Hughes had grown up surrounded by Protestants, in a predominantly Protestant enclave of West Belfast. When he was a child, during the 1950s, many of his friends were Protestant kids. There was an old woman who lived on the street who would spit every time he passed her house and ask if he had blessed himself with the pope’s piss that morning. But for the most part he coexisted peacefully with the Protestants around him. Hughes was not yet ten years old when his mother died of cancer, leaving his father, Kevin, a bricklayer, to care for six children alone. Kevin never remarried. Two of Brendan’s brothers emigrated to Australia in search of work, and he stepped up, helping his father raise his younger siblings. Kevin would go out to work, and Brendan would be in charge of the kids at home. His father described him, in a modest expression that still counted as the highest praise, as a ‘lad you could depend upon’.

In 1967, Hughes joined the British Merchant Navy and went to sea. He voyaged to the Middle East and to South Africa, where he witnessed up close the horrors of apartheid. By the time he returned two years later, Belfast had erupted into violence. Though he never spoke of it, Brendan’s father had been a member of the IRA in his youth. One of Kevin’s friends from that era was Billy McKee, the famous hard-line paramilitary who had helped to establish the Provos, and Brendan was brought up to revere McKee as a legendary patriot and gunman. When the family walked to Mass on Sunday mornings, they would pass McKee’s house on McDonnell Street, and Brendan felt as though he should genuflect out of respect for the man. Once, in some scullery where tea was being made after a funeral, he spotted McKee in conversation with some other adults. Brendan deliberately brushed against him and felt the bracing hardness of the .45 under his belt. Unable to control his curiosity, Brendan asked McKee if he could see the weapon, and McKee showed it to him.

When Brendan Hughes left to join the merchant navy, his father made a peculiar request: ‘Never get a tattoo.’ It was common for sailors to tattoo their bodies, and Hughes would have found himself in various tattoo parlours across Europe and the Far East, waiting while his mates submitted to the needle. But he honoured his father’s request. Kevin never gave any specific rationale for the admonition, apart from suggesting, vaguely, that a tattoo was an ‘identifiable mark’. But years later, Brendan would reflect on that moment, wondering whether his father might have had some premonition about the road that he would end up taking.

At the call house on Sultan Street, he was losing blood quickly. But not from a gunshot. When he crashed through the front window, the broken glass had severed an artery in his wrist. The call house was blown now; it would not be safe to remain there. So several colleagues hustled Hughes to another house a short distance away. He badly needed medical attention, but getting him to a hospital was out of the question: the army had sent men to execute him, and there was no policy of sanctuary that might protect him in a medical facility. The alternative was getting a doctor to come to Hughes, but that would pose a different sort of challenge. The men who tried to kill him had disappeared, but Saracens were still patrolling the neighbourhood, no doubt searching for him. Hughes was trapped inside the house, like some wounded animal, the blood pumping out of his arm with each beat of his heart.

Half an hour went by. Things were looking grim. Then Gerry Adams arrived, with a doctor. Adams might have been the best friend that Brendan Hughes had. They had met two summers earlier, during the riots of 1970, when Adams was directing rioters. Hughes couldn’t remember Adams himself actually throwing stones or petrol bombs, but he was very effective at orchestrating others. That was Adams’s role, in Hughes’s view – he was ‘the key strategist’ for the Provos, whereas Hughes was more of a tactician. Fearless and cunning, Hughes could mastermind any operation, but Adams had the sort of mind that could perceive the broader political context and the shifting tectonics of the conflict. Like a general who stays behind the battle lines, Adams was known for avoiding direct violence himself. If a convoy of cars loaded with Armalites arrived in the neighbourhood, Adams would ride in the ‘scout’ car – the one without any weapons – whereas Hughes tended to be wherever the guns were. Dolours Price liked to joke that she never saw Hughes without a gun and she never saw Adams with one. To Adams, it seemed that Hughes was always very much in the thick of things. He had a ‘tremendous following’ among the lads on the street, Adams later observed, adding that Hughes ‘compensated for any inability to articulate politically at great length by doing the right things instinctively’.

If there was something faintly patronising about this observation, it fitted, more or less, with the role Hughes saw for himself in the conflict. He regarded himself as a soldier, not a politician. He considered himself a socialist, but he wasn’t consumed by ideology. He considered himself a Catholic, too, but Adams said the Rosary and read his Bible every night, whereas it was an effort for Hughes to get to Mass. Hughes sometimes remarked that his reverence for Adams was such that if Adams told him that tomorrow was Sunday when he knew that it was Monday, it would be enough to make him stop and think twice. Brendan’s own little brother, Terry, remarked that Brendan’s real family was the IRA – and his brother was Gerry Adams.

