S. Jane Flint - Principles of Virology, Volume 2

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «S. Jane Flint - Principles of Virology, Volume 2» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Principles of Virology, Volume 2

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Principles of Virology, Volume 2: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Principles of Virology, Volume 2»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Volume I: Molecular Biology

Volume II: Pathogenesis and Control

Principles of Virology, Fifth Edition

Principles of Virology, Volume 2 — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Principles of Virology, Volume 2», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Focus on Frontline Health Care: Ebolavirus in Africa

In December 2013, a one-year-old boy in Guinea died from complications of Ebola virus: he was the first victim of what would become an epidemic that claimed over 11,000 lives and lasted more than two years. During this period, the virus spread to the neighboring countries of Liberia and Sierra Leone, and it is conservatively estimated that more than 28,000 individuals became infected from December 2013 to late 2016. The epidemic was fueled, in part, by poverty, social unrest, armed conflict, and inadequate or absent health care systems. Furthermore, local burial customs, including ritual washing of the corpse, facilitated person-to-person transmission. Air transportation of infected persons out of these areas caused infections in health care workers, including in hospitals in Spain and the United States. While these latter cases did not spread further, the entry of this highly lethal virus into these countries created widespread public anxiety in these countries. Such anxiety likely contributed to greater awareness of the devastation that was in progress on the west coast of Africa.

Ebola virus is probably transmitted by bats, and, indeed, the index patient’s village was located near a large bat colony. Ebola virus is spread by direct contact with body fluids: mucus, saliva, blood, and, as determined later, semen. Ebola hemorrhagic fever, which typically starts with high fever, headache, and muscle pain, often progresses to vomiting, diarrhea, and rash, and eventually kidney and liver impairment. In some infected individuals, rupture of infected blood vessels leads to internal and external bleeding (hence the name hemorrhagic fever), which can cause death from low blood pressure and fluid loss. The disease carries an extremely high risk of death, killing between 25 and 90% of those infected, although the odds of survival are directly dependent on the efficiency and quality of health care: providing fluids (saline, blood transfusions) greatly increases an infected individual’s chances of survival.

More than any epidemic in recent memory, media attention was particularly focused on the health care workers on site, who provided care for the victims and potential victims ( Fig. 1.7). The Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders), which received the 1999 Nobel Peace Prize for its work throughout the developing world, provided much of this frontline care. In late 2014, at the peak of the epidemic, physicians and support personnel were exhausted, hospitals had little room for new patients, and lack of adequate resources forced heartbreaking choices on those doctors: provide optimal care to a few or substandard care to many. To care for the victims, medical personnel put themselves in extreme danger: despite protective gear, approximately 10% of Ebola virus fatalities occurred in health care workers. Lack of running water, oppressive temperatures, and outdated sup plies were all likely contributors.

Eventually, border closings, mandatory quarantines, and public education that led to changes in burial practices slowed the spread of the epidemic. In December 2016, the WHO announced, after a two-year trial, that a recombinant vaccine appeared to offer protection from the Zaire strain of Ebola responsible for the West Africa outbreak ( Chapters 7and 9).

Figure 1.7 Ebola outbreak. Health care workers in areas of the Ebola virus outbreak are completely protected from any contact with body fluids from a potentially infected individual. Standard safety protection includes a suit, apron, boots, gowns, gloves, masks, and goggles. One physician working in Sierra Leone stated: “After about 30 or 40 minutes, your goggles have fogged up; your socks are completely drenched in sweat. You’re just walking in water in your boots. And at that point, you have to exit for your own safety … Here it takes 20–25 minutes to take off a protective suit and must be done with two trained supervisors who watch every step in a military manner to ensure no mistakes are made, because a slip up can easily occur and of course can be fatal.” AP Photo/ Jerome Delay, File 288676002851.

Though the impact of the virus abated, epidemics have long-lasting economic ramifications: it has been estimated that the financial toll of this epidemic exceeded $1.6 billion, accelerating poverty, which, as estimated by one news organization, likely caused as many deaths as the outbreak itself.

