When he gets up the next morning he finds, to his intense annoyance, that the blennies must have been active at dawn, for a number of eggs have been laid on the roof of the catching pot. Which female is responsible for this he does not know, but the male is a very protective and resolute father, attacking the boy’s finger when he picks up the pot to look at the eggs.

The boy waits eagerly for the baby blennies to appear, but there must be something wrong with the aeration of the water, for only two of the eggs have hatched. One of the diminutive babies, to his horror, is eaten by its own mother, before his very eyes. Not wishing to have a double case of infanticide on his conscience, he puts the second baby in a jar and rows back down the coast to the bay where he caught its parents. Here he releases it, with his blessing, into the clear tepid water ringed with broom, hoping against hope that it will rear many multicoloured offspring of its own.

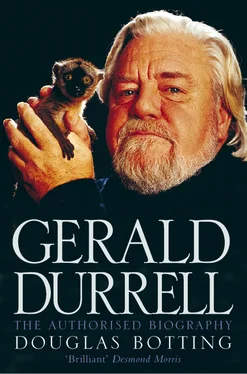

As a pioneer experiment in captive breeding, the blenny business is not an unqualified success. But it doesn’t matter. The blenny is not an endangered species. The sea round Corfu is stuffed with blennies. And there is plenty of time, for the boy, Gerald Durrell, is still only twelve years old, a whole life with animals stretches before him, and the summer blazes on for eternity.

PART ONE ‘The Boy’s Mad … Snails in his Pockets!’

ONE Landfall in Jamshedpur India 1925–1928

Gerald Malcolm Durrell was born in Jamshedpur, Bihar Province, India, on 7 January 1925, the fourth surviving child of Louisa Florence Durrell (nee Dixie), aged thirty-eight, and Lawrence Samuel Durrell, forty, a civil engineer.

When Gerald was older his mother told him something about the circumstances of his entry into the world. During the later stages of her pregnancy, it seems, she had swelled up to a prodigious degree, her enormous girth accentuated by her diminutive height, for she stood only five feet tall in her stockinged feet. Eventually she had grown so ashamed of her immense rotundity that she refused to leave the house. This annoyed her husband, who told her she ought to get out and about and go down to the Club, the social and recreational centre where all the local members of the British Raj used to congregate. ‘I can’t go to the Club looking like this,’ she retorted. ‘I look like an elephant.’ Whereupon Gerald’s father suggested building a howdah in which she could pass unnoticed, a flippancy which so annoyed her that she refused to speak to him for two days.

‘As other women have cravings for coke or wood shavings or similar extraordinary foods when they are in this state,’ Gerald was to record in an unpublished memoir about his Indian childhood, ‘my mother’s craving was for champagne, of which she drank an inordinate quantity until I was born. To this I attribute the fact that I have always drunk excessively, and especially champagne, whenever I could afford it.’

Gerald was by far the largest of his mother’s babies, which might explain why she had grown so huge during her pregnancy, and when he was fully grown he would stand head and shoulders not only above her but above his sister and two brothers, who were all almost as small as their mother. But his birth, when it came, was simple. ‘I slipped out of her like an otter into a pool,’ he was to write, relating what his mother had told him. The staff from the household and from his father’s firm gathered round to congratulate the sahib and memsahib on the arrival of their latest son. ‘All the Indians agreed that I was a special baby, and that I had been born with a golden spoon in my mouth and that everything during my lifetime would be exactly as I wished it. Looking back at my life, I see that they were quite right.’

Both of Gerald’s parents, as well as his grandfather on his mother’s side, were Anglo-Indians in the old sense of the term (not Eurasians, but British whites with their family roots in India) who had been born and brought up in the India of the Raj. His father had been born in Dum Dum in Bengal on 2.3 September 1884, and his mother in Roorkee, North-West Province, on 16 January 1886. Her father too had been born in Roorkee, and was six years old when the Indian Mutiny polarised the subcontinent in 1857.

Gerald’s family thus had little knowledge or experience of the distant but hallowed motherland of England. The depth of their association with India, which they regarded as their true home and native land, was such that when, many years later, Gerald’s mother applied for a British passport, she was to declare: ‘I am a citizen of India.’ Though Gerald was not to live long in India, its influence on his sense of identity was palpable, and at no point in his life was he ever to feel himself entirely English, in terms of nationality, culture or behaviour. For his three older siblings, who lived a good deal longer in India – Lawrence George (not quite thirteen when Gerald was born, and at school in England), Leslie Stewart (seven, and also about to go to school in England) and Margaret Isabel Mabel (five) – the sense of dislocation was even stronger.

Gerald’s mother was of pure Protestant Irish descent, the Dixies hailing from Cork in what is now the Irish Republic. It was to this Irish line that two of her sons, Gerald and Lawrence, were to attribute their gift of the gab and wilder ways. Louisa’s father, George Dixie, who died before her marriage, had been head clerk and accountant at the Ganges Canal Foundry in Roorkee. It was in Roorkee that she first met Lawrence Samuel Durrell, then aged twenty-five, who was studying there, and in Roorkee that the couple married in November 1910. ‘God-fearing, lusty, chapel-going Mutiny stock’, was how Gerald’s eldest brother Lawrence was to describe the family’s Indian roots. ‘My grandma sat up on the veranda of the house with a shotgun across her knees waiting for the mutiny gangs: but when they saw her they went the other way. Hence the family face … I’m one of the world’s expatriates anyhow.’

Louisa Durrell was an endearing woman, rather shy and quietly humorous, and totally dedicated to her children. She was so protective towards her brood that she was for ever rushing home from parties and receptions to make sure they were safe and sound – not without reason, for India was a dangerous place for children: her second-born, Margery Ruth, had died of diphtheria in early infancy, and Lawrence and Leslie were often ill with one ailment or another. Her husband adored her, but forbade her from involving herself in most of the usual routines and duties of a wife and mother of her era (including the daily practicalities of running a home and family, all of which were attended to by the native servants) because he felt she should observe the proprieties of her status as a memsahib of the Raj.

But though she was utterly devoted to her dynamic, patriarchal and largely conventional husband, and seemingly compliant to his every wish, there lay behind Louisa’s quiet, non-confrontational façade a highly individual and unusual woman, independent of spirit and not without fortitude, who unobtrusively went her own way in many things and quietly defied the rigid codes of conduct laid down for her sex in that era of high empire. As an Anglo-Indian, she was less mindful of her exalted status than the average white memsahib who passed her time in the subcontinent in a state of aloof exile. As a young woman she had defied convention and trained as a nurse, and had even scrubbed floors (unheard of for a white woman in India then). When her husband’s work took him up-country or out into the wilds, his young wife, along with their children, would go with him and rough it without complaint. When he was back in town, and out at the office or on a construction site, she would spend hours in the heat and smoke of the kitchen learning from cook the art of curry-making, at which she became very adept, and developing a taste for gin at sundown, though Lawrence Samuel made sure she limited herself to no more than two chota-pegs a day. It was probably from his mother that Gerald (like his two brothers) inherited his humour and the alcohol gene. But it was from his father that he inherited his bright blue eyes and hair type (full and flopping over his eyes) and his height, exceptional in an otherwise very short family.

Читать дальше