A broad perspective on where there’s been progress – and where there are gaps – comes from the World Economic Forum’s annual analysis of gender-based disparities. In recent years it has found that the countries studied had made great strides in two key areas – health and educational attainment. The major gaps lay in two others – political empowerment and economic participation and opportunity.6 Its reports have also highlighted how women are likely to be affected by key future trends: automation will significantly affect industries in which many are currently employed, and they are under-represented in high-income and high-growth fields such as technology and science. Even countries where women have made great strides cannot be assured of future progress, explains the organisation’s head of education, gender and work, Saadia Zahidi: ‘A lot of advanced economies have stalled as they were riding the wave of the education boom among women, but if the responsibility of home and childcare is still on those women, there is a limit to how much they can do in the workplace.’7

India is a country where the growth in girls’ education hasn’t resulted in women entering the workforce in the numbers you might expect or hope for. In fact, according to the Harvard economist Professor Rohini Pande, female participation in the Indian labour market fell between 1990 and 2015, down from 37 per cent to 28 per cent. It’s not a lack of political will to get more women into paid employment, she says, or a lack of interest from women themselves. Instead, there is a significant role being played by social norms – among parents, husbands and parents-in-law – about appropriate behaviour for women. Pande’s research also suggests that while low pay is the main reason for Indian men to leave a job or not accept one, women cite family pressures and responsibilities.8

Those pressures might relate to taking care of the household, but also basic mobility, such as requiring permission to go out. As Professor Pande says: ‘It’s pretty difficult to look for a job if you can’t leave the house alone.’ Even in India’s urban areas, she and her associate Charity Troyer Moore found female workers struggling to access male-dominated networks. ‘Women often end up in lower-paid and less-responsible positions than their abilities would otherwise allow,’ they say, ‘which, in turn, makes it less likely that they will choose to work at all, especially as household incomes rise and they don’t absolutely have to work to survive.’9

Nonetheless, the experience of a country like Bangladesh, with similar social and cultural norms to India, shows that there are ways such barriers can be tackled. It has a higher proportion of working women than India, largely thanks to the development of its garment industry, where 80 per cent of the workers are female. On a trip there in 2015, I saw for myself the difference that a job in one of these factories can make to an individual’s life. In a room packed with rows of women at sewing machines, one young worker’s ID card, hanging around her neck, bore the photograph of a young boy on the reverse. She was a widow and this was her only child. His future was her biggest motivation and she was able to pay for his education thanks to her job – without it, they would both be dependent on the mercy of relatives. Indeed, Pande and Moore say the garment sector has been important for Bangladeshi women’s empowerment far beyond the factory floor: ‘The explosive growth of that industry during the last thirty years caused a surge in large-scale female labour force participation. It also delayed marriage age and caused parents to invest more in their daughters’ education.’10

In the UK much of the conversation about workplace gaps between men and women has focused on pay, especially after a 2017 law required larger employers to reveal the difference in the mean and median pay of male and female workers. As this gender pay reporting is based on averages it is in some ways a crude calculation – the airline easyJet, for example, reported a particularly large gap because men dominate its cohort of pilots, who are paid considerably more than the mostly female cabin crew.

It does, however, shine a light on representation and getting women into higher-paid roles, which is why Carolyn Fairbairn of the Confederation of British Industry welcomes it: ‘This is about fairness but it’s also about productivity in our economy and how we have businesses that have all the talents. We do not have enough women who are pilots, or CEOs who are women, or enough top senior consultants in hospitals who are women. These are issues that we now need to really grip.’11 Some believe the obligation to report has transformed companies’ conversations about gender. ‘When we’ve talked about the pay gap before, the response has always been “That must be happening somewhere else”,’ says Ann Francke of the Chartered Management Institute. Now, she says companies are being forced to confront their data and reflect on the picture it paints.12

