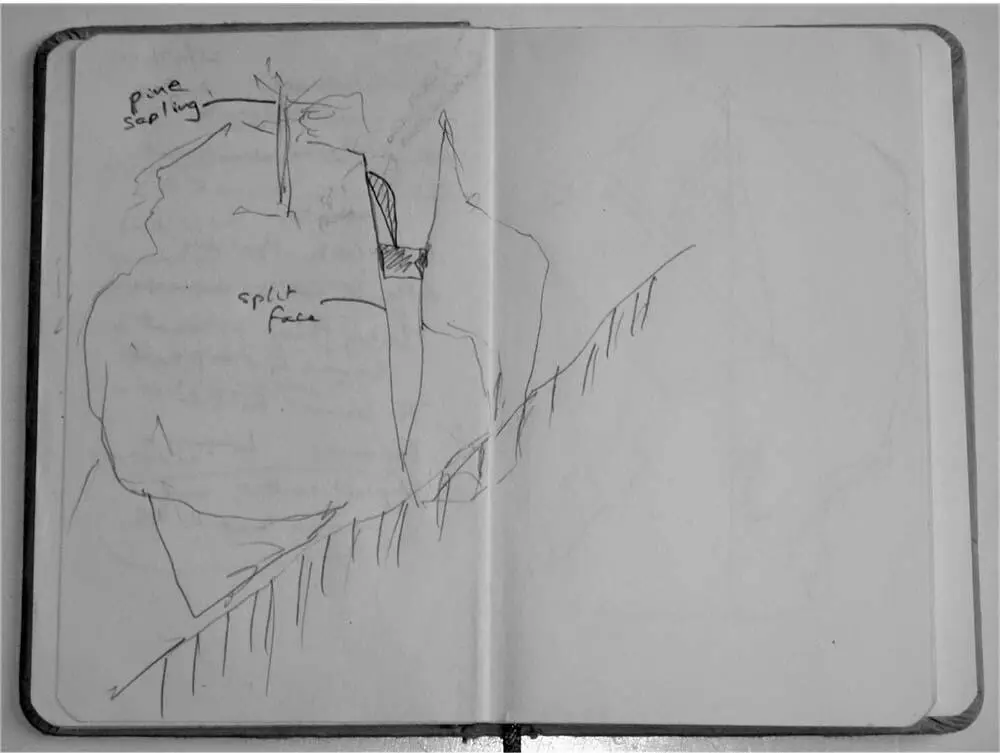

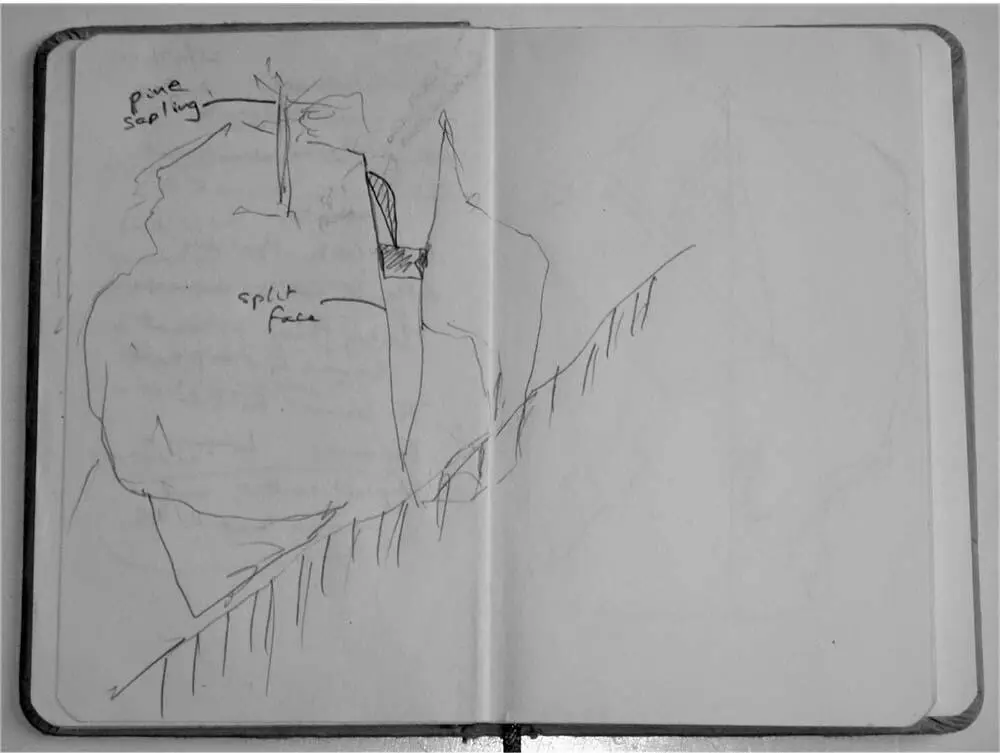

Figure 1 The boulder: a page from my sketchbook. (Photo by the author.)

Somewhere in these woods is a special tree. It is not large, nor has it grown to any great height. At its foot, its roots are tightly wrapped around an outcrop of glacier-smoothed rock, from which a thick, gnarled trunk coils out like a snake, eventually inclining towards the vertical as it thins into more recent growth, dissolving into a spray of needle-covered branches and twigs. The tree is a pine, and thanks to its location on the shore of a great lake, it has known extremes of wind and cold from which its larger inland cousins are somewhat protected. Its twisted trunk bears witness to early years of struggle against the elements, when once it was but a young and slender sapling. Deep inside, that sapling is still there, buried beneath decades of further growth and accretion. Now hardened and gnarled with age, my tree can hold out against anything that nature might throw at it. What for me is so special about this tree, however, is the way it seems to establish a sort of conversation between rock and air. At base the wood has all but turned to stone. The roots, following the contours of the outcrop and penetrating its crevasses, hold the rock in an iron grip. But up above, delicate needles vibrate to the merest puff of wind and play host to tiny geometrid caterpillars that measure out the twigs in their peculiar looping gait. How is it possible for such ageless solidity and ephemeral volatility to be brought into unison? This is the miracle of my tree. Through it, the rock opens up to meet the sky, while the annual passage of seasons nestles within what seems like an eternity. To spend time with this tree, as I have done, is at once to be of the moment and to sink back into a reverie of agelessness.

