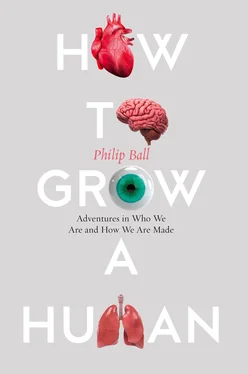

There was no rulebook to tell me how I should feel about my mini-brain. Certainly, I didn’t lie awake at night fretting over its welfare; this mass of tissue made from my skin didn’t take on the status of an individual. But I felt oddly fond of those cells, doing their best to fulfil a role in the absence of the guiding influence of their somatic source. 1There was a curious intimacy involved, a sense of potential that wasn’t present initially in the tiny chunk of arm-flesh excised and placed in a test-tube. This was more than a matter of cells subsisting; this was life in all its teeming, multiplying glory, spilling out from a paring of me.

My skin cells (fibroblasts) growing in a petri dish ( in vitro ) from a piece of skin tissue taken from my arm.

It’s hard not to invest the whole of biology with intentions, purposes, wants and needs, even though cells and simple organisms resemble automata responding without volition to the signals from their environment. (Some would say this applies to humans too.) That’s just how nature works.

Yet seeing these cells do their business in a petri dish is to recognize that life exists in doing. It is a process in which change is the only constant: change imbued with direction, more or less constrained onto a trajectory that evolution has guided and given what looks almost indistinguishable from a purpose, until death makes that change an inexorable slide into decay and entropic dissolution. There is no agreed scientific definition of “life”, but such a thing (if it is possible at all) would mean little if it fails to acknowledge this dynamic aspect, this interplay of predetermined pattern and historical contingency. It feels banal to say that my excised cells took on a life of their own, but what is so new and so remarkable about the science behind organoids is that we have the knowledge and power to influence the direction that life takes.

* * *

What really needs explaining is that my mini-brain was grown from a piece of my arm : in essence, from skin cells. That doesn’t sound like something that should be possible. Until barely more than a decade ago, most biologists thought so too. The discoveries that changed this view have transformed cell biology, raising all manner of medical possibilities for regenerating organs and tissues as well as opening up new avenues for basic research into embryology, development and conception. These discoveries and their applications are at the heart of this book.

But although these cell-transforming technologies have been celebrated, sometimes in breathless and hyperbolic terms, in the popular press, I’m not at all sure that their wider philosophical, one might even say psychic, implications have been acknowledged. Here is one of the profound things they say to us:

Every part of ourselves can potentially be turned into any other part of ourselves – including a complete self.

This, let me add, is more than science has yet proved. There is some small print attached, and further ingredients might be needed to fulfil the last part of the bargain. All the same, we are more plastic than we ever guessed. And that realization is in turn a culmination of medical advances and discoveries that have taken place over the course of the past century, which too we have processed only in the manner that we always process discoveries we don’t know how to think about. That’s to say, we have framed it around fears, fantasies and fiction.

For example: perhaps my “brain in a dish” immediately invokes visions of Frankenstein . And I pointed you also towards Brave New World , that re-envisioning of Mary Shelley’s tale for the age of industrialization and mass culture. These two novels remain today the favourite, off-the-shelf points of cultural reference for biomedical advances that unsettle and boggle the mind. But we are sent back to other speculative fictions by some of the possibilities that I have seen seriously and soberly discussed in the context of cell transformation and organoid growth. For example:

It may well be possible to grow a human brain in the body of a pig. One reason I find this so disturbing is that I still vividly remember first seeing the scene in Lindsay Anderson’s 1973 film, O Lucky Man! , where … well, if you don’t know it already, don’t let me spoil it for you.

It might be feasible to grow each organ of the human body separately outside the body itself in some sort of vessel ( in vitro ), and then surgically assemble them into a person – or enough of a person to be, let’s say, a personoid. And this is precisely how the first robots were made, in Karel Čapek’s 1921 play, R.U.R .

Philosophers, ethicists and neuroscientists are now compelled to debate what it could mean to create a full-grown human brain in a vat. Could it be conscious? Would it experience a self-contained interior “reality”? The pop-culture reference point here, which philosophers have embraced with nerdy delight, is of course the Matrix movies of the Wachowskis.

Let me make it clear that no researcher sees any prospect of these things happening in the near future, nor any good reason to try to make them happen. I will look at them more closely later, but my point here is not to tell rather shocking and thrillingly grotesque scare stories in a bout of bait-and-switch. What matters is that, confronted with so disorienting and disturbing a set of imaginable possibilities, we seem to need such stories in order to frame our thoughts. That in itself is worth considering. What motivates and shapes these narratives?

Underpinning them, I believe, is a consideration that might at first strike you as odd: We are not at ease with our own flesh .

But surely, you might say, we inhabit our own flesh? I’m putting those words into your mouth because they have a familiar ring to them – it doesn’t seem a strange thing to suggest. Yet such a phrase serves more to disassociate than to unite us with our flesh. We inhabit it? Like a person who inhabits a house? So what, then, are “we”? It’s the old Cartesian dualism: the separation of mind and body, or as some might have once said, of body and soul.

Yet of course we are not at ease in our own flesh! How we recoil from its routine functions, its excrescences and smells and fluids. How hard we try to remodel it, with what horror we watch its decrepitude. How we flock to watch movies like Hellraiser and Saw , or, at the more sophisticated end of the body-horror market, pretty much any of David Cronenberg’s early oeuvre. Gunther von Hagens, with his plasticized corpses, has made a career from an artful exploration of our horrified fascination; artists from Mark Quinn (who has sculpted with his own blood and the placenta of his baby son) to Marina Abramović have made what are often brave, painful and stomach-churning attempts to help us engage with our raw material.

There are many reasons for this ambivalence towards the somatic aspects of human existence, expressed repeatedly in all cultures in all ages: with piercings and tattoos, rituals of embalming and burial, elaborate taboos and the normative strictures of surgery. But the new sciences of culturing and transforming our cellular fabric confront us with perhaps the most fundamental challenge for our relationship with our flesh. They show us the ultimate in dismemberment: a reduction of the person to the cell.

Time was when we could dismiss that. Sure, cells are our building blocks, but no more or less so than proteins, atoms or quarks. If a chunk of our cellular material were removed, well, so what? It was no longer “us”, but a piece of waste, separate and dead, soon to be putrescent and doomed by microbes and entropy.

Читать дальше