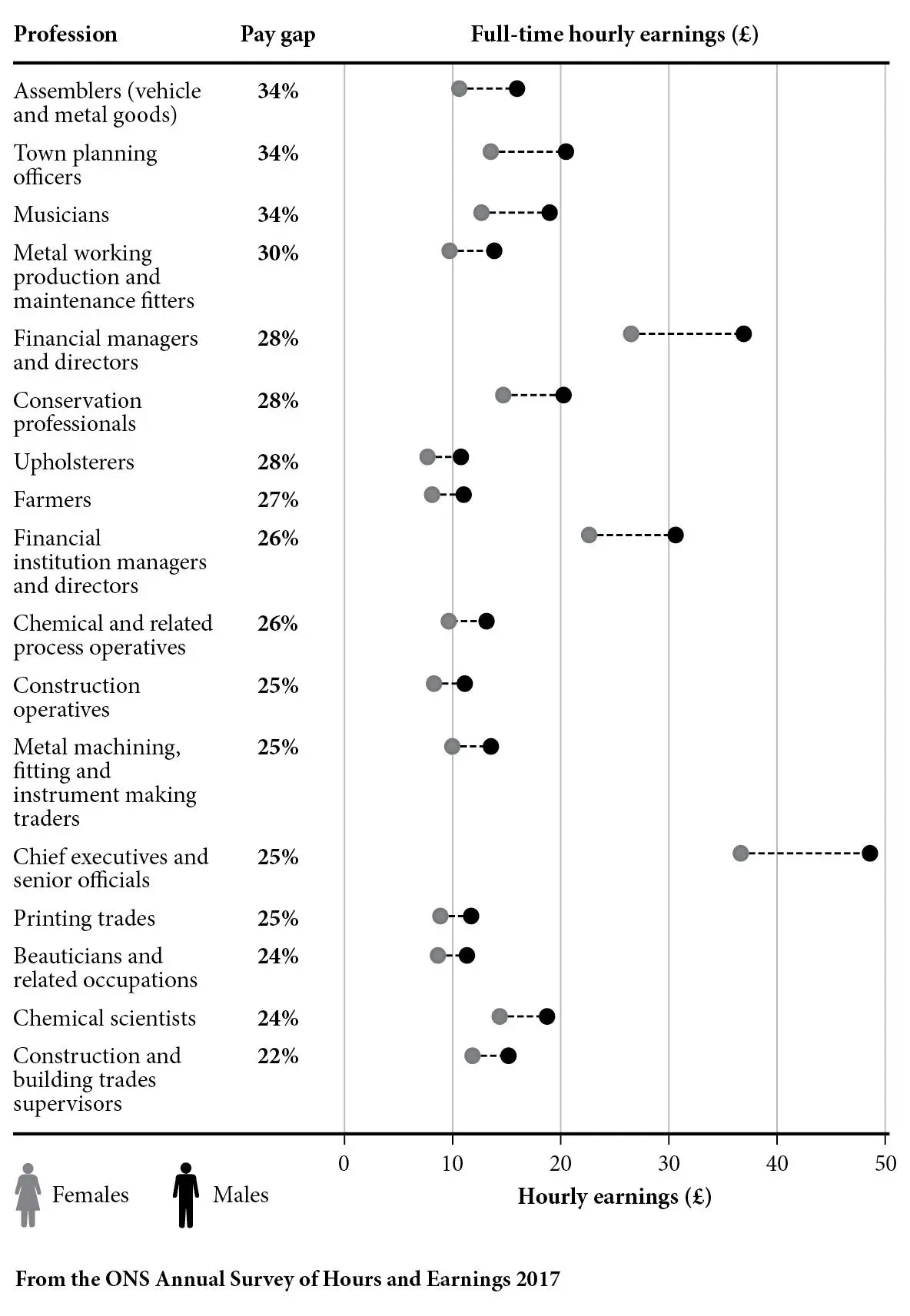

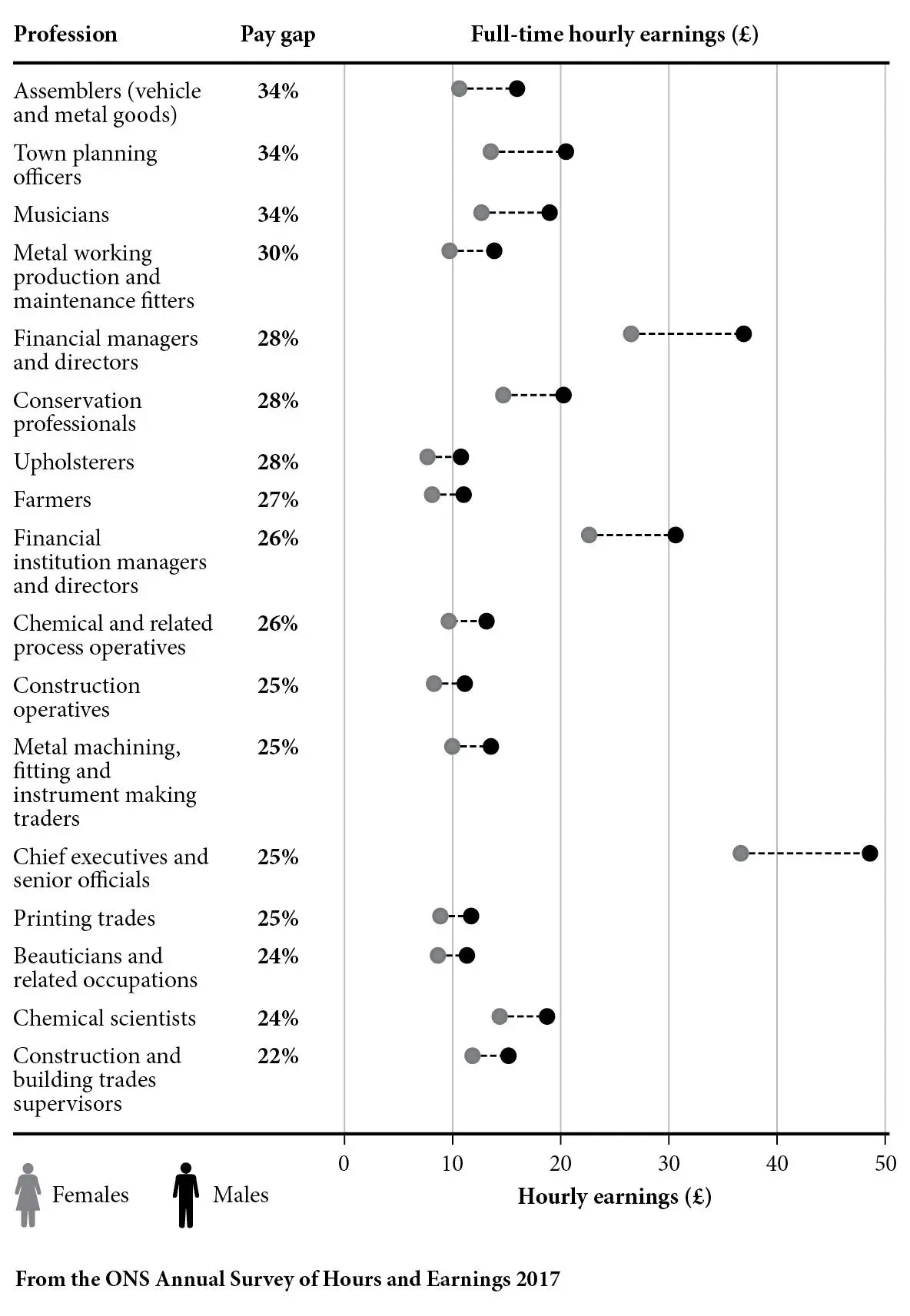

Elsewhere, other data allows comparisons of pay for men and women who have the same professional occupation. A 2017 data set from the UK’s Office for National Statistics showed considerable gender variation in average hourly earnings in many of them. Among full-time financial managers and directors, for example, men earned an average of £35.52 per hour (or £72,000 per year), and women £24.29 per hour, translating into an annual salary of around £43,000. The pattern was similar for town planning officers, musicians, scientists and chief executives. Most of the roles where the gap disappeared or was reversed, so that women were earning more (secretaries and fitness instructors, for example), had hourly earnings at the lower end of the spectrum.13

It is possible that these comparisons mask variations about the work done within the different categories: the scope and responsibility of the roles, whether the jobs were in the public or private sector, the region in which they were based and the skills, experience and competence of the individuals whose information went into the data set. But like companies’ gender pay gap figures, they can be a valuable starting point for a conversation about disparities. Perhaps the women had previously taken time out from work or been part-time for a period – but would that, or should that, fully account for the gap with comparable men once they returned to full-time?

According to the Institute for Fiscal Studies, part-time work can have a striking effect in shutting down normal wage progression. In general, pay rises with experience, but part-time workers, who are mostly women, miss out on these gains. ‘By the time a first child is grown up (aged twenty), mothers earn about 30 per cent less per hour, on average, than similarly educated fathers. About a quarter of that wage gap is explained by the higher propensity of the mothers to have been in part-time rather than full-time paid work while that child was growing up, and the consequent lack of wage progression,’ said the 2019 study, highlighting what the authors called ‘the long-term depressing effect’ of part-time work.14

At Harvard, the economist Professor Claudia Goldin has examined the way different jobs are structured in order to see how this sort of pay penalty might be addressed. She’s pointed to how some occupations – including within business, finance and the law – generally pay a premium for longer hours. A lawyer expected to be readily available for clients and working sixty hours per week, for example, is likely to earn more than double the salary of a comparable colleague working thirty hours a week. Professor Goldin says this ‘non-linearity’ arises when the job is set up or has historically been done in a way that makes it difficult for workers to substitute for one another. Within this environment, those who work shorter hours will suffer a disproportionate wage penalty.

Читать дальше