‘Why are they renting and not selling?’ I ask.

Not that I can afford to buy until the divorce comes through. This is only temporary, I tell myself.

‘It’s part of an old estate. The family aren’t prepared to sell. They don’t want to break up the estate.’

I nod. I know about the family. Everybody does. There are a few stories about them, none of them particularly salutary, mostly around unreasonable rules and wilful neglect.

The agent gestures to the view beyond the cottage, over the fields and down the hill. He launches into his spiel.

‘Lovely, isn’t it? The whole valley is subject to a ninety-year-long restrictive covenant, so nothing’s been built, not even a shed, since the Second World War. People pay over a million for those few houses further up the hills …’

His voice trails away. He knows I must be aware of this. He’ll have seen my name and address on the contact form. Wife of, mother of, Mrs Henderson – is that all I am to other people? Even in this day and age, defined by my relationship to men. That’s what you get if you choose to be a full-time mother. Certainly, in this part of the county. Though choose isn’t quite how I’d put it.

Hardcastle steps ahead of me and unlocks the back door, shoving it hard to get it to open. It grinds in a painful way due to the loose stones caught under the bottom of the door.

‘You’ll be hard-pressed to find anything prettier in all of Derbyshire.’

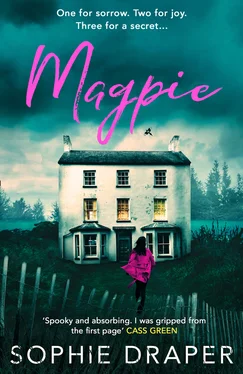

I look up – he’s right, the cottage is very pretty, in a down-at-heel, scruffy kind of way. Shabby chic, that’s how I imagine it could be, picturing it with whimsical fairy lights and vintage candles. But the view down to the reservoir still pulls my eyes. A thin trail of mist slithers out low across the surface and a large bird breaks through. Another and another, a line of geese rising up. Beating wings, open beaks, their gulping cries breaking the peace of the countryside. Their wings pull with a steady rhythm as the mist parts and coils out of place, and the yellow light from a weak sun dances briefly across the water.

The agent smooths his hands down his tie – silk, so much classier than the young man who greeted me at the office. That super-confident smile of his is making my stomach curl.

‘It’s a project, like I said.’ He croons like a jazz singer. ‘It means you’ve got the freedom to decorate exactly as you please. The view is particularly striking from the master bedroom.’

Master bedroom. As if. Judging from the floor plan on the details there’s barely enough space for one double bed and a small cabinet. I contemplate the flaking wooden windows. There’s a second bedroom under the eaves. I might have to take that one, given how tall Joe is. A ‘doer-upper’, cloistered in a long-forgotten valley, the lush slopes the select preserve of one family, a couple of farmers and a handful of rich, obsolete businessmen.

I squeeze past the buddleia bush leaning out across the doorway and duck underneath a hanging basket that trails dead leaves over my head. I eye the drunken shape of the roof, its missing tiles and the grime-encrusted, cracked panes of glass in the door. As I step inside, I see peeling wallpaper and a mustard-yellow 1950s kitchen. This place, I realise, hasn’t been touched for decades. I feel my excitement bubble.

I move into the room and then I spot the ancient red enamelled range. It’s been pushed into an old inglenook fireplace with a blackened beam above, pitted and scorched with age. I run my fingers over the grooves in the wood, peering more closely. There are markings that seem familiar, circles within circles and letters too, a W and AM , carved with a crisp precision that have nothing to do with the natural cracks from the heat. I feel myself falling even deeper in love.

‘What are these?’ I say, fingering the marks.

I know the answer, but it’s something to say. The agent leans forwards.

‘Oh, those are witches’ marks, carvings from long ago, probably from when the house was first built. People did that stuff then to ward off evil spirits. It’s quite common in this part of the county. So you’ll be quite safe here.’

He grins in a rather wolfish way for an older man. Creep , I think. Then he turns towards the back door, pulling out his mobile phone.

‘I’ll let you look around on your own.’

He’s already lost interest, swiping at the screen.

I scan the ceiling. The brochure hadn’t mentioned that the roof leaked or that there was no central heating. I can see pipes running from the side of the range to the sink, then along the wall again and up into the corner through the ceiling. I’m guessing the fire heats the hot water. I daydream of waking early in the morning, heading down the stairs in the freezing cold to stoke the ashes from the night before, piling on the logs to relight the fire in the range and generate some heat. I could put an armchair right in front of it, with that old rag rug Duncan thought I’d thrown away. It would be perfect there under my feet. Flagstones, I see proper giant slabs of flagstone. I’ve always loved the idea of having those.

I wonder if I might even be able to buy the place if and when the family decide to let it go and my divorce comes through.

I feel my anticipation grow. A new routine to take over from the old routines of my life as it was before. I’ve been with Duncan for so long, ever since we were students together at the veterinary school in Nottingham. It’s hard to conceive of a life on my own.

Though, not quite on my own.

Joe has to come with me. I can’t go without Joe.

And Arthur, of course.

It’ll be Duncan left on his own.

I wake. The bedroom is deathly quiet. The kind of silence that plucks the air from your lungs, eyes wide open listening for a creak in the walls, the flutter of birds in the trees, the switch of illicit shoes climbing the stairs.

It’s dark, the air cold upon my skin. I lie on the bed frozen to the mattress, legs bent, one arm under my head, eyelashes brushing against the pillow. I listen, hardly realising that I’m holding my breath until I let it go. My ribs move and I force myself to wriggle my fingers and pull one leg free from under the covers.

I have woken too early, too tense, the nightmare still filling my head. Fear pumps through my veins like a drug. It’s as if the bed, the whole room will implode, swallowing me up, dragging me down into a narrow chimney of thick stone and earth, falling, falling, scrabbling for roots and clumps of soil but unable to grab hold, water gushing through the gaps. I am Alice in her Wonderland, too big for the space, too small to fight back, too disbelieving of my fate, as I’m sucked down into a vortex of my own making.

I gasp and sit up, pulling myself out but into yet another new nightmare.

Joe?

I’m panting, dragging great lungfuls of air into my chest. I reach for the bedside lamp, pick up the clock and cast my eyes around the room. I see the spill of daylight growing through the gap in the curtains. For a moment it all seems strange, an alien place I’ve never seen before. The clock has a new face, the curtains a different pattern. Even the fragile dawn is a strange colour, sharper, cleaner, more luminescent than before.

I exhale and place the clock back on its table. I let the brightness bring me slowly back to life. That’s when the memory taunts me. The memory of my son.

I remember the sweaty, musky scent of him that clings to his unwashed clothes, the way his hair falls in lush waves across his cheeks. I hear his music, the thudding beat asserting his presence in the Barn. I smell the cold air on his coat, the dead leaves under his feet, the ice upon his skin. And something else – a damp, earthy, rotting kind of smell, like mushrooms spawning in the dirt.

Читать дальше