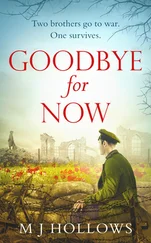

There was a loud crack, accompanied by the snap of breaking wood, which seemed to drag the sound out from its initial burst.

He turned to see a shape rushing towards them. He called out to Tom but it was too late. He just had time to reach for Tom and push him out of the way before an escaped barrel knocked into his back with force.

Tom fell to the ground with a cry as the metal-clad wood knocked into him. It carried on rolling past, and George was just about able to get out of its way, before it crashed against the brick wall of the dock house and burst open, spilling its contents all over the cobbles.

The coachman rushed to the back of his cart. The back plank had come undone, allowing the barrel to slip off the cart and run free. With the help of a few others, he managed to stop any more barrels falling off the cart and lashed them to the decking with some spare rope.

George ran over to Tom, sprawled on the cobble floor. Tom had been hit in the back and was lying face down. He feared the worst, but Tom just groaned and tried to roll over.

‘Don’t move, Tom. I’ll get help.’

Tom just smiled back at George as he always did and he pushed George away as he tried to check him for wounds.

‘Ah, don’t worry, George.’ He groaned as he sat up and put a hand to his back. ‘I’m all right, I’m all right.’

He finally accepted help but shook his head. George helped him up with a hand under his armpit and then dusted him down. There was a bit of blood on his forehead, but nothing on the rest of his body except for a bruise that would blacken over the next few days. George wet his handkerchief and handed it to Tom as he motioned for him to wipe his forehead. Seeing that George was taking care of Tom, the coachman got back up on his cart and led the horse away – any delay would cost him money.

‘Are you sure you’re all right?’ George asked.

‘Yeah. It was lucky you shouted,’ Tom said as he wiped the crusting blood from his forehead and winced at the pain. ‘I would have been stood stock still if you hadn’t. That shove helped too. I avoided most of the barrel.’ He stretched his back. ‘Still gave me a bloody great thump though. I’ll feel that one in the morning, no doubt. Let’s see what else they need us to do.’

He turned to walk away, but George grabbed him by the arm.

‘We should call it a day. You’ve had a nasty bump. That could be a head injury too,’ he said, gesturing towards Tom’s forehead again.

Tom shook his head and tried to hide another wince. The smile was back again. ‘There’s nothing wrong with my head,’ he said. ‘If we’re quitting work, do you think we should volunteer?’

George let go of his arm. ‘Come on, let’s go home. I’ve had enough for one day.’

‘I’m serious.’

George wiped the smile from his face, knowing it was doing him no favours in this situation.

‘I’ve been thinking about it a lot. No matter what else I do, I keep coming back to the same thought.’

George tried to show compassion and lighten the mood. ‘I know, you haven’t shut up about it since the other day.’

At that moment the dock master ran over to them and started shouting. He was an overweight man, his belly threatening to escape his waistcoat, and his hair was balding, leaving a sweaty pate of pink flesh.

‘What the hell is going on here?’ he shouted when he had got his breath back from the run. A frown crossed his face.

‘You.’ He pointed at Tom, who was still stretching his back, visibly uncomfortable at the pain. ‘What did you do? Why are you slacking?’

Tom shrugged. ‘I’m not,’ he said. ‘The cart’s full, and we’re going back for more.’

The dock master wasn’t appeased.

‘Don’t lie to me. I heard a commotion, what’s going on? If you’ve caused any damage…’

It was at that moment that he noticed the destroyed brandy barrel. It was a wonder he hadn’t seen it sooner, the stench of brandy was strong in George’s nostrils. The dock master’s eyes widened as he took in the broken wood and the precious cargo draining away through the cobbles.

‘You damaged the cargo,’ he said through gritted teeth.

‘What?’

The dock master grabbed Tom by the collar, even though Tom was a good foot taller than him.

‘Do you have any idea how much that barrel was worth? More money than you’ll ever have.’

‘What?’ Tom said again, unsure. ‘I didn’t do anything. You’re mad.’

‘Damn right I’m mad. How are you going to pay for that?’

George moved to help Tom, but couldn’t see how without angering the dock master further. Instead he tried to calm him down.

‘Tom didn’t do anything, sir. The tail board on the cart broke and the barrel rolled off. If you ask the coachman he will vouch for us.’ The coachman wouldn’t be back for a while, but at least it might buy them some time.

The dock master turned to George, still holding Tom by the collar.

‘Who asked you? As far as I know you’re just as much to blame as this idiot is.’

Tom used that moment to break free of the dock master’s grasp. With a lurch, he pushed the smaller man away with both hands. He moved backwards and tripped over a cobble, but thanks to his low centre of gravity, managed not to fall.

‘I didn’t break the barrel, sir. In fact, it almost broke me.’ As a gesture of goodwill, Tom checked the man over to make sure he wasn’t hurt. ‘Now, if you don’t mind, my friend and I would like to get back to work. There are plenty more barrels like that that need moving and if that doesn’t get done, then I guess you’ll lose even more money.’

The dock master trembled, in shock from Tom’s shove, then nodded.

‘Fine. I’ll chase that coachman for this. But if either of you lads does anything like this again, if you put one finger where it shouldn’t be, then I will make sure that you never work anywhere on these docks again.’

He walked away, his pace slightly quicker than a walk like someone trying to escape a confrontation with an enemy without drawing attention to himself.

‘Now get back to work,’ he called over his shoulder, as if it was his idea and not Tom’s.

‘That was close,’ Tom said, grabbing George by the arm and leading him away. ‘Come on, let’s get this over and done with.’

They went back to work, but before long the conversation had returned to the war.

‘Well now, I think they’ll take me,’ Tom said out of the blue, and George rolled his eyes at him, even though Tom wasn’t paying attention. ‘They need more men, they’ll take anyone that can hold a rifle at the moment. Besides, what have I got to lose? I’ve not got much here except my old mum. It’s gotta be better than this. Anything is better than this.’ He stopped and gestured at the barrel he had been rolling towards the new cart. The previous coachman hadn’t come back.

He stretched his back and groaned at the pain. Injuries were common around the dock, and Tom was lucky it hadn’t been worse. Every week one or more of the lads working on the dock ended up in a ward, or sometimes worse: a mortuary.

George grunted. It wasn’t so much that he agreed with Tom – he resented the fact that he had only thought about his mother and not his friends – but Tom had that way of getting you to see his point of view.

George thought about Tom leaving, and about working on the dock alone. It didn’t appeal to him. They made a good team.

‘If you go, Tom, I can’t go with you,’ he said.

‘Sure you can, if that’s what you want. Why not?’

‘For a start, I’m not old enough. You have to be nineteen before they’ll send you abroad, eighteen if you just want to stay at home doing something boring.’

Читать дальше