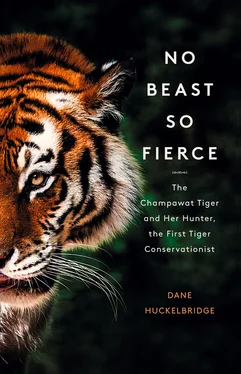

Third: Bengal tigers are strong . A tiger’s jaw is capable of exerting around a thousand pounds of pressure per square inch—the strongest bite of any cat. That’s four times as powerful as the bite of the most menacing pit bull, and considerably stronger than that of a great white shark. Even Kodiak bears, which can weigh as much as 1,500 pounds, can’t keep up. The bite of a tiger can shred muscle and tendon like butter and crunch bones like we might a stale pretzel stick. And if their bite is terrifying, a swipe from their retractable claws is just as bad if not worse. A single blow from a Bengal tiger’s paw can crack the skull and break the neck of an Indian bison, and can decapitate a human. Aggressive tigers have been known to rip the bumpers off cars, tear outhouses to splinters, and burst through the walls of houses in search of food. They can drag a one-ton buffalo across a forest floor with ease, and are capable of carrying an adult chital deer by the neck as effortlessly as a mother cat does a kitten. It’s less apparent on an Amur tiger, with its heavy fur and fat reserves, but on a Bengal tiger, the musculature is unmistakable—this is the middle linebacker of the animal world, the perfect melding of power and speed.

And last: Bengal tigers are smart . Predation of almost any kind requires intelligence—a carnivore must discern what prey is ideal, where to find it, and how best to stalk it while evading detection. Tigers excel at all of the above, thanks to skills acquired during a lengthy tutelage with their mothers. Cubs typically stay with their mothers as long as two and a half years, during which, under her ceaseless care, they learn the many, complicated tricks of the trade. And tricks, at least according to some sources, they most definitely are. During the British Raj, hunters took note of tigers that could imitate the sound of the sambar deer—what naturalist and tiger observer George Schaller would later refer to as “a loud, clear ‘pok,’ ” although he admitted to having seldom heard them make the noise while actually hunting. In colder climes to the north and east, there exist tales of tigers imitating the calls of black bears, ostensibly so they could snap their spines and dine on their fat-rich meat. Tigers frequently adjust their attack strategies to fit their quarry, and whether it’s chasing larger animals into deep water where they are easier to kill, snapping the leg tendons of wild buffalo to bring them down to the ground, or flipping porcupines onto their bellies to avoid their sharp quills, tigers are quick studies in the arts of outsmarting their prey. This intelligence, coupled with their innate athleticism and sizable frame, makes for one exceptionally effective natural predator.

Indeed, when one considers the raw physics of a collision with a five-to-six-hundred-pound body moving at forty miles an hour, the equation starts to feel less like one belonging to the natural world, and more akin to that of the automotive. Only this Subaru is camouflaged, all-terrain, and has one hell of a Klaxon—not to mention a grill bristling with meat hooks and steak knives. And when it comes to putting a tiger in its tank, this high-performance vehicle runs almost purely on meat—sometimes as much as eighty-eight pounds of it in one sitting. It has its own favorite sort of prey, the hooved, meaty mammals that graze in its domain. But a hungry tiger will eat almost anything.

Of course, there are the more pedestrian items on a famished tiger’s menu. Turtles, fish, badgers, squirrels, rabbits, mice, termites—the list is long and inglorious. But then there are the more impressive items that a tiger may take as quarry when the conditions are right. In addition to bears and wolves, tigers have been documented ripping 15-foot crocodiles to pieces, tearing the heads off 20-foot pythons, and dragging 300-pound harbor seals out of the ocean surf to bludgeon on the beach. Bengal tigers in northern India are known to have killed and eaten both rhinos and elephants, and while they tend to prefer juveniles for obvious reasons, full-grown specimens of both species have been victims of tiger predation. In 2013, a rash of tiger attacks upon adult rhinos occurred in the Dudhwa Tiger Reserve in northern India, with a 34-year-old female rhino—almost certainly over 3,000 pounds—being killed and eaten. In 2011, a 20-year-old elephant was killed and partially eaten by a tiger in Jim Corbett National Park, and in 2014, a 28-year-old elephant in Kaziranga National Park farther east was killed and feasted upon by several tigers at once. Keep in mind, a mature Indian elephant can weigh well over five tons; the Bengal tigers responsible essentially took down something the size of a U-Haul truck just so they could gnaw on it. Oh, and lest we forget—tigers eat leopards too, fearsome predators in their own right. Among the most muscular and ferocious of predatory cats, leopards are themselves capable of downing animals five times their size, and hoisting their huge carcasses high up into the trees. However, that doesn’t seem to discourage Bengal tigers from crushing their spotted throats and dining on their innards.

But of all the wide variety of flora and fauna the tiger habitually kills, all the Latin dictionary’s worth of taxonomy it is willing to regularly gulp down its gullet, there is one species that is notably and thankfully absent: Homo sapiens. Perhaps it’s our peculiar bipedalism, our evolutionary penchant for carrying sharp objects, or even our beguiling lack of hair and unusual smell. For whatever reasons, though, Panthera tigris does not normally consider us to be edible prey. As we know, they go out of their way to avoid interacting with our kind. But as many a tiger expert has noted, what tigers normally do, and what they’re capable of doing, are two very different things. And in the case of the Champawat Man-Eater, normality seems to have vanished the moment our species stole half its fangs—a transgression that the tiger would repay two hundred times over in Nepal alone.

CHAPTER 2

THE MAKING OF A MAN-EATER

Long before an emboldened Champawat Tiger was terrorizing villages and snatching farmers from their fields, it was a wounded animal convalescing deep in the lowland jungles of western Nepal, agitated, aggressive, and wracked with hunger. And it is a safe bet that its first attack occurred there, in the rich flora of the terai floodplain, the preferred habitat of the northern Bengal tiger. The terai once was—and still is, I discovered, in some isolated areas—a place of enormous biodiversity and commanding beauty. Dense groves of sal are interspersed with silk cotton and peepal, imposing trees that look as old as time. Islands of timber are encircled by lakes of rippling grasses, their stalks twice as high as the height of any man. Chital deer gather at dusk along the rivers, wild pigs root and trundle through the leaves, and even the odd gaur buffalo can make an appearance, guiding its young come twilight toward the marshes to feed. But there are people who make their home here as well: the Tharu, the indigenous inhabitants of the region who lived in the terai then as some still do today, in close proximity and harmony with the forest. Residing in small villages composed of mud-walled, grass-thatched structures, and combining low-impact agriculture with hunting and gathering, the Tharu are experts not just at surviving but thriving in a wilderness where few others can. The spirits of the animals they live beside are worshipped, and the largest of their trees are as sacred as temples. In short, they are a people with tremendous respect for and knowledge of the natural world. And the Champawat Tiger’s first victim was almost certainly one of them.

A woodcutter, possibly, or someone harvesting grass for livestock. A worker whose stooped posture resembled an animal more than a human. Perhaps he was a hattisare —a Tharu working in the royal elephant stables, on his way into the land’s bosky depths to harvest the long grasses upon which the elephants fed. It is a scene still repeated in the forest reserves of Nepal to this day, and instantly retrievable. We can imagine it: the air spiced by the curried lentil dal bhat simmering on the fire, and rich with the tang of fresh elephant dung. Our hattisare rides through these aromas atop a lumbering tusker, ducking his turbaned head to clear the low-hanging branches of trees, guiding his tremendous mount with gentle prods of his feet away from the stables toward the dense jungle and grasslands beyond.

Читать дальше