The human landscape was not much more encouraging. Hutton’s family didn’t at first accompany him to Woolwich, and his new colleagues were a somewhat sorry crew. The Academy had existed for over fifty years, with a formal king’s warrant since 1741, but it was proving hard to get the setup right. Reform after reform had taken place. Initially it was meant as a sort of regimental university, providing lectures to anyone in the Royal Artillery who chose to attend: officers, NCOs, cadets, all those associated with the regiment. A series of mid-century reforms had given it a more manageable role as a sort of superior school for the Royal Artillery cadet corps. There was now an inspector-of-studies, with military rank, to look after the daily running of the Academy, to oversee the curriculum and make sure it was being delivered. Above him stood the Lieutenant-Governor, who reported to the Board of Ordnance and its Master-General. (The Ordnance, by the way, was not strictly speaking part of the Army: it was structured and governed separately, which goes some way to account for the uniqueness of its Academy.)

Some of the teaching staff had never accepted the changes to the style of the institution, or the inspector’s attempts to regulate what was taught and how it was taught; possibly they preferred the idea of themselves as university lecturers to that of schoolteachers. The chief master, Allen Pollock, had all but declared war on the management, doing everything he could to make the inspector’s task difficult. In principle he taught the prestigious subject of fortification and artillery. In practice he increasingly tended to teach absolutely nothing. He lived miles away from Woolwich without ever receiving permission to do so, and it was his habit to appear literally hours late for his lessons, then waste more time shuffling his books and his papers. For every adjustment to his teaching duties he demanded a direct written order.

There were also masters for French, dancing, fencing and ‘classics, writing and arithmetic’. The first two struggled to command the respect of the cadets – to put it delicately – while the last, a Reverend William Green, followed Pollock’s lead in calculated awkwardness.

