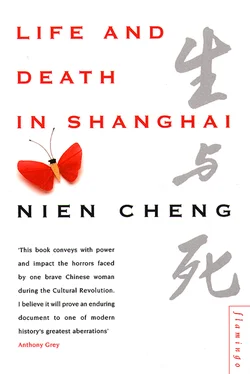

Nien Cheng - Life and Death in Shanghai

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Nien Cheng - Life and Death in Shanghai» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Life and Death in Shanghai

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Life and Death in Shanghai: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Life and Death in Shanghai»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Life and Death in Shanghai — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Life and Death in Shanghai», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘You all know who Tao Fung is. For nearly thirty-five years he was a faithful running dog of Shell Petroleum Company, which is an international corporation of gigantic size with tendrils reaching into every corner of the world to suck up profit. This, according to Lenin, is the worst form of capitalist enterprise.

‘Capitalism and socialism are like fire and water. They are diametrically opposed. Tao Fung could not have served the interests of the British firm and remain a good Chinese citizen under socialism. For a long time we have tried to help him see the light…’

I was surprised to learn that Tao Fung, the former chief accountant of our office was the target of the meeting, because I had always thought the Party looked upon him with favour. His eldest son had been sent to both the Soviet Union and Czechoslovakia for advanced studies at the government’s expense in the fifties and the young man had later joined the Party. I knew that when a student was selected to go abroad the Party always made a thorough investigation of his background, including his father’s character, occupation and political viewpoint. Tao Fung must have passed this test at the time his son was sent abroad. I could not understand why he had now been singled out for criticism.

Since the very beginning of the Communist regime, I had carefully studied books on Marxism and pronouncements by Chinese Communist Party leaders. It seemed to me that socialism in China was still very much an experiment and no fixed course of development for the country had yet been decided upon. This, I thought, was why the government’s policy was always changing, like a pendulum swinging from left to right and back again. When things went to the extreme and problems emerged, Peking would take corrective measures. Then these very corrective measures went too far and had to be corrected. The real difficulty was, of course, that a State-controlled economy stifled productivity, and economic planning from Peking ignored local conditions and killed incentive.

When a policy changed from above, the standard of values changed with it. What was right yesterday became wrong today and vice versa. Thus the words and actions of a Communist Party official at the lower level were valid for a limited time only. So I decided the meeting I was attending was not very important and that the speaker was just a minor Party official assigned to conduct the Cultural Revolution for the former staff of Shell. The Cultural Revolution seemed to me to be a swing to the left. Sooner or later, when it had gone too far, corrective measures would be taken. The people would have a few months or a few years of respite until the next political campaign. Mao Tze-tung believed that political campaigns were the motivating force for progress. So I thought the Proletarian Cultural Revolution was just one of an endless series of upheavals the Chinese people must learn to put up with.

I looked round the room while listening with one ear to the speaker’s tirade. It was then that I noticed the banner on the wall that said, ‘Down with the running dog of imperialism Tao Fung’. The two characters of his name were crossed with red Xs to indicate he was being denounced as an enemy. This banner had escaped my notice when I entered the room because there were so many banners with slogans of the Cultural Revolution covering the walls. Slogans were an integral part of life in China. They exalted Mao Tze-tung, the Party, socialism and anything else the Party wanted the people to believe in; they exhorted the people to work hard, to study Mao Tze-tung Thought and to obey the Party. When there was a political campaign, the slogans denounced the enemies. Since the beginning of the Cultural Revolution, the number of slogans everywhere had multiplied by the thousand. It was impossible to read all that one encountered. It was very easy to look at them without really seeing what was written.

The man was now talking about Tao’s decadent way of life resulting from long association with capitalism. It seemed he was guilty of having extra-marital relations, drinking wine and spirits in excess and enjoying elaborate meals, all acts of self-indulgence frowned upon by the Party. These accusations did not surprise me because I knew that when a man was denounced, he was depicted as totally bad, and any errant behaviour was attributed to the influence of capitalism.

