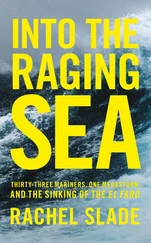

Three months after that simulation test, Villacampa and Haley were fired by the shipping company, along with two other seasoned officers, Captain Jack Hearn and Chief Mate Jimmy Armstrong. The official line was that they’d lost their jobs because illegal drugs had been found on one of TOTE’s ships.

In July 2012, US customs agents in Jacksonville saw a suspicious shipping container coming off El Faro ’s sister ship, El Morro . The box looked like it had been tampered with, maybe pried open after it had been sealed. Sure enough, a couple of the unlicensed crew—an ever-changing cast of characters hired through the union by the shipping company’s crewing manager—had stashed forty-seven kilos of cocaine inside it, a $3.5 million haul bound for the US market. After the seamen were busted in Jacksonville, the ship’s steward—a Puerto Rican named Danny, and another family member—were gunned down by a member of the drug cartel in a San Juan restaurant while Danny’s vessel was docked nearby.

That shipping containers had been used to transport contraband surprised absolutely no one. Roberto Saviano’s book on the Italian mafia, Gomorrah , offers a shocking example of the disturbing things people stuff in these nondescript steel boxes. In his book’s opening scene, a crate being loaded onto a ship in Naples accidentally opens midair and dozens of human corpses pour out of it and onto the ship’s deck. The dead immigrants had paid a lifetime’s worth of wages to the Mafia to have their remains repatriated to China; they were unceremoniously scooped back in and shipped according to plan.

No port authority has the resources to monitor what’s inside the hundreds of thousands of shipping containers crossing the oceans at any one time. Worldwide, approximately 1 percent of the boxes are actually opened and inspected. Drug dealers and arms brokers count on this fact to move their illicit wares around the globe; they build rare losses into their business plan. Because occasionally, someone gets caught.

Jack Hearn was captain of El Morro when the drugs were found, but how could he have known about them? Jacksonville Port was known as a major gateway for drugs traveling from South America to the US, especially since Puerto Rico’s economic collapse created a jobless, desperate population on the island. Of course TOTE’s ships occasionally carried contraband.

Hearn’s job was to deliver cargo and keep the vessel and crew safe. He’d done just that for more than thirty years. In that time, he’d watched the profession go from sextant to satellite. And in that time, the role of the captain evolved from running the ship to pushing paper. Hearn spent countless hours in his stateroom logging records, time charts, and data, managing the milk run back and forth to Puerto Rico. It was load and roll. Everyone was hustling. There wasn’t time for him to inspect every box that went on his ship and quiz every deckhand. Following the arrests, TOTE hired security guards to search crew as they came aboard.

TOTE’s firing of the four officers came as a shock to those working on the vessels. Haley wasn’t even on duty when the drugs were found. Two respected captains and two chief mates, all elders of the trade, were gone. With them, decades of knowledge and experience had been tossed out like yesterday’s garbage. The message was clear: no one’s job—on land or at sea—was safe.

TOTE became ruthless, driven to squeeze as much profit as possible out of an operationally expensive industry. Some mariners who worked for TOTE say that the company was making a significant profit at that time. The ships cost several million dollars, the labor, the berthing, the fuel, the endless maintenance, plus the insurance ( El Faro ’s hull and machinery were covered for $24 million)—all these big-ticket necessities cut into their bottom lines.

And lately, cargo prices had plummeted; worldwide, there was too much capacity, an abundance of ships, and not enough customers. Hanjin, one of the world’s largest shipping companies, filed for bankruptcy in 2016, leaving seventy-eight of its laden ships wandering the oceans in search of ports that would unload their goods without guaranteed pay.

Piracy also plagued the industry. Notorious waterways like the Malacca Strait (between Malaysia and Sumatra), the South China Sea, the Gulf of Aden (the entrance to the Red Sea), and both coasts of Africa teem with pirates looking for valuable cargo or, even better, officers to ransom. In late October 2017, six crew from a German container ship approaching a Nigerian port were reported kidnapped. In 2013, the World Bank estimated that the annual cost of piracy off the coast of Somalia ran somewhere around $18 billion.

Cyberattack posed another threat. Shipping is heavily dependent on computers for tracking vessels and complex logistics. Maersk, a global shipping giant based in Denmark, found its data held for a $300 bitcoin ransom (about $1 million at the time) by malware in June 2017. The attack cost the company approximately $300 million in lost revenue.

Compounding TOTE’s plight: Puerto Rico, the company’s cash cow, was collapsing. Islanders were fleeing the bankrupt territory, reducing demand for goods from the mainland. TOTE’s direct competitor in the Puerto Rican trade, Horizon Shipping, went bankrupt in early 2015.

Further, new environmental regulations were about to render TOTE’s old steamships obsolete.

In 2011, TOTE engaged a consultant to figure out how to run the company leaner. He immediately replaced long-standing managers and staff. Other positions were deemed unnecessary and eliminated. It appeared to those who worked on the ships that TOTE wanted younger officers and the cocaine bust seemed like an excuse to clear house.

TOTE may have had an ulterior motive for firing Captain Hearn: the old shipmaster had become a troublemaker. A few years before the drug bust, TOTE replaced El Faro with a new class of vessel in Alaska to meet environmental regulations. The old steamship was tied up in a Baltimore slip. Hearn had mastered El Faro in the icy Pacific Northwest for seventeen years, then was transferred to helm her sister ship El Morro in the warm waters between Jacksonville and Puerto Rico.

In his estimation, El Morro was an inferior ship, a rust bucket, seriously neglected while working herself to death in the corrosive Caribbean run. The hot, humid climate relentlessly gnawed away at her steel, leaving rusty tears streaming down her ancient hull.

Both El Faro and El Morro were nearly forty years old but to Hearn, El Faro was an old friend, superior to his current clunker. It ate at Hearn knowing that she’d been left to rot away in a Baltimore slip.

Hearn’s fondness for his ship wasn’t rare in the maritime world. Many people who work closely with boats think of them as living beings, complete with their own personalities and peccadilloes. Even something as unwieldy as a cargo ship can have ardent admirers.

In The Log from the Sea of Cortez , John Steinbeck wrote eloquently in 1951 of the intense bond we instinctively form with boats: “How deep this thing must be. The giver and receiver again; the boat designed through millenniums of trial and error by the human consciousness, the boat which has no counterpart in nature unless it be a dry leaf fallen by accident in a stream. And Man receiving back from Boat a warping of his psyche so that the sight of a boat riding in the water clenches a fist of emotion in his chest.”

Hearn felt that clench in his heart each time he thought about El Faro . He alerted TOTE to the fact that El Morro desperately needed major maintenance. He considered the ship unsafe. When he wasn’t satisfied with TOTE’s unresponsiveness, he informed the coast guard.

Читать дальше