‘Something like The Lord of the Rings .’

At that point, he had still only read it the once, when he was eighteen. It was simply what sprang to mind.

‘Well,’ Walsh replied, ‘in that case why not do The Lord of the Rings ?’

Except it didn’t go like that. Not exactly. The reality behind the decision to attempt Tolkien was a lot more complicated and painful. The river of fate had many twists and turns to negotiate.

*

In the 1950s, Kamins, eldest of four New Yorker brothers, always played the dutiful son and did whatever he was told. This was the reason Jackson’s manager so loved the Marx Brothers of Duck Soup and Horse Feathers . He longed for their utter sense of anarchy, their disrespect for authority.

‘They managed to play by their own set of rules, which I never could,’ he says wistfully.

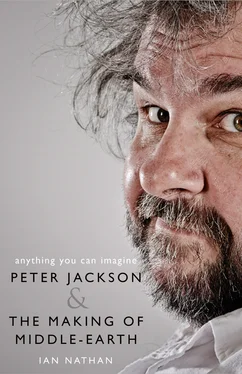

Short-haired and snappily attired (the opposite of his client), with a calm, observant, thorough manner, Kamins is a Hollywood man without the pretension. He sees the world keenly through his rimless spectacles. From his hardwood-floored, glass-walled, art-adorned eyrie that gazes down upon Sunset Boulevard, he has been Jackson’s eyes and ears in the movie-town since 1992. It is also easy to see why the Kiwi director has remained loyal to his Hollywood minder. Kamins is no mere facilitator or dealmaker; he is a great storyteller, who parses the madness of the film industry with wisdom and wry humour, and stood in the eye of the hurricane of the trilogy’s storm-tossed beginnings. There were times when the future of the project depended on Kamins’ gift for talking down dragons.

He openly admits the books had meant very little to him. ‘They were not, like, seared on my soul. I mean, I knew of them. But I was in no manner, shape or form an aficionado, or a hardcore fantasy fan for that matter.’

Rather than King Kong , Kamins is a ‘ Godfather -fanatic’. Film class at college had introduced him to films like The Grand Illusion , Klute and Rio Bravo . That is where his tastes lay. He believed in his client’s project without it having to be a religious experience.

Out of college, Kamins had climbed onto the lower rungs of the film industry, reaching the nascent home entertainment business at RCA Columbia at exactly the time his mentor Larry Estes began backing low-budget film productions, laying off theatrical and television rights while retaining the video rights.

Under that paradigm they backed Steven Soderbergh’s sex, lies and videotape , which had caused a stir at the Sundance Film Festival. Every independent theatrical distributor had come running in. They ended up making a deal with Harvey Weinstein.

Using this business model, home video specialist LIVE Entertainment would back Reservoir Dogs and begin Tarantino’s journey toward the sun. Another promising indie named New Line Cinema also began to see significant profits care of its home entertainment investments.

It was while at the now defunct talent agency InterTalent, a few rungs higher in his career, that Kamins’ boss, Bill Block, couldn’t get a ticket to the Batman Returns premiere. Tim Burton’s shadowy superhero sequel was the seen-to-be-seen-at golden ticket of the week. In his frustration Block had glanced over the many invites, requests and pleas for representation yet to be cleared from his desk and a letter caught his eye. It came from an attorney. ‘Hey, I have this client. He’s going to be in LA. He’s holding a screening of his new movie.’

Block walked down the corridor and into Kamins’ office. ‘I’m going to this screening and you’re coming with me.’

It was called Braindead .

Jackson was stopping in Los Angeles on his way back from Cannes, where he had been endeavouring to sell the distribution rights to his great ode to the flinging of viscera. The film that a mesmerized Guillermo del Toro once claimed made ‘Sam Raimi look like Yasujiro Ozu’. While in town, Jackson was hosting a screening at the Fine Arts Theatre on Wilshire Boulevard. Despite clashing with the big-budget antics of The Penguin and Catwoman, every agency in town was sending someone.

Kamins was impressed at the inventive use of effects in what was clearly a ‘modestly budgeted’ horror film. He certainly had never seen a hero lawnmower his way through a zombie horde. Indeed, it was the film’s sense of humour that spoke to him. The director was winking at the audience, egging them on. ‘Can you believe this level of madness?’

Kamins was reminded of the Marx Brothers.

‘I think that Peter unwittingly tapped into that same sense of anarchy,’ he says. ‘“I’m going to do things my own way. I’m going to challenge norms.” And I don’t know that I even understood it that clearly at the time. But it resonated for me.’

There was a spate of lunches for Jackson that week. Held at jazzy, star-spotted joints like Spagos or Chasens where the would-be agents reeled off a blur of inane advice. Oh, you should do a Friday the 13th . Oh, you should do a Tales from the Crypt . Oh, you should do a Freddy movie. All they could see was Braindead the horror movie, Jackson the New Zealand Sam Raimi.

Theirs was the last lunch of the week. And Kamins took a revolutionary approach. ‘I remember asking him, “Well, what do you want to do?” And he said, “Well, Fran and I are working on this project about matricide. About these two girls growing up in New Zealand, a true story …”’

It was called Heavenly Creatures .

The next week, Kamins’ phone rang. Jackson’s chirpy voice came on the line: ‘Fran and I have had a chat. We would like you to represent us.’

Kamins wasn’t the first agent-manager of Jackson’s career. Shortly after finishing Meet the Feebles , he had ventured to Los Angeles and found representation with a good-sized agency and a very good lawyer in Peter Nelson, who has stayed the course to this day (and would be another important figure in the many, many negotiations to come). Nelson had sent out the invitations to the Braindead screening with the objective of landing Jackson fresh representation. As he put it, the previous agency had ‘fallen asleep’.

Speaking to Jackson over lunch, Kamins was impressed by how purposeful and business-like was this young director. ‘For somebody who did not grow up here, but who clearly was a fan of movies and had aspirations to be a filmmaker, I was struck by how not -awed he was by the town. He had a fearlessness or a blindness to the reality of what he was walking into. All of which seemed to serve him really well.’

*

Heavenly Creatures changed everything. Heavenly Creatures got Jackson out of the horror ghetto where Hollywood would be happy to confine him. ‘Oh, he makes those low budget splatter movies that have some humour in them.’ Typecasting, Kamins could see, that didn’t project ‘a vision that he could do bigger films’.

Disney had offered him a supernatural rom-com called Johnny Zombie , which he wisely turned down. It was made by Bob Balaban as My Boyfriend’s Back in 1993, and swiftly forgotten thereafter.

He had so much more to him than Bad Taste .

Jackson followed Braindead by winning the Silver Lion for Best Direction at the Venice Film Festival. Head of the jury David Lynch had quickened to a queasy portrait of small-town murder where schoolgirls turned out to be the perpetrators not the victims. There were further festival awards to follow at Toronto and Chicago, and nine New Zealand Film and Television Awards.

‘There was a sophistication to Heavenly Creatures ,’ says Kamins proudly. ‘This was not a horror film in the traditional sense.’

Читать дальше