The irony is that Rowland’s own belonging might have been the tiniest bit in doubt too. I say this because stories about my grandfather suggest he was never quite the man that legendary Uncle Bob – Robert, his brother – had been. Bob always seemed the more able. There is a suspicion, then, of what Freud called ‘projection’. This is the idea that we transfer onto other people those aspects of ourselves we find least congenial, thereby restoring a sense of our own flawlessness. In couples psychotherapy, for example, a wife might say of her husband, ‘I don’t trust him.’ But unconsciously what she is indicating is, ‘I am not to be trusted.’ So if, as second fiddle to Robert, Rowland felt inadequate, it’s possible that he saw in the pairing of David and Colin an echo, psychologically speaking, of his own situation. Thus David was the superior and Colin the inferior partner. Expelling Colin represented the purging of an inferiority that was Rowland’s own.

If that hypothesis is credible, then berating my father for his ‘uselessness’ was for Rowland an unconscious way of railing at a deficiency of his own, relative to his brother. It was a personal deficiency that he dealt with by contaminating his son with it. He then cited his son’s deficiency as a justification for banishing that son like a leper. Unluckily, however, you do not get rid of a disease by passing it on to someone else. It sticks. In any case, Colin had already been invaded by a disease of his own that would derange him more completely.

On the other hand, we could say that Rowland took the tough decision. From this perspective, he was acting like a true leader. After all, when decisions require little discretion, we are not really deciding at all. We are pushing at an open door. Say I’m checking into the Grand Hotel in Brighton and am offered a choice between two rooms at the same tariff. One is at the front with a sea view; the other is at the back, overlooking the car park. It is obvious which one I should take.

But when I quiz the receptionist further, I discover that the sea-view room is poky. Between it and the sea runs a noisy road. The back room, by contrast, is spacious and quiet. Now I have a genuine dilemma, which calls for a true decision. Choosing between family and business is a genuine dilemma too, because the arguments on both sides can never be exhausted. The decision can always be deferred. What’s more, families and businesses are not two hotel rooms but apples and oranges. We are not comparing like with like, so how on earth are we to weigh them up?

So tricky are such genuine dilemmas that reason can take us only so far towards resolving them. That is why the Algerian-French philosopher Jacques Derrida, for example, writes about the ‘madness of decision’. fn2Whatever the logical steps involved in the run-up to it, the decision itself marks a leap into the dark. That leap is the point at which reason can no longer help, because now it’s a matter of acting. You close your eyes and jump.

That’s what Rowland did. He acted with the unavoidable madness of all action. By not ducking the decision, he was, for good or for ill, accepting accountability. Was this something that he had learned in wartime? He had won an OBE for his actions. If Colin was the poorer performer, keeping him on might have put the business at risk. That would have impacted everyone. We can choose to see Rowland’s decision not as the cold-hearted rejection of his firstborn, but as a judicious move for the greater good. After all, the gravity of the decision can’t not have affected him.

An organisation perishes if it doesn’t work, so ultimately it has to put its own prosperity above the individuals in it. There is no autonomic system operating in a business such as there is in a human body. A business has no respiratory function that carries on regardless of the will of its owner. It must remember to breathe.

This need on the part of a business to keep its purpose at the front of its mind has an impact on the relationships among the individuals in it. We’ve seen how the roles played by Colin and David were reversed. Where the semi-son became the outsider, the outsider became the semi-son. That reversal took place because David’s input was perceived as more vital to the company’s commercial aims. A valuation took place. But such valuations take place in any situation where we bind together with others in a joint endeavour. The endeavour could be trivial, such as assembling a flat-pack wardrobe with a friend, or hold national significance, like starting a political party. No sooner do we find ourselves in such partnerships than a third element comes and stands over the relationship between us, like a master with its back to the sun. This third element is the goal that we’re trying to attain. It’s this goal that has convened us, and both of us have a duty to fulfil it. No matter how close the bond between the individuals involved, it takes second place to the goal that has brought them together.