Emergence of a Birth Defect Associated with Infection: Zika Virus in Brazil

As the Ebola outbreak was resolving in Africa in 2015, a new viral epidemic was beginning in South America. The first confirmed case of Zika virus infection in the Americas was reported in northeast Brazil in May 2015, although phylogenetic studies indicated that the virus had been introduced as early as 2013.

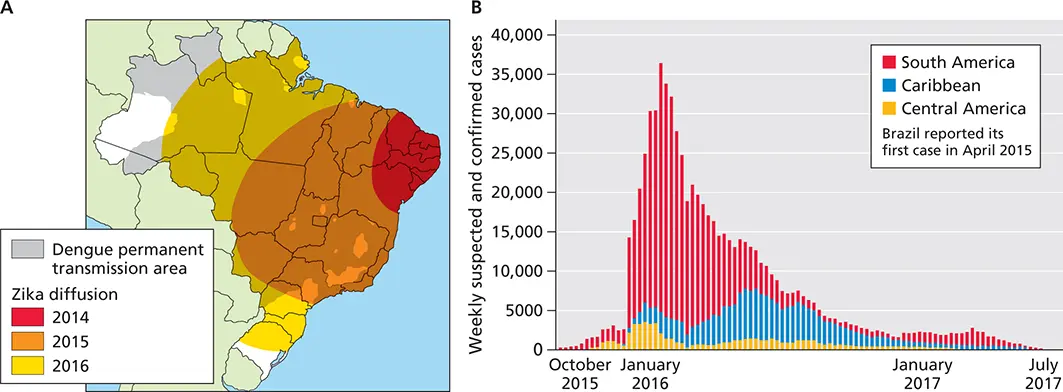

Zika virus is transmitted by mosquitos in temperate climates and causes a relatively mild disease in most cases: many adults seroconvert without ever knowing they were infected. However, during the 2015 outbreak it was rapidly appreciated that Zika virus infection of pregnant women can be associated with a terrifying new symptom in their newborns: small, misshapen heads (microcephaly) and severe developmental defects. As the virus spread throughout Brazil and beyond ( Fig. 1.8), people in Mexico and North America quickly realized that the geographic range for the mosquito vector, Aedesaegypti , extended well into these areas. The rest of the Americas awaited the summer months braced for disaster, as mosquitos were predicted to carry Zika virus inexorably north. The outbreak coincided with the Summer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro, and prompted many enthusiastic supporters and athletes to stay home. For reasons still unclear, these fears did not materialize. By 2017, most of Latin America and the Caribbean had a massive decline in Zika virus infections. It has been suggested that the sharp reduction in cases is due, at least in part, to a phenomenon known as herd immunity( Chapter 7). Virus transmission between humans and mosquitos is greatly reduced in a population when enough people become immune to a virus, through vaccination or, as in the case of the Zika virus, natural immunity following infection.

Figure 1.8 Zika spread in Brazil. (A)In three short years, from 2014 to 2016, Zika virus moved progressively north and westward, spreading from the coastal region of Brazil to other countries in South America. (B)Decline of Zika virus cases since 2016. Adapted from Lowe R et al. 2018. Int J Environ Res Public Health 15:E96, under license CC BY 4.0.

Epidemiology

The stories above highlight some of the unique challenges, uncertainty, and urgency that face epidemiologists during an outbreak. The study of viruses can be likened to a set of con centric circles. The center comprises detailed analyses at the molecular level of the genome and the structures of viral particles and proteins that are crucial to understanding viral re production, and the biochemical consequences of interactions of viral and host cell proteins. How infection of individual cells affects the tissue in which the infected cells reside, and how that impacted tissue disturbs the biology of the host, de fine the landscape of the field of viral pathogenesis, in the next level (discussed in the following four chapters). But if a viral population is to survive, transmission must occur from an infected host to susceptible, uninfected ones. The study of infections of populations is the discipline of epidemiology, the cornerstone of public health research and response. Within this broad, outer circle, major areas of epidemiological research include outbreak investigation, disease transmission, surveillance, screening, biomonitoring, and public education.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Principles of Virology, Volume 2»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Principles of Virology, Volume 2» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Principles of Virology, Volume 2» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.