At the dawn of the 20th Century, the disturbing strangeness was displaced, no longer in a mysterious Other, but in oneself; in the darkness of one’s own psyche. [BAC 12, p. 184, author’s translation]

While between 1801 and 1840, electricity represented a counter-culture to atheism and materialism, capable of giving life back to the deceased, from 1840 onwards, it became the guarantor of the standardization of mores and a certain representation of happiness. Its developments thus marked the domination of Man over the evolution of his species.

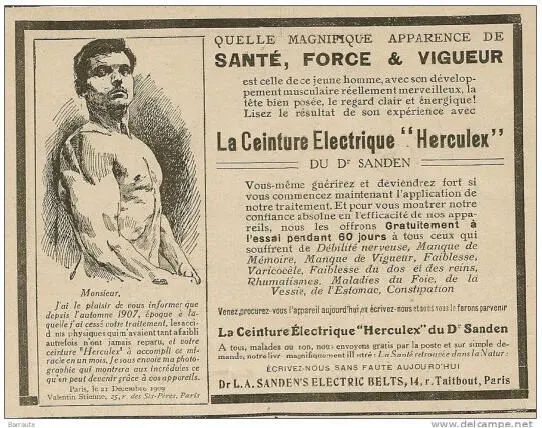

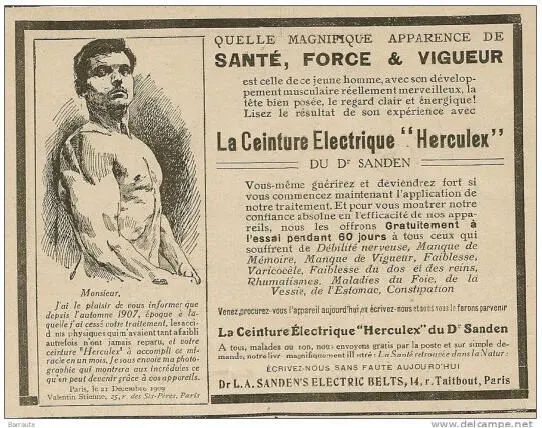

Figure 1.5. French advertisement dating from 1911 for the “Herculex” electric belt

Electrical treatments were seen as universal remedies, or in any case were disseminated as such within public opinion. Everybody could compensate for the weaknesses of their animal fluid and re-establish good connections between their consciousness and their body. Devices were becoming more compact, easier to handle, resulting in a wave of companies producing healthy electrical items. These paramedical products, such as the electric belt, easily accounted for a quarter of advertisements in 1880 [LOE 99].

These devices referred to the fact that in addition to taming the world, bringing light and progress to it, electricity was able to discipline the body and mind. This medical movement, which had its roots in the second half of the 18th Century, could have died out in the face of the uncertain results initially brought about by electrical treatment. Because it corresponded to a time when society was looking for new, stable and rational points of reference to regulate the lives of individuals, its posterity in the history of neuroscience, understood in the broadest sense, is still relevant today. These applications of electricity to a body that had symbolically become a machine could be conceived as a step contrary to hypnotism, insofar as it was not a question of reaching consciousness by disconnecting its link with the body but of intervening directly on the cerebral circuits to regulate behavior. In the context of the development of electrotherapy rooms, we can speak of a naturalization of behavior. While convulsion referred to illnesses that are difficult to differentiate from each other, electricity appeared to be an instrument that could act both on the frozen condition and on the disordered movements, able to differentiate a psychological illness from an organic pathology. Thus, cataleptics, hysterics, ecstatics and epileptics resembled each other and merged together in the medical discourse, in that their lists of symptoms had in common that they did not present a visible organic disorder:

Others, such as the supporters of the École de la Salpêtrière in the 1880s, made it a simple symptom combined with other neuroses: hysteria above all, but also ecstasy, epilepsy, apoplexy, death, chorea. Some speak of ‘hysterical catalepsy’, others of ‘cataleptic ecstasy’; others still of ‘hystero-catalepsy’. [BAC 12, p. 173, author’s translation]

The excerpt from an article in the French newspaper Le monde illustré , dated August 14, 1887, describing the intense therapeutic activity in the electrotherapy department of Salpêtrière, uses the argument of the number of patients treated to assert the effectiveness of electrical treatments. This point underlines the fact that this treatment responded to a societal problem involving ailments about which little was known but which affected a large number of people:

Thousands of patients have been treated in recent years at the Salpêtrière. At each consultation, the average number of patients varies between two hundred and fifty and three hundred. […] It’s called the electric bath. Under its influence, we can observe various physiological phenomena (heat, blood circulation, etc.), too technical to find their place here. Localized electrification is done by means of appropriate exciters. The main ailments that are treated at the Salpêtrière clinic belong to two classes; nervous diseases (hysteria, neuralgia, all kinds of paralysis) and nutritional diseases in which we understand dyspepsia, stomach dilatation, chlorosis, anemia, rheumatism, etc. The ever-increasing number of patients coming in for each consultation is the best proof of the effectiveness of this treatment. Already known, but not yet known enough, this new therapeutic method, which has already taken the largest extension, is destined for the brightest future. 14 (author’s translation)

In addition, the development of psychoanalysis and Charcot’s therapeutic hesitations moderated what could be conceived as a general craze for electrical interventionism on mental ills. Freud, who was first interested in Erb’s work, ended up considering this treatment as chimerical:

Whoever wants to make a living from the treatment of nervous patients must obviously be able to do something for them. My therapeutic arsenal contained only two weapons: electrotherapy and hypnosis, as sending to a hydrotherapy facility after a single consultation was not a sufficient source of gain. I referred to W. Erb’s manual for electrotherapy, which gave detailed prescriptions for the treatment of all the symptoms of nervous diseases. Unfortunately, I soon had to admit that my docility in following these prescriptions was of no avail, that what I had taken to be the result of accurate observations was nothing but a phantasmagorical structure. [FRE 50, p. 40, author’s translation]

Thus, it appears that the notions of the electrical body and then of electric consciousness followed one another during the 19th Century and nourished an already well-established culture of electricity. Difficult to separate from technical advances and exploratory and therapeutic applications, medical electricity permeated research on the integration of Man in nature, on the materiality of his mental mechanisms. From the objectification of this electrical nature, an imagining of the power, technique and capacity that electricity has to change us ourselves was born. Alongside the Neohippocratic movement was also the idea that individuals possess sensitivities to electricity on which their character traits depend or influence.

1.3. Possible electrical profiling?

The notions of hot-headed, irritable temperaments that punctuated the texts of electrifying and/or galvanizing doctors until the end of the 19th Century accounted for the observations that two subjects, dead in the same conditions and not subjected during their lifetime to the same temperament, will have organs that do not react in the same way to electrification or galvanization. Moreover, this electrical individualization also influenced the person during his or her lifetime: did the person have a more explosive temperament caused by an excess of animal electricity? Or on the contrary, a softer temperament?

In 1787, Petetin drafted a typology of personalities likely to have behavioral disorders. His analysis was based on the idea that everyone has an innate quantity of electric fluid circulating in their body, which causes predispositions to these ills:

The violent & fleeting convulsions which characterize it, are announced in advance by the signs of a dominant electricity in the whole animal economy; such are the supernatural strength, inconceivable agility, the vivacity of ideas, combined with the greatest volubility in expression, a more lively heat spread over the torso, the head & the arms, while the lower extremities are usually devoid of them, a sometimes voracious appetite, the desire for cold & sour drinks, the fire of the eyes, insomnia, or turbulent sleep, all the passions of the soul, exalted. [PET, 87, p. 86, author’s translation]

Читать дальше