When the man had thoroughly dissected Tao’s private life and exposed the corrosive effect of capitalism on him, his tone and manner became more serious. He turned to the subject of imperialism and aggression against China by foreign powers. To him Tao’s mistakes were made not because he was a greedy man with little self-control but because he had worked for a firm that belonged to a nation guilty of acts of aggression against the Chinese people more than a hundred years ago. He was talking about the opium war of 1845 as if it had taken place only the year before.

Though he used the strong language of denunciation and often raised his voice to shout, he delivered his speech in a leisurely manner, pausing frequently either to drink water or to consult his notes. He knew he had a captive audience, since no one would dare to leave while the meeting was going on. A Party official, no matter how lowly his rank, was a representative of the Party. When he spoke, it was the Party speaking. It was unthinkable not to appear attentive. However, he had been speaking for a long time. The room had become unbearably hot and the audience was getting restive. I looked at my watch and found it was nearly twelve o’clock. Perhaps the speaker was also tired and hungry, for he suddenly stopped and told us the meeting was adjourned until 1.30. Everybody was up and heading for the exits even before he had quite finished speaking.

Outside, the midday sun beat relentlessly down on the hot pavement. In the distance, I saw a pedicab parked in the shade of a tree. I ran to it and gave the driver my address, promising him double fare to encourage him to move away quickly.

The man who had led me into the building in the morning dashed out of the building, shouting for me to stop. He wanted me to remain there and eat something from the school kitchen so that I would not be late again. So anxious was he to detain me that he grabbed the side of the pedicab. I had to promise him repeatedly that I would be back on time before he let go.

My little house, shaded with awnings on the windows and green bamboo screens on the verandah, was a haven after that hot, airless meeting hall. The back of my shirt was wet through and I was parched. I had a quick shower, drank a glass of iced tea and enjoyed the delicious meal my excellent cook had prepared for me. Then I lay down on my bed for half an hour’s rest before setting out again in the pedicab, which I had asked to wait for me.

When I arrived at the meeting hall I was a little late, but by no means the last to arrive. I found a seat on the second row next to a pillar so that I could lean against it when I got too tired and needed support. I had brought along a large shopping bag in which I had put a bottle of water and a glass, as well as two bars of chocolate. Secure in the knowledge that I had come well prepared, I settled down to wait, wondering what the speaker was leading up to.

The hall gradually filled. At two o’clock, the same number of men mounted the platform and took up their positions. The speaker beckoned to someone at the back. I was astonished to see Tao Fung being led into the room wearing a tall dunce’s hat made of white paper with ‘cow’s demon and snake spirit’ written on it. If it were not for the extremely troubled expression on his face, he would have looked comical.

‘Cow’s demon and snake spirit’ are evil spirits in Chinese mythology who can assume human forms to do mischief, but when recognized by real humans as devils they revert to their original shapes. Mao Tze-tung first used this expression to describe the intellectuals during the Anti-Rightist Campaign of 1957. He had said that the intellectuals were like evil spirits in human form when they pretended to support the Communist Party. When they criticized the Party’s policy, they reverted to their original shapes and were exposed as evil spirits. Since that time, quick to adopt the language of Mao, Party officials used the phrase for anyone considered politically deceitful. During the Cultural Revolution it was applied to all the so-called nine categories of enemies: the former landlords denounced in the Land Reform Movement of 1950-2; rich peasants denounced in the Formation of Rural Cooperatives Movement of 1955; counter-revolutionaries denounced in the Suppression of Counter-revolutionaries Campaign of 1950 and Elimination of Counter-revolutionaries Campaign of 1955; ‘bad elements’ arrested from time to time since the Communist Party came to power; rightists denounced in the Anti-Rightist Campaign of 1957; traitors (Party officials suspected of having betrayed Party secrets to the Kuomintang during imprisonment by the Kuomintang); spies (men and women with foreign connections); ‘capitalist-roaders’ (Party officials not following the strict leftist policy of Mao, and taking the ‘capitalist road’) and intellectuals with bourgeois family origins.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Life and Death in Shanghai»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Life and Death in Shanghai» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Life and Death in Shanghai» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.