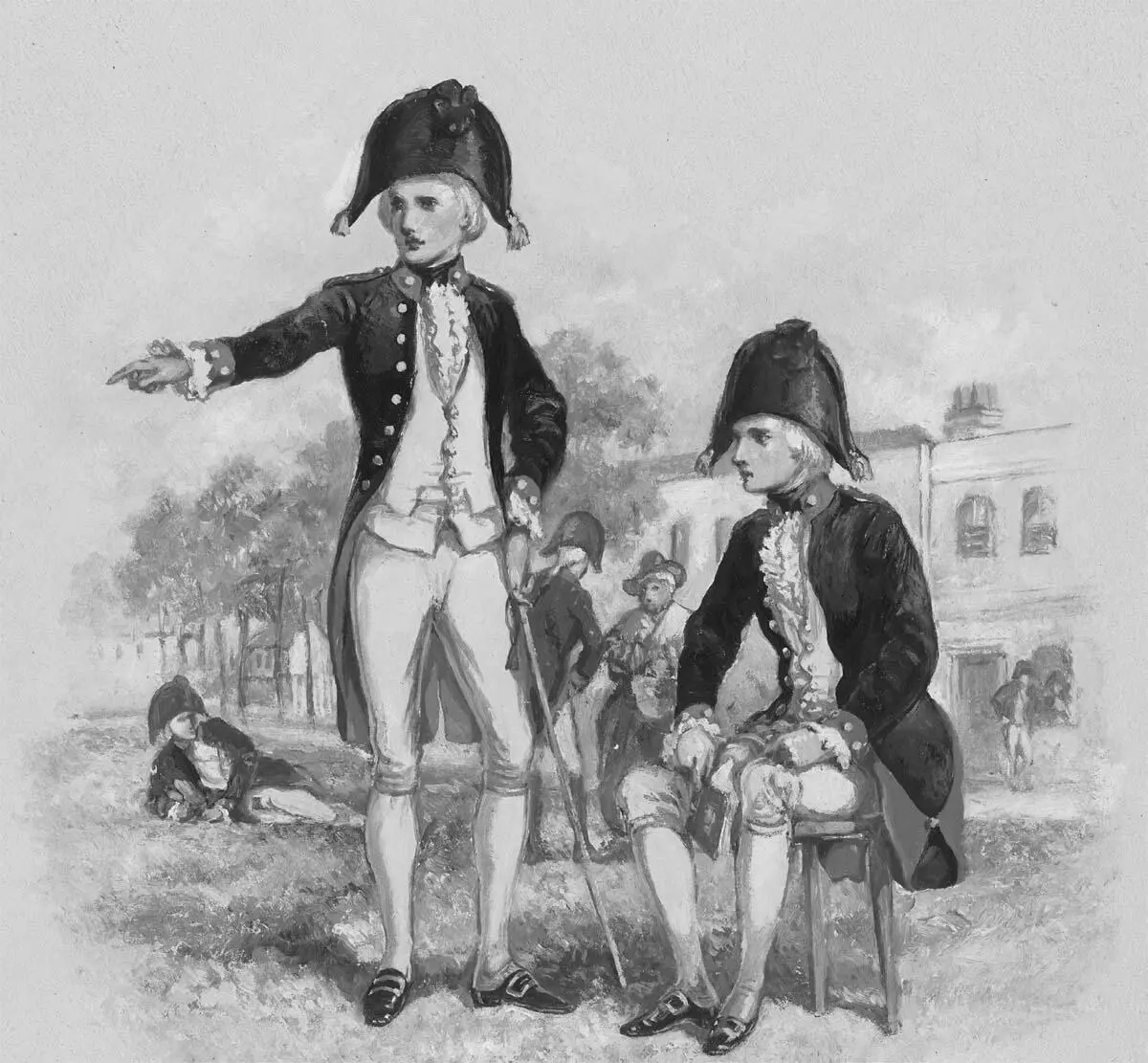

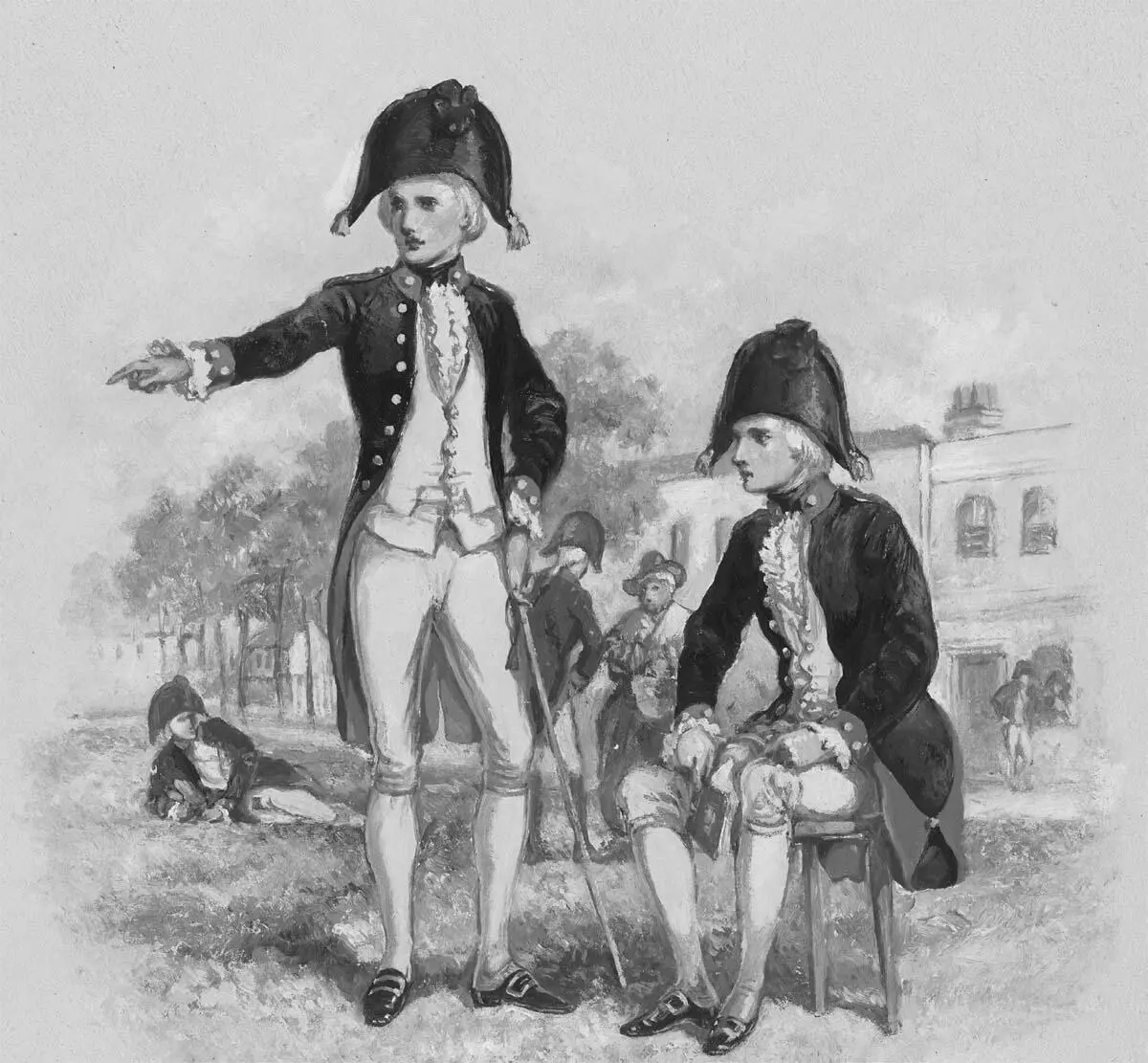

Gentlemen Cadets.

