The Borough Press

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Publishers 2019

Copyright © Tracy Chevalier 2019

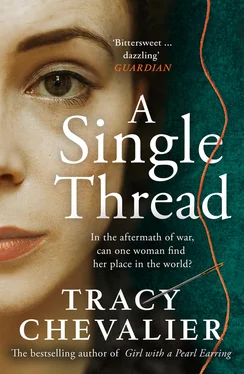

Cover design by Holly Macdonald © HarperCollins Publishers Ltd 2019

Cover photographs © Shelley Richmond / Trevillion Images (woman) and Shutterstock.com(needle and thread)

“Love Is The Sweetest Thing” Written by Ray Noble

Published by Range Road Music and Bienstock Publishing

Company o/b/o Redwood Music Ltd

Rights administered by Round Hill Carlin, LLC

Tracy Chevalier asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008153816

Ebook Edition © MARCH 2019 ISBN: 9780008153830

Version: 2020-05-06

For Morag

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also by Tracy Chevalier

About the Publisher

“SHHH!”

Violet Speedwell frowned. She did not need shushing; she had not said anything.

The shusher, an officious woman sporting a helmet of grey hair, had planted herself squarely in the archway that led into the choir, Violet’s favourite part of Winchester Cathedral. The choir was right in the centre of the building – the nave extending one way, the presbytery and retrochoir the other, the north and south transepts’ short arms fanning out on either side to complete the cross of the whole structure. The other parts of the Cathedral had their drawbacks: the nave was enormous, the aisles draughty, the transepts dark, the chapels too reverential, the retrochoir lonely. But the choir had a lower ceiling and carved wood stalls that made the space feel on a more human scale. It was luxurious but not too grand.

Violet peeked over the usher’s shoulder. She had only wanted to step in for a moment to look. The choir stalls of seats and benches and the adjacent presbytery seats seemed to be filled mostly with women – far more than she would expect on a Thursday afternoon. There must be a special service for something. It was the 19th of May 1932; St Dunstan’s Day, Dunstan being the patron saint of goldsmiths, known for famously fending off the Devil with a pair of tongs. But that was unlikely to draw so many Winchester women.

She studied the congregants she could see. Women always studied other women, and did so far more critically than men ever did. Men didn’t notice the run in their stocking, the lipstick on their teeth, the dated, outgrown haircut, the skirt that pulled unflatteringly across the hips, the paste earrings that were a touch too gaudy. Violet registered every flaw, and knew every flaw that was being noted about her. She could provide a list herself: hair too flat and neither one colour nor another; sloping shoulders fashionable back in Victorian times; eyes so deep-set you could barely see their blue; nose tending to red if she was too hot or had even a sip of sherry. She did not need anyone, male or female, to point out her shortcomings.

Like the usher guarding them, the women in the choir and presbytery were mostly older than Violet. All wore hats, and most had coats draped over their shoulders. Though it was a reasonable day outside, inside the Cathedral it was still chilly, as churches and cathedrals always seemed to be, even in high summer. All that stone did not absorb warmth, and kept worshippers alert and a little uncomfortable, as if it did not do to relax too much during the important business of worshipping God. If God were an architect, she wondered, would He be an Old Testament architect of flagstone or a New Testament one of soft furnishings?

They began to sing now – “All ye who seek a rest above” – rather like an army, regimental, with a clear sense of the importance of the group. For it was a group; Violet could see that. An invisible web ran amongst the women, binding them fast to their common cause, whatever that might be. There seemed to be a line of command, too: two women sitting in one of the front stall benches in the choir were clearly leaders. One was smiling, one frowning. The frowner was looking around from one line of the hymn to the next, as if ticking off a list in her head of who was there and who was not, who was singing boldly and who faintly, who would need admonishing afterwards about wandering attention and who would be praised in some indirect, condescending manner. It felt just like being back at school assembly.

“Who are—”

“Shhh!” The usher’s frown deepened. “You will have to wait .” Her voice was far louder than Violet’s mild query had been; a few women in the closest seats turned their heads. This incensed the usher even more. “This is the Presentation of Embroideries,” she hissed. “Tourists are not allowed .”

Violet knew such types, who guarded the gates with a ferocity well beyond what the position required. This woman would simper at deans and bishops and treat everyone else like a peasant.

Their stand-off was interrupted by an older man approaching along the side aisle from the empty retrochoir at the eastern end of the Cathedral. Violet turned to look at him, grateful for the interruption. She noted his white hair and moustache, and his stride which, though purposeful, lacked the vigour of youth, and found herself making the calculation she did with most men. He was in his late fifties or early sixties. Minus the eighteen years since 1914, he would have been in his early forties when the Great War began. Probably he hadn’t fought, or at least not till later, when younger recruits were running low. Perhaps he had a son who had fought.

The usher stiffened as he drew near, ready to defend her territory from another invader. But the man passed them with barely a glance, and trotted down the stairs to the south transept. Was he leaving, or would he turn into the small Fishermen’s Chapel where Izaak Walton was buried? It was where Violet had been heading before her curiosity over the special service waylaid her.

Читать дальше