each objective is achieved (a critical element in deliberate practice). This series of realistic step‐by‐step, increasingly more difficult objectives will eventually lead you to your BHAG.

In 2018 in his annual letter to stockholders, Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos related a story that reinforced the importance of setting realistic goals. The title of his anecdote was “Perfect handstands,” and read: “A close friend recently decided to learn to do a perfect free‐standing handstand… In the very first lesson, the coach gave her some wonderful advice. … ‘The reality is that it takes about six months of daily practice. If you think you should be able to do it in two weeks, you’re just going to end up quitting.’ Unrealistic beliefs…kill high standards.” 26

Setting objectives and goals that achieve high standards is an art. Achieving high standards takes work, analysis, thought, and incredible persistence when faced with an unpredictable future.

You need to get feedback – a reading on how you are doing. You receive feedback from yourself by successfully solving problems and closing sales, by analyzing what you did right, or by failing and analyzing what you did wrong. For example, analyzing statistics about your ratio of total calls to successful calls will give you feedback on how you are doing. Furthermore, you should get feedback on your objectives and goals from your manager on a regular basis. You have the right to know how you are doing and what your manager thinks you can do to improve.

Objective‐setting practice

Sound individual objectives must be:

1 Measurable

2 Attainable

3 Demanding

4 Consistent with company goals

5 Under the control of the individual

6 Deadlined

Here is a mnemonic for setting objectives – MADCUD. I will provide you with more details about using and prioritizing the MADCUD objectives on a daily and weekly basis in Chapter 25: Time Management. But for now, here are the elements’ definitions:

The measurable criterion relates to the concept of clarity. Objectives and goals must be specific enough to be measurable, for example, “to increase sales by 15 percent” or “to increase your number of face‐to‐face presentations from a current average of 10 per week to an average of 15 per week.” Notice that objectives always begin with “to,” which implies an action you are going to take.

Setting specific, measurable, revenue objectives is not necessarily a good idea, although it is common practice. Rather than setting the final objective as a revenue objective, it is more productive to set a series of specific, measurable, smaller objectives that will help you reach a desired monthly revenue level. In the chapter “A bias for action” in In Search of Excellence , Thomas J. Peters and Robert H. Waterman, Jr. quote the president of one successful company who says he has his managers focus on a few important activity‐based objectives. If they have this task‐oriented focus, he says that “the financials will take care of themselves.” 27

Читать дальше