1 ...8 9 10 12 13 14 ...20 ‘Don’t,’ is his answer; a full stop that ends a conversation that never began, and then there is no sound except the scraping of cutlery on plates.

I listen to the interview in the dark, in bed, with an earphone in my left ear, my head sinking into the pillow. The cotton releases the smell of Mim’s lavender-scented washing conditioner. It is a smell of safety. My whole body calls this bed mine but it is Simon’s and Mim’s spare bed, for guests, not a permanent place for me.

I have no home.

Nowhere that I can call mine. I think it makes it worse that the only place I have ever thought of as mine is now Dan’s and his new woman’s. But I couldn’t be the one who kept the flat because I was too ill to live in it alone.

If I’d had parents, I would have had a home to always go back to. A home like Louise’s, with a flower bed full of scented roses, and parents who loved her. There’s that vacuum again.

The emotion in me is envy. It is my emotion. Louise had what I always wanted.

When the vacuum sucks everything away this is what’s left: darkness. Envy. Anger. Pain. These are the emotions that can take over when bipolar slips into what people call manic depression.

The Dowlings’ radio interview is eleven minutes long. They talk for four minutes then there is a break for a song and another seven minutes.

I want to help. I wish I had something I could say that would help. Their love for Louise flows in the cadence of their voices. There is a moment when Robert says something to his wife, Patricia. ‘ I know, Pat, I feel that way too. ’ I imagine him holding her hand as she makes a sound, a slight acknowledgement that says she is reassured.

An ache presses through my heart, as it makes itself heard, in a gentle rhythm as I listen to the Dowlings again.

Louise’s sadness becomes a lead weight in my chest and there’s a tension in my throat; she wants to cry.

If I were her, I would be crying.

I want to know love like that.

In Louise’s body, while she was alive, I think this heart would have clasped tight with love when she heard these voices.

The Dowlings mean everything to one another and Louise must have been enveloped in that love too.

When I was young, I imagined myself in a happy sitcom family. But Louise’s family are painting a new mental picture of what life would have been like with parents. What her life was like. What mine could have been like – still might be like.

I look up the one image of Louise that I have access to and play the recording from the beginning, listening for her voice inside me. I can’t hear the words but I hear her: a whisper that’s out of reach.

I want to hear her. I want to understand what she’s saying. I want to understand what she wants me to do.

Chapter 10

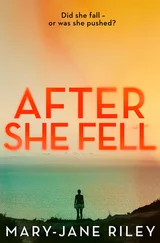

6 weeks and 1 day after the fall.

When I leave the railway station, a strong breeze sweeps at me like a broom trying to push me back through the sliding doors.

An answering shiver rattles through my body, up my spine and into my shoulders.

When I dressed this morning, I chose a thin jumper, not thick enough to keep out the cold. I haven’t mastered the forecasting skills required for being outside in the British weather, and the chill in the air is a reminder that in just over two weeks it will officially be autumn.

But perhaps the shiver came from the sense I have that Louise is watching me walking the streets of Swindon – a someone-has-just-walked-over-my-grave sort of shiver.

Her spirit feels more active today. Louder. My heart is pulsing hard and there is a hum of energy in my blood that is making her undeterminable whispers stronger. It is like having someone fidgeting impatiently in my body.

The crossing that is in front of me will take me to the shopping area.

There are tall buildings all around the station but the multi-storey car park is farther away.

Other people who disembarked from the 11.27 train cross the road beside me while the green walking man counts down. The knowing pace of the man in front of me leads me in the right direction, across paved pedestrian areas.

The shopping area is busier than I expected. It will be even busier in fifteen minutes when the office-workers spill out of the high buildings, like ants from an aggravated nest, to buy lunch.

A young boy who is close by complains to his mother. ‘Get in the pushchair!’ she yells, provoking a tirade of screams.

Blustery breezes stir up children. They want to run. Children in a playground are like birds when they play on a strong breeze. There is excitement and expectation in the air of a good breeze.

A young woman sweeps past on a skateboard, putting one foot down to push the skateboard on as she cuts in front of me. She weaves quickly through the people ahead. My gaze follows her until she disappears into the crowd. Then I see it.

The car park is a looming shadow stealing the sunlight from the street farther on; a concrete mass that peers over the top of the shops in the structure of a layer cake.

This is the street that Louise fell into.

At the top of the car park there is a wall. Somehow Louise fell over the top of that wall.

The sky is an innocent, denying blue today. Nothing happened up here, it tries to say.

But something did.

Picture after picture of this street and that car park are in my head. The images I have studied on my laptop in the last two days.

What happened, Louise?

I think she knows I have come here to find out. I think this is what she wants me to do.

The flow of people carries on into the town. A fast-running river of humanity.

I am looking for the narrow alley I have seen on Google Earth images that runs between two of the shops, to a pedestrian entrance at the side of the car park.

Three woman cross the pavement in front of me, from one shop to another. I stop to let them pass.

There is another skateboarder ahead, using a metal bicycle stand as an obstacle to perform tricks. The stand is outside a shop door that I have stared at in news articles.

It is the door.

The shop.

Louise fell onto this pavement, in that place.

I do not walk on. I can’t move. My feet are stone. The ground is thick mud to be waded through and my trainers are stuck in the sludge.

There is no mark, no rusty iron-looking bloodstain to say she was here. Nothing. It is as if the fall that ended her life, and began mine, did not happen. The sky, the car park and pavement all cry out. It was not me! Nothing happened here!

But something very wrong happened here. Women don’t just fall over car-park walls.

This heart must have pumped the blood through her broken body while she lay here.

The alley I have been looking for is on the left: a metre-and-half-wide rabbit-hole.

The block paving carpeting most of the town centre doesn’t reach into the shadowy environment of the alley. This area of Swindon, that’s hiding behind the shops, must have been built in the 1970s concrete explosion.

No one else is walking through here but there’s a man sitting on the floor a few metres ahead, on a filthy sleeping bag, with a dog; both have their legs stretched out. The man’s back rests against the wall, his hand repeatedly stroking the dog that’s lying flat beside him.

The man’s dirt-stained jeans are torn and fraying at the knees.

The dog is a small crossbreed that must include some sort of terrier DNA. Its brown eyes look at me, without any movement of its head.

There’s a presence around the man, more than in his brown-shaded aura, that says he’s given up hope of being anywhere else but on the street.

Three takeaway coffee cups stand beside the dog. I presume they’re empty and probably left there to say he doesn’t want gifts of coffee, just money. But money for what? He needs to feed the dog as well as himself and most hostels will not feed the dog.

Читать дальше