Hutton would have learned at least some of this over the summer, while his new house was being repaired and he was finding his feet after the upheaval of his move from the North. When the boys arrived after the summer recess and the actual teaching began, it may have been something of a relief. The cadets, numbering about fifty, were a well-dressed body of young men with a rather splendid uniform: blue coats trimmed with scarlet and gold; lots of lace, hair neatly queued and powdered.

They may have looked genteel, but they ranged in age from twelve to about nineteen, and there were predictable problems with their behaviour. Some ingratiated themselves with the masters, sending home for hams, hares, pheasants and other little gifts that might smooth their passage through classes and exams. Others indulged a tendency to riot. Orders and letters from the governor remarked again and again on matters of discipline, expressing futile outrage and lamely prohibiting misdemeanours after they had taken place. Cadets must not ill-use the masters, must not treat them with disrespect or insult them. They must not disrespect their superior officers, nor use indecent or immoral expressions. They must not wilfully destroy fixtures, bedding, furniture, utensils or windows, nor must they force locks or open or spoil the desks of the teachers or other staff. They must not ‘nasty the walls or chimneys’. They must not leap or run over the desks, nor climb out over the walls at night.

As the crimes escalated, so did the punishments. (‘The first Cadet that is found swimming in the Thames shall be taken out naked and put in the Guard-room.’) We read in mid-century accounts of solitary confinements, bread-and-water diets, imprisonments in a dark room, degradations and a few exemplary expulsions. In the long run, things improved, but outbreaks of quite serious violence remained more frequent than anyone could have wished. The constant presence of a duty officer in the classrooms had little effect. There was continued noise, hallooing, shouting; there was window-smashing, and ‘pelting’ of the masters. A lieutenant lost the use of his middle finger. A cadet spent three years on the sick list after a prank whose details he permanently refused to specify but which he steadfastly described as a piece of ‘fun’.

Charles Hutton was suddenly a very long way from the genteel sons and daughters of middle-class Newcastle: the grammar school boys and girls taking advanced mathematics lessons; the private pupils paying a few guineas extra for dancing classes and a few more for the course of lectures on astronomy. Yet his orders required him to teach the cadets, and to teach them a demanding curriculum that ranged across pure and applied mathematics. Teach it he would. The theory classes were on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays. Professor Pollock – if he bothered to turn up – taught the boys his notions of fortification and artillery for three hours in the morning; in the afternoon Hutton took them for mathematics from three till six.

Facing about twenty-five of the older or cleverer boys, grouped at least notionally into four graded ‘classes’, he covered Euclid’s Elements of geometry, killing two birds by using algebraic explanations wherever possible. Trigonometry as applied to fortification and measuring, such as finding inaccessible heights and distances, and using logarithms for the calculations if needed. Conic sections (the shapes you get when you slice a cone using a plane). Mechanics with reference to moving heavy bodies (such as pieces of artillery): levers, pulleys, wheels, wedges and screws. The laws of motion with reference, naturally, to projectiles. Calculus – ‘fluxions’, in the Newtonian rather than the Continental style – and whatever uses could be found for it. Much of this would have been familiar stuff from his Newcastle classroom, but the style of teaching still made it an exhausting round.

As in any other Georgian classroom, the boys were mostly at their desks, called forward one at a time or in small groups. Each boy did some exercises, showed them to the teacher, copied them and the relevant section of the textbook out fair: and repeated that round for the whole three hours. For Hutton it might mean fifteen minutes with one cadet on calculus; fifteen minutes with another on Euclid. Then algebra, then logarithms, then something else. He also gave periodic lectures – virtually the only university-style lecturing still taking place at the Academy – on geography and the use of those favourite pieces of eighteenth-century teaching apparatus the terrestrial and celestial globes: two hours every other Wednesday.

When they weren’t in the theory classroom, meanwhile, the boys were instructed on the other days of the week in the practical arts of gunnery: loading and firing the artillery pieces, and pointing them in the right direction; exercises in hitting marks. Various other practical matters: transporting burdens by making pontoons, floats or bridges; mortars and their use; trenches and mines: how and where; the composition of gunpowder; the names of the parts of a gun. Casting and weights of artillery pieces and shot. Handling of stores.

As if that wasn’t enough, from 1778 a separate building was set up as a ‘military repository’. Here the boys were taught the finer points of handling the equipment: mounting and dismounting ordnance, crossing obstacles, and ‘overcoming by resourcefulness difficulties which did not arise in the ordinary routine’.

Читать дальше