Lawrence Samuel was made as comfortable as possible, but his condition continued to deteriorate. Louisa stayed at the hospital to be near him, while the younger children were billeted at a nearby house with their Irish governess. Sometimes the family would drive out into the surrounding hills, where in the cool pine forests, loud with the rustle of the trees, the throbbing chorus of birdsong and the bubbling of the shallow, brownwater streams, Gerald was given a broader vision of the world of nature. Occasionally he was given rides on his father’s large bay horse, surrounded by a ring of servants in case he fell off. Not even the death of the horse, which fell down a cliff when Gerald suddenly startled it as it grazed with its feet tethered near the edge one day, could wean him off his burgeoning passion for the animal world.

On 16 April 1928, when Gerald was three years and three months of age, his father died of a suspected cerebral haemorrhage, and was buried the next day at the English cemetery at Dalhousie. Neither Gerald nor Margaret attended the funeral. Mother was entirely shattered.

Within the family there was a general feeling that Father’s premature death, at the age of forty-three, was brought on by worry and overwork. He had made a fortune as a railway-builder, but had fared less well when he turned to road construction, on one occasion undertaking to build a highway on a fixed-price contact, only to find that the subsoil was solid rock. His sister Elsie believed he had ‘worked himself to death’, and was told that at the moment he was taken ill he was ‘out in the heat of the midday sun supervising a critical piece of work on a bridge’. According to Nancy Durrell (who would have got it from her husband Lawrence), her father-in-law had quarrelled with the Indian partners in his business. ‘They apparently turned a bit nasty, and there was a very gruelling lawsuit, which he handled all by himself, he wouldn’t have a lawyer. But he got overexcited, and what exactly happened I don’t know, but in the end he had a sort of brainstorm, and he died rather quickly.’

In July 1928 Lawrence Samuel’s will was granted probate, and Louisa, now embarking on almost half a lifetime of widowhood, was left the sum of 246,217 rupees, the equivalent of £18,500 at the exchange rate of the time, or more than half a million pounds in today’s money. Financially enriched but emotionally beggared, she was left bereft: grieving, alone and helpless. So great was her despair that years later she was to confess she had contemplated suicide. It was only the thought of abandoning Gerry, still totally dependent on her love and care, that restrained her. Mother and child were thus bound together for ever in a relationship of mutual debt and devotion, for each, in their different ways, had given the other the gift of life.

‘When my father died,’ Gerald was to recall, ‘my mother was as ill-prepared to face life as a newly hatched sparrow. Dad had been the completely Edwardian husband and father. He handled all the business matters and was in complete control of all finances. Thus my mother, never having to worry where the next anna was coming from, treated money as a useful commodity that grew on trees.’

Gerald himself was seemingly unscathed by the family tragedy:

I must confess my father’s demise had little or no effect upon me, since he was a remote figure. I would see him twice a day for half an hour and he would tell me stories about the three bears. I knew he was my daddy, but I was on much greater terms of intimacy with Mother and my ayah than with my father. The moment he died I was whisked away by my ayah to stay with nearby friends, leaving my mother, heartbroken, with the task of reorganising our lives. At first she told me her inclination was to stay in India, but then she listened to the advice of the Raj colony. She had four young children in need of education – the fact that there were perfectly good educational facilities in India was ignored, they were not English educational facilities, to get a proper education one must go ‘home’. So mother sold up the house and had everything, including the furniture, shipped off ahead, and we headed for ‘home’.

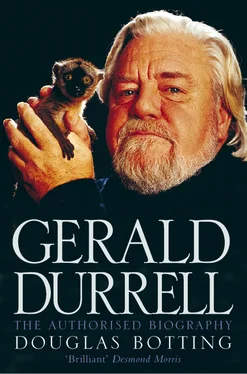

Mother, Margaret and Gerald took a train that bore them across half the breadth of India to Bombay, where they were to stay with relatives while they waited for the passenger liner that was to carry them, first class, to England. So Gerald sailed away from the land of his birth, not to return till almost half a century had gone by and he was white-haired and bushy-bearded. Like most of the other children on board, he was a good sailor – unlike the grown-ups. ‘Two days out,’ he wrote in his unpublished memoir, ‘we were struck by a tumultuous storm. Huge grey-green waves battered the ship and she ground and shuddered. All the mothers immediately succumbed to sea-sickness, to be followed very shortly by the ayahs, who turned from a lovely biscuit brown to a leaden jade green. The sound of retching was like a chorus of frogs and the stifling hot air was filled with the smell of vomit.’

The reluctant crew were forced to take charge of a dozen or more children of around Gerald’s age. Twice a day the children were linked together by rope like a chain gang, so that none of them could fall overboard, and taken up on deck for some fresh air, before being taken back down again to play blind man’s buff and grandmother’s footsteps in the heaving, yawing dining saloon. One of the crew had a cine projector and a lot of ‘Felix the Cat’ cartoon films, and these were shown in the club room as a way of diverting the children during the long haul to Aden and Suez.

‘I was riveted,’ Gerald remembered. ‘I knew about pictures but I had not realised that pictures could move. Felix, of course, was a very simplistic, stick-like animal, but his antics kept us all enthralled. We were provided with bits of paper and pencils to scribble with, and while the others were scribbling I was trying to draw Felix, who had become my hero. I was infuriated because I could not get him right, simple a drawing though he was. When I finally succeeded, I was even more infuriated because, of course, he would not move.’

Whether it was a real live creature, or an animated image, or a drawing on a page, the child brought with him a passion and a tenderness for animals so innate it was as if it was embedded in his genes. In the years to follow, come hell or high water, this affinity was not to be denied.

So young Gerald came to a new home in a new country – and a new life without a father. The loss of the family’s patriarch was to have a profound effect on the lives of all the Durrell siblings, for, deprived of paternal authority, they grew up free to ‘do their own thing’, decades before the expression came into vogue.

TWO ‘The Most Ignorant Boy in the School’ England 1928–1935

The house at 43 Alleyn Park, in the prosperous and leafy south London suburb of Dulwich, now became the Durrell family home. It was a substantial house, befitting the family of a servant of empire who had made his pile, with large rooms on three floors and a big garden enclosing it. Before long Mother had installed Gerald’s Aunt Prudence, a butler and a huge mastiff guard dog that chased the tradesmen and according to Gerald devoured two little dogs a day. But the new house was vast, expensive to run, and haunted: one evening Mother saw the ghost of her late husband, as plain as day, smoking a cigarette in a chair – or so Gerald claimed.

Early in 1930, therefore, when Gerald was five, the family took over a large flat at 10 Queen’s Court, an annexe of the sprawling Queen’s Hotel, a Victorian pile stuck in the faded south London suburb of Upper Norwood. Mother’s cousin Fan lived here, along with other marooned refugees from the Indian Army and Civil Service, so for her the place felt almost like home. The family’s new abode was a strange, elongated flat in the hotel grounds. The entrance was through the hotel, but there was a side door which allowed access to the extensive garden, with its lawns, trees and pond. ‘The flat itself consisted of a big dining room cum drawing room,’ Gerald recalled, ‘a room opposite which was for Larry, then a small room in which I kept my toys, then a minuscule bathroom and kitchen, and finally Mother’s spacious bedroom. Lying in bed in her room, you could look down the whole length of the flat to the front door.’

Читать дальше