As soon as the work begins, however, we become highly sensitive to the level of contribution that we are separately making. In particular, we are attuned to whether our partners are doing their share. We carry a secret measure, like a microscopic, translucent gauge within us, from which we’re always taking readings, working out who’s showing the greater commitment to the joint goal. I call it the ‘contribution sextant’. If, at any moment, we judge that our partner is more distant in his or her heart from that goal, we rate them as less valuable than we are. A draught of estrangement passes between us. To begin with, we ignore it. Generally, we’d rather get on with people than point out their failings, especially if we’re supposed equals before the same goal. Over time, however, the tolerance dries up, becomes brittle. Sooner or later it snaps and, with an aggression that’s more or less passive, we’ll call out the difference between their contribution and ours.

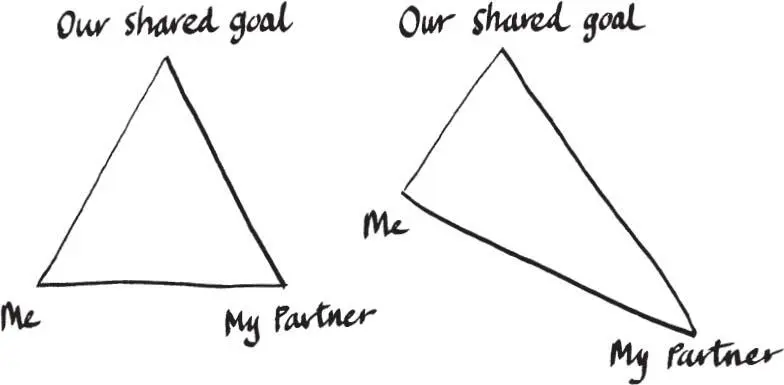

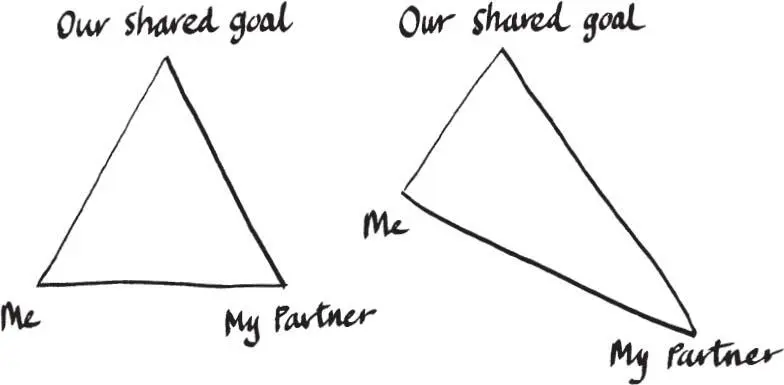

Compare the two triangles below. The first is equilateral, so we see a perfect balance. The distance between my partner and me is the same as the distance between each of us and our shared goal. The shared goal stands above us. We both have a duty to fulfil this goal. Like ladders, our separate efforts lean up towards and converge upon it. Meanwhile, a horizontal line runs between me and my partner, representing the equality that we experience as we labour at our joint task. Neither of us is supposed to give more or less than the other. The horizontal line helps us to feel we are in it together. These two factors, a shared goal and a sense of equality before it, create a bond. It feels right, and because it feels right, it feels good.

In the second triangle, by contrast, we see a less perfect configuration. Immediately, we sense relative disorder. My line to the shared goal is shorter, and my partner’s correspondingly longer. That indicates a greater commitment on my part to the shared goal. The shorter line has the inevitable consequence of lifting me higher up the picture than my partner. This elevated position is in effect the moral high ground. From here I can look down on my partner.

My partner’s perspective is altered in proportion. Now he is in a position of inferiority relative both to me and to the shared goal. How will the new configuration affect our relationship? We no longer have the line of equality keeping us in balance. What’s more, the distance has grown, and the new angle means we can’t see as much of each other. Our relationship suffers from the asymmetry, and we both know it. The disjointing of the triangle leads to an inner knowledge, shared by us both, of damage done.

Читать дальше

![Helen Rowland - The Widow [To Say Nothing of the Man]](/books/752764/helen-rowland-the-widow-to-say-nothing-of-the-man-thumb.webp)