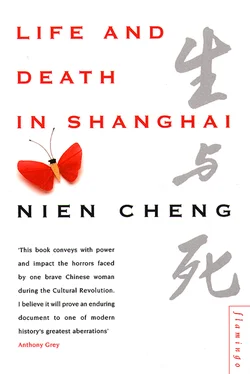

Nien Cheng - Life and Death in Shanghai

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Nien Cheng - Life and Death in Shanghai» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Life and Death in Shanghai

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Life and Death in Shanghai: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Life and Death in Shanghai»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Life and Death in Shanghai — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Life and Death in Shanghai», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

There was the sound of many people running up and down the stairs and there was loud shouting. Angry arguments seemed to have broken out overhead, followed by fighting. There was nothing I could do. I resigned myself to the possibility of the total destruction of my home. Pulling three dining chairs together, I lay down on the cushions. I was so exhausted that I dozed despite the loud noise.

After daybreak, several Red Guards and Revolutionaries threw the door open. It seemed that their dispute, whatever it was, was resolved. A girl shouted, ‘Get up! Get up!’

A woman Revolutionary told me to get something to eat in the kitchen quickly and then ‘come upstairs to do some useful work’. I went into the downstairs cloakroom to wash my hands. Looking into the mirror over the basin, I was shocked to see my dishevelled hair and puffy white face, with smudges of mud on my forehead and cheeks. Stepping back, I saw in the glass that my clothes were spattered with mud. In fact, I looked very much like a female corpse I had seen long ago being dug out of the debris on a Chungking street after an air raid during the Sino-Japanese war. The sight of that dead woman had haunted me for days. She seemed so finished, unable to do anything or even to make the smallest gesture of protest against the unfairness of her own fate. The recollection of her dead body now made me resolve to keep alive. I thought the Cultural Revolution was going to be a fight for me to clear my name. I must not only keep alive but I must be as strong as granite, so that no matter how much I was knocked about, I could remain unbroken. My face was puffy because I had not drunk any water for a long time and my one remaining kidney was not functioning properly. I had to remedy that immediately.

In the kitchen, I drank two glasses of water before eating the bowl of steaming rice and vegetables Lao Chao provided me with. It was amazing how quickly food turned into energy and how encouraging was a resolute attitude of mind. I felt a great deal better already.

A Red Guard opened the kitchen door and yelled, ‘Are you having a feast? What a long time you are taking! Hurry up, hurry up!’

Lao Chao and I followed the Red Guards up the stairs. Chen Mah also joined us. We found that the Red Guards and the few remaining Revolutionaries required our help in packing up my belongings so that they could be taken away. Anxious for them to be out of the house, I helped readily. The presence of the Red Guards and the Revolutionaries was more intolerable to me than the loss of my possessions. They seemed to me alien creatures from another world with whom I had no common language.

In the eyes of the Red Guards and the Revolutionaries, Lao Chao was not a class enemy, even though they probably thought him misguided and lacking in socialist awareness to work for me. They chatted with him freely; I could see Lao Chao was doing his best to appear friendly too. While we were sitting on the floor packing up the things that had been scattered everywhere, I heard the Red Guards excitedly discussing their forthcoming journey to Peking to be reviewed by Chairman Mao. The few who had taken part when Mao reviewed the Red Guards from the gallery of the Tien An Men Gate in Peking on 18 August were describing their experience with pride. They spoke of the role of the Army in organizing their reception in Peking, in providing them with accommodation and khaki uniforms and in drilling them for the review. It was the Army officers who had selected the quotations and slogans the youngsters were to shout.

I was interested in what the Red Guards were saying. It seemed the Army was working behind the scenes to support and direct the Red Guards’ activities.

When everything was packed, the trucks came. But to my great disappointment the Red Guards did not leave the house when the trucks drove away.

A woman Revolutionary said to me, ‘You must remain in the house. You are not allowed to go out of the house. The Red Guards will take turns to be here to watch you.’

I was astonished and angry. I asked her, ‘What authority have you to keep me confined in the house?’ Disappointment so overwhelmed me that I was trembling.

‘I have the authority of the Proletarian Revolutionaries.’

