The robbery had a further disquieting aspect. Our apartment was locked and on the first floor. Accessing it required the main door of the building to be breached, as well as that of the apartment itself. Simone herself had been away while I was with Andrea, visiting friends in Provence. We couldn’t help wondering whether our Moroccan neighbours were the culprits. Maybe we were being as racist as the immigration police, but who else would have known that we were both away? Apart from Andrea, that is.

I had arrived in Perpignan with Simone on New Year’s Eve, 1986. Simone had been back home for Christmas to visit her parents, and had scooped me up for the return leg. The coach journey from Victoria station took a gruelling twenty-four hours. We pulled into Perpignan’s central square just as the restaurants were closing and the floors being swept.

That first night, I had a dream in which I was the father of three daughters. There was little narrative, more a single tableau for me to behold: the three girls and me, as if I were being shown a photograph.

It was rare for me to dream, or at least to remember a dream. Maybe what provoked it was the combination of the travelling, the unfamiliar bed, the first night spent with Simone, and the apprehension induced by having taken this leap into the unknown of another country. More unusual, however, was the fact that the dream featured a family. Of all the fantasies regarding my future that I nurtured at the age of twenty-one, none included children. The very word ‘family’ freaked me out. It brought up visions of The Waltons and other cheesy Americana. The concept of the nuclear family rankled, as it diminished alternative ways of life. Family was so mammalian : whither had our human faculties disappeared in this guileless mimicry of the animal world? With a young man’s single-mindedness, I also thought that having a family would attenuate my heroic purpose in life. Not that I had one.

What was stoking all this aversion? That lack of tethering to my birth family, no doubt. It was as if, growing up, a centrifugal force had whirred in the house, like the drum in a washing machine, spinning my parents and sisters into different corners. Not to mention the central fact of my father’s decline. For me, belonging to a family meant living in a micro-culture that had failed to coalesce around anything much, save for that heart of darkness.

In short, dreaming about having a family should have made me anxious. In fact, it felt benign. By the time I dreamt the dream, on the first morning of 1987, Simone was pregnant.