Here in these woods, forest ants are at work, building their nest. From a distance the nest reveals itself as a perfectly formed mound, circular in plan and bell-shaped in elevation. Observe it closely, however, and it turns out to be seething with movement as legions of ants jostle with one another and with the materials they have brought back – mostly grains of sand and pine-needles. From the centre, antroads fan out in all directions. You have to peer at the ground to see them. Often they are more like tunnels, boring their way through the dense carpet of mosses and lichens that covers the earth. If you were the size of an ant, the challenges of the passage would be formidable, as what to us are mere pebbles would present precipitous climbs and vertical drops, while tree-roots would be mountain ranges. Yet nothing seems to deter the traffic as thousands upon thousands of ants march out and back, the outward goers often colliding with returnees laden with materials of some sort to add to the heap. Wandering alone in the forest, it is odd to think that beneath one’s feet are miniature insect imperia, populated by millions, of unimaginable strangeness and complexity.

In the woods the wind is blowing. You can hear it coming from a long way off, especially through the aspen trees. Each tree hands it on to the next until, for a moment, their leaves are all singing to the same tune. Every leaf is aquiver, even though the trunks sway only a little. Then all is quiet again. The gust has moved on. On the waters of the lake the surface is disturbed into ripples which focus the reflected light into little suns that flash first double and then single. As the ripples reach the lakeshore, the reeds bend over, rustling in unison, until they in turn fall silent. Do trees create the gust of wind by waving their leaf-draped limbs? Does water create wind by rippling? Do reeds create wind by rustling? Of course not! Yet, surely, the clarinettist needs a reed to turn his breath into music. So if, by wind, we mean its music to our ears, or its sun-dance to our eyes, then yes – leaves, ripples and reeds do make the wind. For when I say I hear the wind, or see it in the surface of the lake, the sounds I hear are made by leaves just as much as is the light I see made by ripples.

