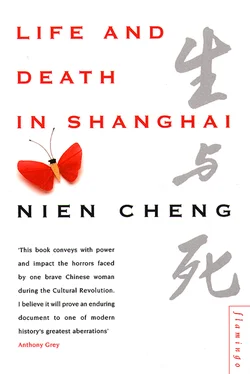

Life and Death in Shanghai

Nien Cheng

Fourth Estate

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Published by Flamingo 1995 an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

First published in Great Britain by Grafton 1986

Copyright © Nien Cheng 1986

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Nien Cheng asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollins Publishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780006548614

Ebook Edition © JUNE 2010 ISBN: 9780007375615

Version: 2019-06-13

This ebook contains the following accessibility features which, if supported by your device, can be accessed via your ereader/accessibility settings:

Change of font size and line height

Change of background and font colours

Change of font

Change justification

Text to speech

To Meiping

Cover Page

Title Page

Copyright

Note to Readers

PART I The Wind of Revolution

CHAPTER 1 Witch-hunt

CHAPTER 2 Interval before the Storm

CHAPTER 3 The Red Guards

CHAPTER 4 House Arrest

PART II The Detention House

CHAPTER 5 Solitary Confinement

CHAPTER 6 Interrogation

CHAPTER 7 The January Revolution and Military Control

CHAPTER 8 Party Factions

CHAPTER 9 Persecution Continued

CHAPTER 10 My Brother’s Confession

CHAPTER 11 A Kind of Torture

CHAPTER 12 Release

PART III My Struggle for Justice

CHAPTER 13 Where Is Meiping?

CHAPTER 14 The Search for the Truth

CHAPTER 15 A Student Who Was Different

CHAPTER 16 The Death of Mao

CHAPTER 17 Rehabilitation

CHAPTER 18 Farewell to Shanghai

Epilogue

Index

About the Publisher

PART I The Wind of Revolution

THE PAST IS FOREVER with me and I remember it all. I now move back in time and space to a hot summer’s night in July 1966, to the study of my old home in Shanghai. My daughter was asleep in her bedroom, the servants had gone to their quarters, and I was alone in my study. I hear again the slow whirling of the ceiling fan overhead; I see the white carnations drooping in the heat in the white Chien Lung vase on my desk. In front of my eyes were the bookshelves lining the walls filled with English and Chinese tides. The shaded reading lamp left half the room in shadows, but the gleam of silk brocade of the red cushions on the white sofa stood out vividly.

An English friend, a frequent visitor to my home in Shanghai, once called it ‘an oasis of comfort and elegance in the midst of the city’s drabness’. Indeed, my house was not a mansion, and by western standards, it was modest. But I had spent time and thought to make it a home and a haven for my daughter and myself so that we could continue to enjoy good taste while the rest of the city was being taken over by proletarian realism.

Not many private people in Shanghai lived as we did, seventeen years after the Communist Party took over China. In the city of ten million, perhaps only a dozen or so families managed to preserve their old lifestyle: maintaining their original homes and employing a staff of servants. The Party did not decree how the people should live. In fact, in 1949, when the Communist Army entered Shanghai, we were forbidden to discharge our domestic staff to aggravate the unemployment problem. But the political campaigns that periodically convulsed the country rendered many formerly wealthy people poor. When they became victims, they were forced to pay large fines or had their income drastically reduced. And many industrialists were relocated inland with their families when their factories were removed from Shanghai. I did not voluntarily change my way of life not only because I had the means to maintain my standard of living but also because the Shanghai Municipal Government treated me with courtesy and consideration through its United Front Organization. However, my daughter and I lived quietly with circumspection. Believing the Communist Revolution a historical inevitability for China, we were prepared to go along with it.

The reason I am so often carried back to those few hours before midnight on 3 July 1966 is not only because I look back upon my old life with my daughter with nostalgia but mainly because they were the last few hours of normal life I was to enjoy for many years. The heat lay like a heavy weight on the city even at night. No breeze came through the open windows. My face and arms were damp with perspiration and my blouse was clammy on my back as I bent over the newspapers spread on my desk reading the articles of vehement denunciation that always preceded action at the beginning of a political movement. The propaganda effort was supposed to create a suitable atmosphere of tension and to mobilize the public. Often careful reading of those articles, written by activists selected by Party officials, yielded hints as to the purpose of the movement and its possible victims. Because I had never been involved in a political movement before, I had no premonition of impending personal disaster. But as was always the case, the violent language used in the propaganda articles made me uneasy.

My servant Lao Chao had left a thermos of iced tea for me on a tray on the coffee table. As I drank the refreshing tea, my eyes strayed to a photograph of my late husband. Nearly nine years had passed since he died but the void his death left in my heart remained. I always felt abandoned and alone whenever I was uneasy about the political situation, as I felt the need for his support.

I had met my husband when he was working for his Ph D degree in London in 1935. After we were married and returned to Chungking, China’s wartime capital, in 1939, he became a diplomatic officer of the Kuomintang Government. In 1949, when the Communist Army entered Shanghai, he was director of the Shanghai office of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Kuomintang Government. When the Communist representative, Chang Han-fu, took over his office, Chang invited him to remain with the new government during the transitional period as foreign affairs adviser to the newly appointed Mayor of Shanghai, Marshal Chen Yi. In the following year, he was allowed to leave the People’s Government and accept the offer from Shell International Petroleum Company to become the general manager of its Shanghai office. Shell was one of the few British firms of international standing – such as the Imperial Chemical Industries, Hong Kong Shanghai Banking Corporation and Jardines – that tried to maintain an office in Shanghai. Because Shell was the only major oil company in the world wishing to remain in mainland China, the Party officials who favoured trade with the West treated the company and ourselves with courtesy.

Читать дальше