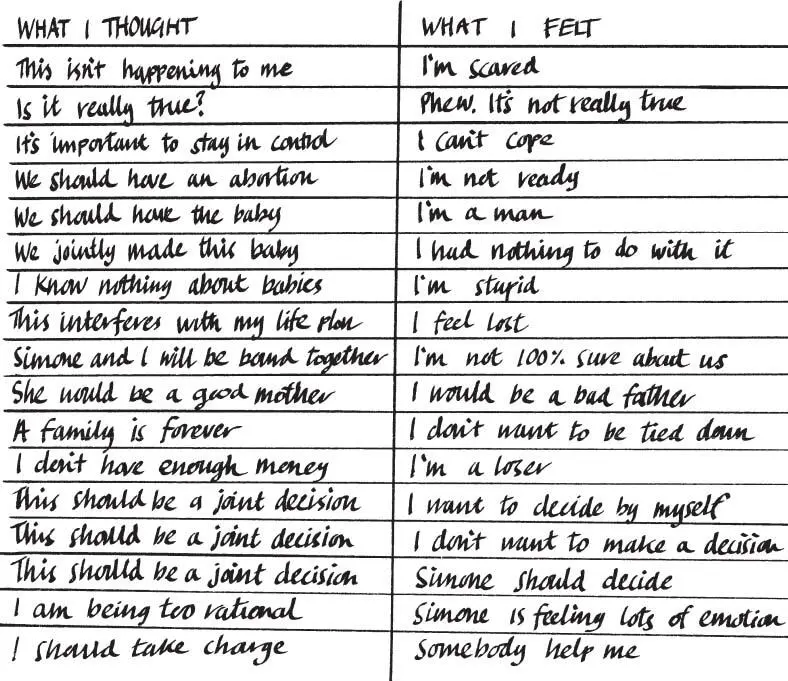

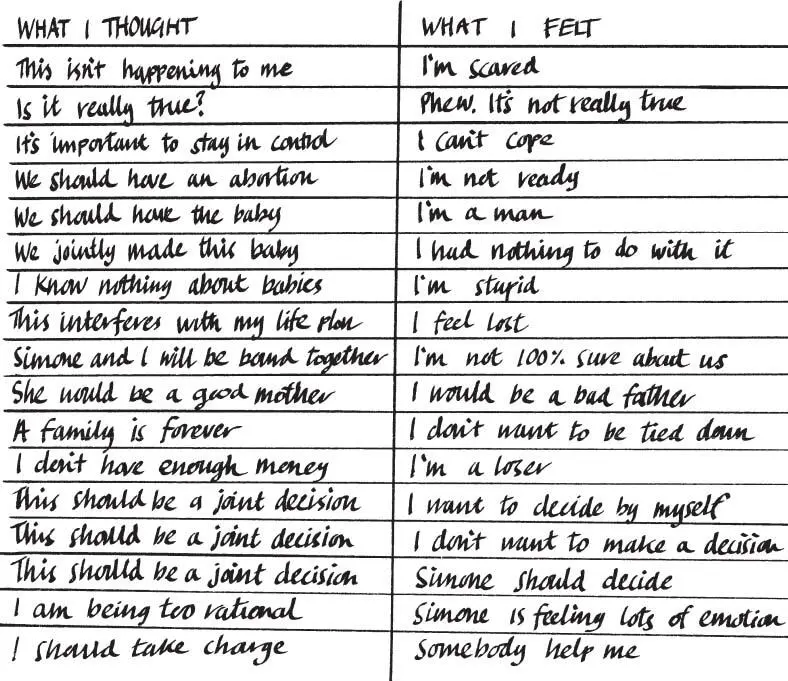

It was another three months before we knew. Since we were using birth control, it was a while before it crossed our minds, but eventually Simone went to the doctor. When she came home with the news, I sat on the bed and buried my face in my hands. Here is some of what I thought and felt:

A few weeks later, Simone went back to the doctor for a scan. This time I accompanied her. Given we were in France, where eating rare red meat was the norm, he warned us about toxoplasmosis, a blood disease carried by undercooked food, and the dangers it held for pregnant women. Simone and I later laughed at how typically French the whole thing was. Other than that, all was routine. The doctor performed the scan. To me, the fuzzy black and white image was as indecipherable as a galaxy. The foetus lay inches beneath the skin yet seemed as remote as an astronaut blurred by cosmic sleet. When we asked about the gender, the doctor suavely replied, ‘ À mon avis, c’est une fille. ’ ‘In my opinion, it’s a girl.’ Sweet Pea was frolicking like a seahorse in her amniotic bath.

The pregnancy came out of the blue. We hadn’t planned it, we were using contraception and, for the purposes of bringing up baby, our circumstances were far from ideal. Simone was on a fixed-term contract; I was on no contract at all. Neither of us had a home or a job in the UK to go back to. We’d been together a few short months, and were a long way from committing to each other as life partners. My desire to start a family was zero. To the extent that I had plans, they were as self-oriented as any twenty-one-year-old’s plans would be. What’s more, the model of fatherhood that I held in my mind was shaped by my own father, Colin. If that was what fatherhood looked like, then thanks but no thanks.

So there were more than a few enemies that the pregnancy needed to defeat. On paper, it shouldn’t have won. But despite all those forces lined up in opposition, maybe a part of me wanted what shouldn’t have happened to happen – to say nothing of Simone’s own unconscious motives. Was I surreptitiously on the lookout for a chance to become the father whom I wished I had had? It was more than not wanting to be his son. That agenda I was already enacting. On my eighteenth birthday I had declared that I would no longer address my father as ‘Daddy’ (so babyish!), but by his first name, ‘Colin’. It felt awkward but I was militant – in the way that a young boy is militant when he runs away from home with a knapsack and a bag of crisps.