Once I was flying a kite out on the field, where the grass had recently been cut. As I played on the string, it seemed to me that my kite, like the leaves of the trees, was also an instrument for turning aerial gusts into music in motion. However, the string, often entangled on previous flights, had been repaired at many points by cutting and retying. An unusually strong gust overwhelmed one of the knots and my kite broke loose. Off it went, sailing over the tree-tops, buoyed up by the wind. I imagine the kite having relished its new-found freedom. ‘Watch me,’ it would have crowed. ‘I am a creature of the sky. Field and forest, they are all the same to me!’ But its dreams were to come to an ignominious end as it drifted down to earth. Most likely it was snagged on an angling tree-branch as it fell. I never found it again. But I am sure it is there, somewhere in the woods, draped forlornly from the branch, utterly lost.

I too, in straying from field to forest, have risked becoming lost. I know an old path that runs through the woods, though I am not sure where it begins, and it ends in the middle of nowhere. Long ago, however, it was made by the passage of many feet as people, year in year out, would go with rakes, scythes and pitchforks from the farms around the lake to cut the hay in far-flung meadows. The hay would be stored in field-barns and brought in by horse and sledge over the winter to feed the cattle in their stalls. But that was in the past. First the horses went, as every farm acquired a tractor. Then the outfields were abandoned, as forestry became more profitable than dairy production. Then the cows were sold off, and finally the people left. Few farms remain inhabited year-round. And so the path fell out of use and is gradually fading. In places it has completely disappeared. Trees have fallen across it or are even growing in its midst. I can tell the path is there only by following a line of subtle variation in the leaf-mould on the ground, a gap in lichen cover, a thinning of soil on rock. So long as I am on it, I can discern the path by running my eye along the line. But I know that if I move to one side or the other, the line will disappear. Indeed this has happened to me on more than one occasion: having deviated from the path in one direction – my attention drawn by an anthill or by luscious bilberries to pick – I have crossed right over it on the return without even noticing, and strayed too far in the opposite direction. How, then, should we think of this path, which is visible only as you go along it? It is a line made by walking; an inscription of human activity on the land. Yet while one can distinguish the path from the ground in which it is inscribed – albeit only faintly and with an eye already tuned to its presence – it is not possible to distinguish the ground from the path. For the ground is not a base upon which every feature is mounted like scenery on a stage set. It is rather a surface that is multiply folded and crumpled. The path is like a fold in the ground.

Somewhere in Northern Karelia there are still cows. But here there are none. The fields fell silent many years ago. Once we would row across the lake with a churn to fetch milk, warm and fresh, from the dairy. But these days, it doesn’t pay to look after a few head of cattle, and anyway, who will do the milking when the old folk retire? No girl wants to follow her mother into the cowshed; no boy aspires to what has always been seen as women’s work. Nowadays cattle are concentrated in big production facilities, whose managers rent the fields once used for grazing to provide a year-round supply of fodder. Sometimes I imagine that the cows are still there, wandering the fields like ghosts. I think I see them staring asquint with their doleful moon-eyes, and hear them lowing, chewing the cud, crashing through undergrowth. Then silence falls again, pierced only by the wistful cry of the curlew. Where the cows once lingered, strange white oval forms can be seen scattered here and there over the meadows, or lined up on their trackside perimeters. People call them ‘dinosaur eggs’. Really, they are gigantic rolls of machine-cut hay. The machine rolls the hay as it cuts, and as each roll is completed, it is automatically wrapped in white plastic sheeting and laid – like a great egg – on the ground. Later, the ‘eggs’ will be collected and taken far away, to the place where all the cows are now.

Читать дальше