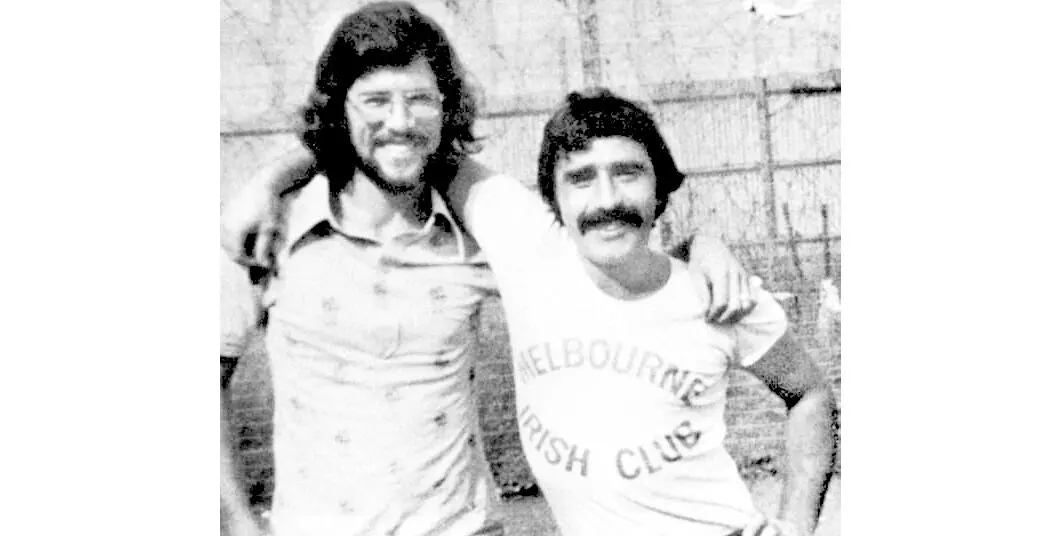

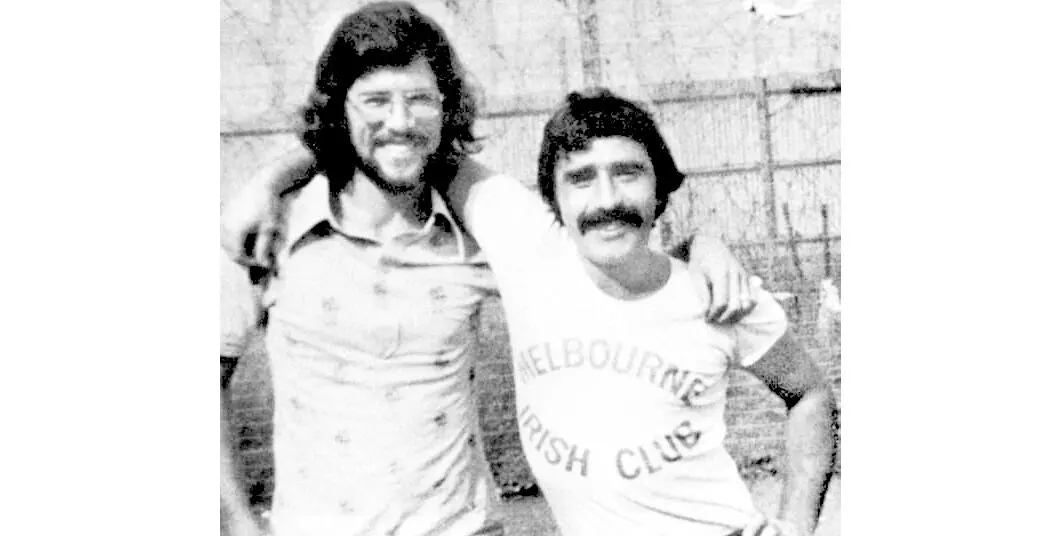

A later photo of Gerry Adams and Brendan Hughes

The doctor whom Adams had summoned was a local heart surgeon. But because he had come in such a hurry, he had no equipment. So someone fetched a needle and thread and a pair of tweezers, and the surgeon plunged the tweezers into the wound in Hughes’s arm, grasping blindly for the recessed end of the severed vessel. Securing it, finally, between the tweezers’ prongs, he pulled the artery down so that he could carefully sew it up. This rough procedure was conducted in close quarters, without anaesthetic, but Hughes could not scream, because the army was still looking for him, patrolling the street outside. At one point while the doctor was working, a Saracen pulled up right in front of the house and lingered there, its powerful engine rumbling, while they all waited, frozen, wondering if men with rifles were about to break through the door.

That Adams had come personally meant a great deal to Hughes, because it was risky for him to do so. According to the Special Branch of the RUC, Adams had been commander of the Ballymurphy unit of the Provisionals, and later became the officer commanding of the Belfast Brigade – the top IRA man in the city. He was a marked man, more wanted by the authorities than even Hughes.

But Adams felt a deep bond of loyalty to Hughes. In addition to the genuine affection they shared, it mattered to Adams that when Hughes went ‘on the run’, he remained on the streets of Belfast, rather than flee the city and retreat to the countryside or across the border to the Republic. He could have fled to Dundalk, just over the border, which had become a sort of Dodge City for republicans who were hiding out; they would sit in the pubs, getting drunk and playing cards. Instead, Hughes stayed in the city, close to his loyal soldiers in D Company, and he never let up the frantic pace of operations. ‘Local people knew he was there,’ Adams remarked. ‘And that was the kind of incentive they wanted.’

Adams saved Hughes’s life that day, and Hughes wouldn’t forget it. He could have sent someone else, but he came himself. When Hughes was stitched up and the doctor had left, Adams ordered his friend to get out of Belfast and lie low for a while. He had clearly been targeted for assassination – it was a sure bet that they would try to kill him again. Hughes didn’t want to leave, but Adams insisted. So Hughes travelled to Dundalk and booked a room in a bed-and-breakfast. But he was not one for R&R: he was itchy, impatient to get back to Belfast. In the end, he lasted only a week – which, given the pace of events in those days, felt to Hughes like an eternity.

Читать дальше

![Helen Rowland - The Widow [To Say Nothing of the Man]](/books/752764/helen-rowland-the-widow-to-say-nothing-of-the-man-thumb.webp)