Was I now going one step further, by wresting the role of father from Daddy? I did take the first opportunity available: conception occurred within hours of being dropped off from the coach. It was as if I had seen a way to reinstate the figure of thrusting fatherhood which, with Colin’s demise, had been swiped away. I was young and healthy, with all my life ahead. If he couldn’t do it, then I would. Rather than observing his position as if through binoculars, I would commandeer it. I would lift from Colin the burden of being a father himself, freeing him to slay his own demons and return to vigour.

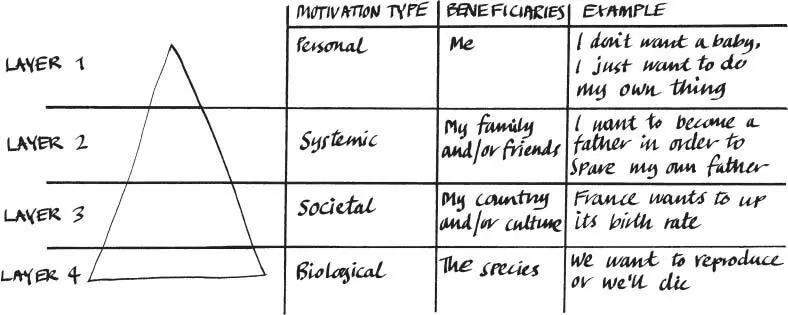

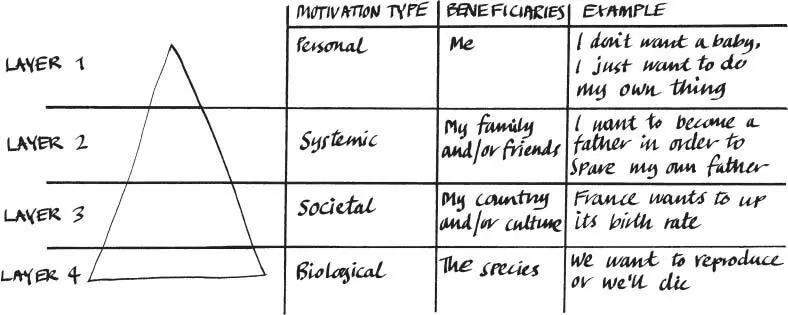

Who knows. Beneath our stated intentions, the layers ladder down like strata on a cliff face. I would group these layers into four, as in the triangle below:

1 We all have a top layer of selfish interests. I was concerned that my own life should go well, without having a baby to worry about.

2 At the next layer down, I was heeding an unconscious call to repair the damage in my family system (hence the ‘systemic’ label). This I would do by pumping life back into the punctured figure of the father, substituting myself for Colin.

3 Beneath layer two sits that level of motivation which keeps us in line with our society’s expectations. Largely without thinking, we will adopt prevailing norms, seeking not to stand out. It takes effort to be different: fitting in is so much easier. Hence the dominance of that nuclear family. On our arrival in France, the government was just launching an initiative to drive up the birth rate. Billboards displayed pictures of cherubic babies, accompanied by cheeky captions inviting the population to go forth and multiply.

4 At the deepest level, our motivations are bestowed on us by the species as a whole. The species is fixated on its own survival. We need life to go on, even if not all of us will serve as its agents.

The further down the triangle we go, the less conscious our motivations become. That doesn’t mean they lose power. On the contrary, we find ourselves subject to increasingly puissant forces. By the time we touch the ground floor that marks the species level, we are unlikely to be aware of any ‘motivation’ at all. Few of us will have children for the sake of preserving the species. But the fact that our minds won’t register the needs of the species – except in an abstract way – doesn’t mean that our bodies aren’t teeming with those needs. That’s the life force at work. Whatever else we might be, we are vehicles of life and its indefatigable drive to keep driving. Some of us create children; none of us created life. Although we can suppress life through contraception, abortion, and even acts of killing, we are only holding back a force that is stronger than we are.

Читать дальше

![Helen Rowland - The Widow [To Say Nothing of the Man]](/books/752764/helen-rowland-the-widow-to-say-nothing-of-the-man-thumb.webp)