‘I want to see the order in writing,’ I said, trying to control my trembling voice.

‘Why do you want to go out? Where do you want to go to? A woman like you would be beaten to death outside. We are doing you a kindness in putting you under house arrest. Lao Chao will be allowed to stay and do the marketing for you. Do you know what’s going on outside? There is a full-scale revolution going on.’

‘I don’t particularly want to go out. It’s the principle of the matter.’

‘What principle? Since you don’t want to go out, why argue with me? You stay here until we decide what to do with you. That’s an order.’

She swept out of the house. I was furious but there was nothing whatever I could do.

I was given the box spring of my own bed placed on the floor to sleep on. A change of clothes and a sweater hung in the empty cupboard. A suitcase containing my winter clothes and the green canvas bag with a quilt and blankets for the colder days were left in a corner of the room. Besides the table and chairs in the kitchen, I was left with two chairs and a small coffee table. The Red Guards detailed to watch me sat on these two chairs outside my room so that I had to sit on the box spring on the floor. Every now and then one of them would open my door to see what I was doing. The only place where I had some privacy was my bathroom.

My daughter was allowed to live in her own room but I was not allowed in there or to speak to her when she came home which was very seldom as she had to spend more and more nights at the Film Studio taking part in the Cultural Revolution. In the evenings, I would gently push the door of my room open hoping to obtain a glimpse of her as she came up the stairs. On the nights when she did come home and we managed to look at each other, I felt comforted and reassured. Generally I would sleep peacefully that night.

Lao Chao went to market to purchase food, but neither he nor my daughter was allowed to eat with me. The Red Guards had a rotation of duty hours so that they went home for their meals. At night, one or two of them slept on the floor outside my bedroom on a makeshift bed.

Two days after I was placed under house arrest, Chen Mah’s daughter came to fetch her mother. We had a tearful farewell. Chen Mah wanted to leave me a cardigan she had knitted but the Red Guards scolded her for lack of class consciousness and refused to let her hand it to me. ‘She won’t have enough clothes for the winter. She isn’t very strong, you know,’ Chen Mah pleaded with the Red Guards.

‘Don’t you realize? She is your class enemy. Why should you care whether she has enough clothes or not?’ the Red Guard said.

Chen Mah’s daughter seemed frightened of the Red Guards and urged Chen Mah to leave. But Chen Mah said, ‘I must say goodbye to Mei-mei!’ Tears were streaming down her face.

One of the Red Guards became impatient. She faced Chen Mah militantly and said, ‘Haven’t you stayed in this house long enough? She is the daughter of a class enemy. Why do you have to say goodbye to her?’

When I put my arms round Chen Mah’s shoulders to hug her for the last time, she burst into loud crying. The Red Guards pulled my arms away and pushed Chen Mah and her daughter out of the front door. Lao Chao followed them out with Chen Mah’s luggage and I heard him getting a pedi-cab for them.

Longing to know what went on outside, I read avidly the newspaper that Lao Chao left on the kitchen table each day. One evening, when I went into the kitchen to have my dinner, I saw a sheet of crudely printed paper entitled Red Guard News left on a kitchen chair. The headline of the paper said, ‘Hit back without mercy the counter-attack of the class enemies’ which intrigued me. I longed to know more. There was no one about so I picked up the small sheet and secreted it in my pocket. Later, in the quiet of my bathroom, I read it. After that, I kept a lookout for any crumpled piece of paper left by the Red Guards. These handbills produced by the Red Guards were mostly full of their usual hyperbole about the capitalist class and the revisionists. However, in the course of denouncing these enemies they revealed facts about certain Party leaders which had hitherto been kept secret from the general public. I was particularly interested in reports that certain officials in the Shanghai Municipal Government and the Party Secretariat were attempting to ‘ignore’ or ‘sabotage’ Mao’s orders. The extent of conflict caused by policy differences within the Party leadership seemed far greater than I had thought. Being uncensored, these Red Guards publications and handbills inadvertently exposed some of the facts of the power struggle in the Party leadership and contributed to the breakdown of the myth that the Party leaders were a group of dedicated men united for a common purpose.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Life and Death in Shanghai»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Life and Death in Shanghai» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Life and Death in Shanghai» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.