In his perceptive Introduction to the 1960 anthology Best Secret Service Stories , editor John Welcome put his finger on a crucial distinction. ‘However skilfully the writer of a detective story juggles with settings and character, he is still bound to three essentials. There must be a crime (usually violent, usually murder), a search and a dénouement. Thus the detective story creates its own limitations. Whether it is set in the South Seas, Greenwich Village or the library of an English country house, it must still be worked out within that framework. Moreover, that it is in itself fundamentally a puzzle is another factor contributing towards artificiality, (The reader) is being compelled to read on not by the skill of the storyteller but by the urge to find a solution. The detective story is the big brother to the acrostic 7and the crossword. The writer of thrillers, on the other hand, knows no such limitations. He is a storyteller and he is at large …’

To further confuse matters, in 2002 in The Mammoth Encyclopedia of Modern Crime Fiction compiled by Mike Ashley (one of the most respected anthologists in the business) Ashley excluded thrillers from his truly mammoth work on the grounds that ‘whilst some crime fiction may also be classed as a thriller, not all thrillers are crime fiction’. For his purposes, Ashley defines crime fiction as a book which involves the breaking and enforcement of the law, which is fair enough, but then he also excludes spy stories and novels of espionage – on the grounds that they constitute such a large field they deserve a study in their own right and even though spying usually involves breaking someone’s laws.

Even excluding thrillers and spy stories, as well as stories involving the supernatural or psychic detectives and anything labelled ‘suspense’ or ‘mystery’ (when describing the mood rather than content of a story), and then only dealing with authors writing since WWII, Ashley’s splendid encyclopedia weighs in at almost 800 pages.

Does any of this soul-searching by people in the business (writers, editors, reviewers) over terminology really matter? Because the field of crime fiction, or what the Victorians would have called ‘sensational fiction’, is now so large – so popular – it probably does, at least if one is trying to make a point about a particular aspect or time period.

To keep it simple, let us say that the overall genre of crime fiction encompasses crime novels (which contain danger, a puzzle or a mystery centred on an individual or individuals, the outcome of which is resolved by more or less lawful means by characters who are usually law-abiding citizens or officers of the state) and thrillers where the perceived threat is to a larger group of people, a nation or a society and a solution is reached by heroic action by individuals taking action outside the law, usually having to deal with extreme physical conditions or an approaching deadline.

Paraphrasing Dorothy L. Sayers, in the crime novel it is what happened in the past (who did the murder? what motive did the murderer have? how did a particular cast of characters happen to come together?) which is important; in the thriller it is what is going to happen next.

A good dictionary will define a thriller as a book depicting crime, mystery, or espionage in an atmosphere of excitement and suspense, which could, of course, also define the crime novel – accepting that espionage is a crime, or it certainly is if you are caught. So perhaps, to quote Sayers again, it is all a question of emphasis. In the crime novel the emphasis is on the crime and its consequences. In the thriller the emphasis is on thwarting or escaping the crime or its consequences and the thriller usually requires a conspiracy rather than a crime.

The best shorthand definition of a thriller was probably provided by that author of superior spy fiction Anthony Price, when he reviewed Berkely Mather’s With Extreme Prejudice for the Oxford Mail in 1974. He summed up the book – and, succinctly, the genre as: ‘Action, pursuit, violence and villainy.’

P. G. Wodehouse is reputed to have called readers of thrillers ‘an impatient race’ as they long ‘to get on with the rough stuff’ and rough stuff, or action, is certainly more predominant in the thriller, often taking place in a hostile environment – at sea, under the sea, in the Arctic, or under a pitiless desert sun, sometimes cliff-hanging from the edge of a precipice. In keeping with Edgar Wallace’s ‘pirate stories in modern dress’ description (of which Margery Allingham would have approved – she was keen on pirates and treasure hunts), the exotic foreign location became a popular trait of the British thriller. More than that, it became a major component and though it would be too simplistic to say that crime novels happened indoors whilst thrillers happened outdoors, the concentration on action and ‘rough stuff’ thrills did often require a large, open-air canvas.

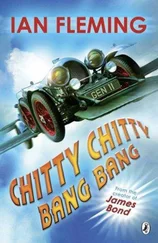

If the key building blocks of crime fiction are: plot, characters, setting, pace, suspense and humour (the latter may come as a surprise, but there is a long tradition of humour in British crime writing going back to the days of Wilkie Collins), then one can logically assign large blocks of plot, character, and suspense and smaller characteristics of setting, pace, and humour to the crime novel whereas the thriller’s foundation might be huge blocks of plot, setting, and pace, with smaller proportions of bricks devoted to characters and suspense and sometimes no humour at all. (Ian Fleming disapproved of the use of humour in thrillers, though many other writers found room for a wise-cracking hero.)

Once again, it comes down to a question of emphasis.

For the period under review here – 1953 to 1975 in Britain – our basic division of crime fiction into crime novel and thriller is a starting point only. Any assessment of crime fiction over the period 1993 to 2015, for example, would certainly require a different schema and to cover the entire history of crime writing just in Britain would produce a family tree with so many sprigs and branches it would resemble a Plantagenet claim to the throne.

Such an exercise would be an interesting challenge, but this is not the place. Even so, we must divide our sub-genres into sub-sub-genres, but hopefully not too many. If we can accept that the crime novel is an identifiable entity, and that we know one when we read one, then it is reasonably safe to assume that we can all recognise Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express as a crime novel, but Ian Fleming’s From Russia, with Love , which involves at least two murders on the Orient Express, as something else – it’s a thriller.

In another example of compare-and-contrast, 1954 saw the publication of two novels which were both initially billed by their publishers as ‘adventures’. The Strange Land by Hammond Innes had a lone hero figure in an exotic location (Morocco) struggling with a shipwreck, arid desert and mountainous terrain. Live and Let Die by Ian Fleming had a lone hero in an exotic location (America and the Caribbean) battling gangsters and communists as well as Voodoo and sharks. Both were clearly thrillers, but different types of thriller. The Innes was an adventure thriller , for want of a better term, and the Fleming was a spy thriller , albeit featuring a hero who did little actual spying and who acted more as a secret policeman, 8and not a particularly secret one at that.

Ten years later, that distinction was redundant as a new, more realistic type of spy story began to appear. Live and Let Die may have been one sort of spy thriller but The Spy Who Came in from the Cold was obviously of a different ilk.

Читать дальше