Copyright

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.4thEstate.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc in 2015

This eBook edition published by 4th Estate in 2017

Copyright © Elizabeth Day, 2015

Elizabeth Day asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008221751

Ebook Edition © July 2017 ISBN: 9780008221768

Version: 2019-03-08

To Emma – here’s one for the rogue

Contents

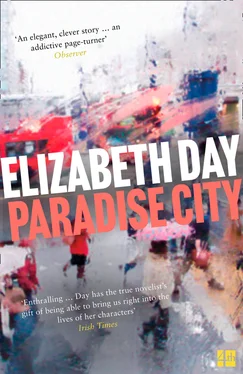

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

HOWARD

ESME

CAROL

BEATRICE

Howard

Esme

Carol

Beatrice

Howard

Esme

Carol

Beatrice

Howard

Esme

Carol

Beatrice

Howard

Esme

Carol

Beatrice

Howard

Esme

Carol

Beatrice

Howard

Esme

Carol

Beatrice

Howard

A Note on the Author

Keep Reading

About the Publisher

HOWARD

He loved hotels. The warm swish of the automatic doors. The careful neutrality of the carpets, swept with the indentations of that morning’s vacuuming. The bright smile of the receptionist, the way her make-up acted both as deterrent and encouragement. He loved the apples in glass bowls, although he had eaten one once and been disappointed by its mustiness, the slight furry staleness that he can taste – even now – on the back of his tongue. He loved the furtive glances across lobby armchairs, the reassurance of anonymity, the cocoon of safety offered by the standardised semi-luxury of faux leather and freshly spritzed white orchids in pots.

He loved the illicit meetings: the flirtations between adulterous couples, the City insider imparting information, the journalist who is talking to a grey man of indistinct appearance, jotting down notes. He loved the hushed business, the suggestive smiles, the fountain pens proffered when he has to tick a box for a morning newspaper or sign for ‘any additional expenses, if you wouldn’t mind, sir’. He loved it all.

And today, now, on this particular morning, he can feel a benign calm wash over him with the first step he takes inside the Mayfair Rotunda; with the first slight pressure of the tip of his leather-soled bespoke Church’s shoes on the marbled floor, he senses it. He breathes in an air-conditioned lungful, allows his Italian leather overnight bag to be taken from him by gloved hands, and strides across the floor.

‘Nice to see you again, Sir Howard,’ says the receptionist. He squints at her name-badge. ‘Tanya’, it reads, in sans serif font above two miniature flags – one of them is Spanish; the other he can’t make out. Eastern European, he shouldn’t wonder. Probably one of the former Soviet states. They were getting everywhere these thin, ambitious girls with their black hair and sharp little faces. He wasn’t sure it was a good thing. The last time he’d rung Le Caprice for a reservation, the girl at the end of the line had asked in a thick, guttural accent how to spell his name. He’d been going there for years.

Nevertheless, he is not one to pre-judge. He admires chutzpah, in the right place. He’s fond, too, of romanticising the immigrant experience, of reminding himself that, if it weren’t for the British, his forebears would have been gassed by the Nazis. The Finks, as they were then, would have been rounded up by jack-booted monsters if they hadn’t managed to get to England in 1933. And now look at them, he wants to say. And now …

He has never been to the death camps – can’t face the idea of them, let alone the reality – but his personal history remains a matter of considerable pride. On the one and only occasion he had been asked by the BBC to take part in a current affairs discussion programme, he had supported the relaxing of border controls and received one of the biggest cheers of the night. Looking back, he wasn’t even sure why he’d said it. He voted Tory, for God’s sake.

He smiles at Tanya, dazzling her with his expensive teeth (veneers and whitening done by a dentist recommended to him by a minor Royal. He isn’t one to name names).

‘Thank you.’

‘You’re in your normal suite, Sir Howard.’

For a brief moment, he wants to weep with gratitude at this kindness, this foresight, this human generosity shown to him by a global corporation. He’s always been sentimental: easily moved to tears by charity television adverts with soulful-eyed children in hospital beds. But Tanya remembering his name has demonstrated – in a small, but significant gesture – that he is who he thinks he is; that his importance as a businessman is an acknowledged fact. He is reminded, by Tanya giving him his normal suite, by intuiting his needs, that he has made his way, that he has his own part to play in it all: in the oiling of cogs, in the handshakes that lead to the lunches that lead to the buying and selling that lead to the acquisition of influence, to the stake in governance that results in the eventual spinning of the world on its axis. He can make things work. At this, he is undoubtedly a success.

Here he is, then, Howard Pink (formerly Fink), a man with complete awareness of his status in life, confident in his opinions, blessedly certain of the rightness of his decisions. A man of fortune, yes, but also of distinction.

The financial press will insist on putting ‘self-made millionaire’ after the comma. Howard used to wear this as a badge of pride. These days, however, he can’t help but feel there is something patronising in the phrase, a sense among the blue-shirted City bigwigs that he is not quite of their sort. He has always found it magnificently ironic that men (and it is, by and large, still men) who revere money for the power it gives them dismiss the ownership of it unless it has been inherited.

Because, Howard thinks, as he turns towards the lift, isn’t it more impressive to have generated £150 million from nothing than to have been handed it on a plate by a doddery great-uncle with a baronetcy and a mouldy pile of National Trust stones? Isn’t it better, somehow, to have made one’s own way by selling clothes on an East London market stall, clothes sewn by his mother, God rest her soul, bent double over her Singer machine with pins in her mouth (he was for ever telling her not to put pins in her mouth. Did she listen? Did she bollocks), clothes that he took and marked up and pushed onto the unsuspecting hordes of Petticoat Lane Market? Wasn’t that more admirable? To have made a profit, to have ploughed it back into better stock, to have sold more, of better quality and at a higher price, and to have done this over and over again, with one canny eye always on the bottom line, until he owned Fash Attack, the fastest-growing chain of clothing shops on the British high street?

Читать дальше