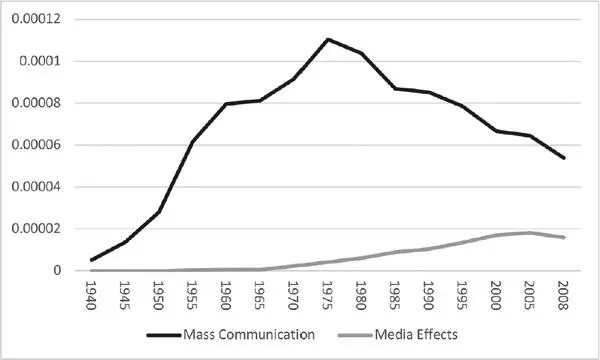

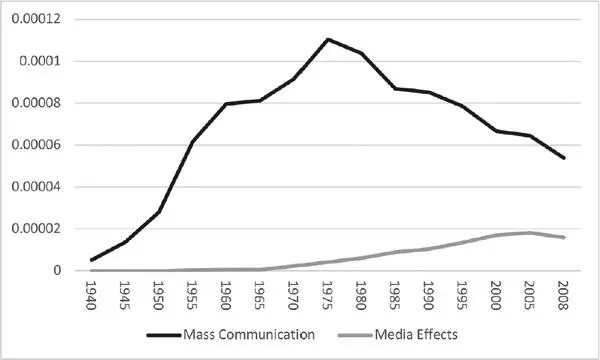

Figure 1 Appearance of the terms “mass communication” and “media effects” in books in English (as a % of total)

Source : Google Ngrams, https://books.google.com/ngrams

Some commentators have equated the overall field of communication with the quantitative study of media effects, though this is an obvious exaggeration. The growth in the number of studies focusing on media effects (and calling themselves that) was astronomical from the 1940s onward. Particularly as institutes were set up within universities to study communication, and then departments as well, media effects work acquired the qualities of being focused on determining measurable changes in attitude or behavior from exposure to media messages.

It’s impossible to pin down the absolute genesis of the idea of media effects, as there are plenty of references in the literature that use the terms “effects” before World War II, and also, as we have seen, some of the earliest studies attempted to assess effects from media. But the twin-birth of ideas about mass communication and media effects in the 1940s seems as good a place as any to set mile marker zero for the long highway of studies that were to come.

The foregoing material describes only one story about how people have studied media effects. While it is easy to over-generalize, much of the work described above looks at media from a perspective that can be termed “informational.” That is, media messages are usually seen as pieces or streams of information that can be absorbed by recipients. The questions of Lasswell lend themselves quite easily to this outlook; the methods of social science like to be able to boil things down to single quantifiable variables. Across hundreds and even thousands of studies, the goal of this kind of media effects research (even today) is to determine to what degree these absorptions are effective. Media effects has been, in many ways, a vast elaboration of the basic ideas of persuasion research. We will be examining this perspective in greater detail in later chapters.

Distinguished from this, there are approaches that look at media effects from an ideological perspective. These “critical” approaches have identified media institutions as the arm of an economic, political, and cultural order that describes and enforces norms in a world where power means everything. In these types of studies, effects are seen as emerging from the explicit or implicit encoding of ideological perspectives, outlooks, assumptions, and worldviews into messages, which then become the dominant way of looking at the world for media audiences. These approaches from media studies or cultural studies often use the term “effects” pejoratively. There has been a consistent tendency to denigrate effects research as an overly simplistic quantification that ultimately can’t prove its own point. However, even while abjuring the term effects , these scholars and thinkers have consistently put forward views of the media as quite powerful. Although they did not seek to make empirical demonstrations of their hypotheses through social science methods, their views were quite influential, either as a tocsin or call to arms about the need to understand media’s critical role, or as a counterpoint or whipping boy to the ideas of the informational theorists.

Ideological strains of thinking about media begin with reactions to Marx. To simplify greatly, Marxism – which itself adopted the mantle of science – had predicted that proletarian revolutions would come as workers would realize the injustice of the inequality of their situation in relation to capital. Although some of these revolutions did occur, first and most notably in Russia, they were not as widespread as would have been necessary to confirm the hypotheses of Marxism. From this came the work of follow-on theorists, many on the European left, who sought ways to extend the basic ideas of Marxism in light of the actual progression of history. Oftentimes this involved a view of the media as a sort of narcotic that distracts people from true class consciousness. If people were not reacting in ways that Marxist social theory predicted, it might have been because media served as a cultural “opiate” (Marx had also identified religion as such an opiate, and modern mass media was beginning to take on some of the trappings of religion as well).

Early proponents of this view were from the so-called Frankfurt School, who first brought European ideas about media and culture into contact with American perspectives in the World War II period. Their work was, and has continued to be, highly influential. The role of media in these analyses is as a corrupting force that dilutes genuine cultural expression and makes it into something more suitable for a culture “industry.” The powers (the “effects”) of this industry are assumed from the start, and are quite massive when compared to the effects that were studied by the social scientists. Major early figures in the Frankfurt School movement were Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer, who argued:

Films, radio and magazines make up a system which is uniform as a whole and in every part. Even the aesthetic activities of political opposites are one in their enthusiastic obedience to the rhythm of the iron system. The decorative industrial management buildings and exhibition centers in authoritarian countries are much the same as anywhere else. The huge gleaming towers that shoot up everywhere are outward signs of the ingenious planning of international concerns, toward which the unleashed entrepreneurial system (whose monuments are a mass of gloomy houses and business premises in grimy, spiritless cities) was already hastening. (Adorno & Horkheimer, 2002; During, 1993, p. 32)

Media is just another standardized product in the output of bourgeois capitalism, and serves the same functions and needs (Kellner, 1989). A related idea, that of cultural “hegemony,” was also offered. Theorists such as Gramsci (1971) noted that cultural production, dominated by ruling classes, is suited to and creates acceptance of the status quo. Cultural institutions can work through ideology rather than through more forceful means to engineer acceptance. Again, the view here is tied to a very strong media effects position. Media have the ideological power to manufacture consent to the dominant worldview.

How are these ideas related to media effects research? First, early critical theorists were often in contact with and even collaborating with some of the empirical researchers. They sometimes defined themselves in relation to each other. Critical theorists viewed those doing effects research as starting from assumptions that were tied to the dominant economic and social paradigm. They were seen as functionaries of a media system doing “administrative” tasks designed to further the effectiveness of the system (for a recent discussion, see Katz & Katz, 2016). The critics often asserted that the focus on effects was itself misguided, and positioned themselves as involved in a higher-level philosophical endeavor. So we often tend to see critical theorists as opposed to a strong view of media effects. But that view can be misleading:

There is a major flaw in thinking that administrative research is focused on effect, while critical research is not. It is true that administrative research looks at the causal chain of “who says what to whom with what effect.” But the effect is short run. But it is altogether wrong to overlook the giant effects [emphasis added] aimed for by the Frankfurt School – the production of consciousness, false and true, and ultimately on society. More than that, the ostensible reluctance of the Frankfurters to use the term effect is itself a giant statement that society continues at an uninterruptable standstill, and that the media serve to reinforce the status quo. In other words, “no change” is their major effect. (Katz & Katz, 2016, p. 9)

Читать дальше