Both armies in Indochina were now impelled by a new urgency, to achieve the strongest possible battlefield position in advance of negotiations. Navarre and his subordinates abandoned the seesawing predictions they had made since December, and expressed vacuous hopes of victory. Emboldened by the soldiers’ confidence, the Paris government dismissed out of hand a proposal from India’s leader Jawaharlal Nehru for an immediate Indochina ceasefire. It remains unlikely that the Vietminh would have accepted such a truce, but there it was: the French rejected a chance – the last conceivable chance – to retrieve their stakes from the table at Dienbienphu.

Far from Paris, amidst the red earthworks, scurrying jeeps and sporadic shellfire of that wilderness outpost in western Tonkin, the French discerned another unexpected development in the enemy camp. Conventional wisdom demanded that artillery should be deployed on reverse inclines, beyond immediate reach of the enemy. Yet Giap, making new rules, sited his howitzers on forward slopes, where their barrels looked down on de Castries’ positions, with sufficient reach to claw most. The guns remained nonetheless almost invulnerable to French counter-bombardment, because they were lodged in tunnels until dragged forward to fire. The plain of Dienbienphu lay a thousand feet above sea level; the loftiest French positions rose six hundred feet higher. Yet only five thousand yards away, the communists held a hill line with an average elevation of 3,600 feet. Giap’s artillery would soon be able to ravage every French movement.

De Castries’ guns and mortars stood in open pits, hideously exposed. A few dismantled eighteen-ton Chafee tanks were flown into the camp and reassembled, providing mobile firepower. But French officers began to understand that they faced an ordeal by bombardment such as few of their men had ever experienced. Increasingly lively communist shelling meant that few men on outlying positions could avail themselves of the joys of the camp’s two field brothels. By mid-February, though no serious Vietminh attack had taken place, 10 per cent of the garrison had already become casualties. Diminished availability of C-47s caused worsening shortfalls in deliveries of supplies and munitions.

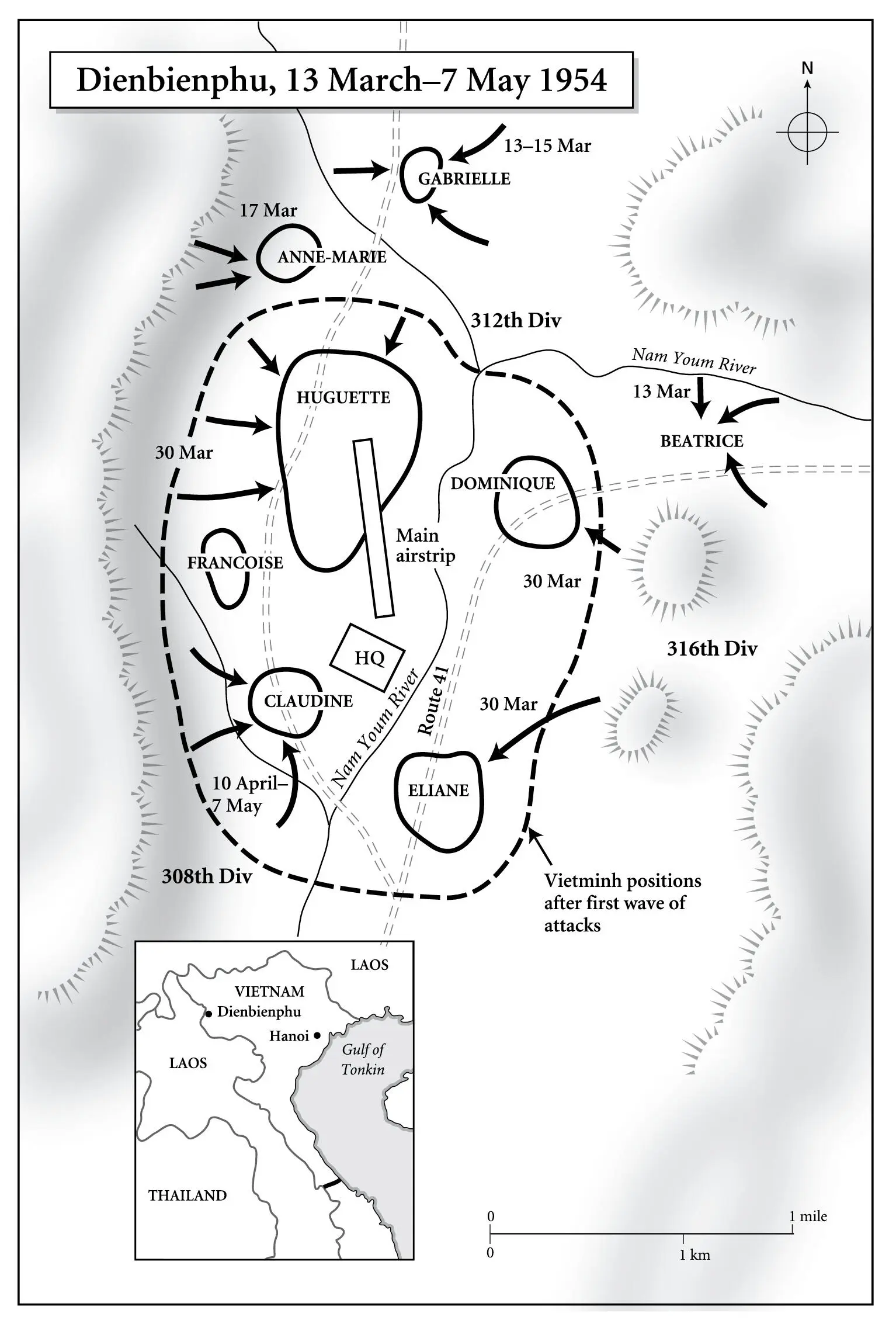

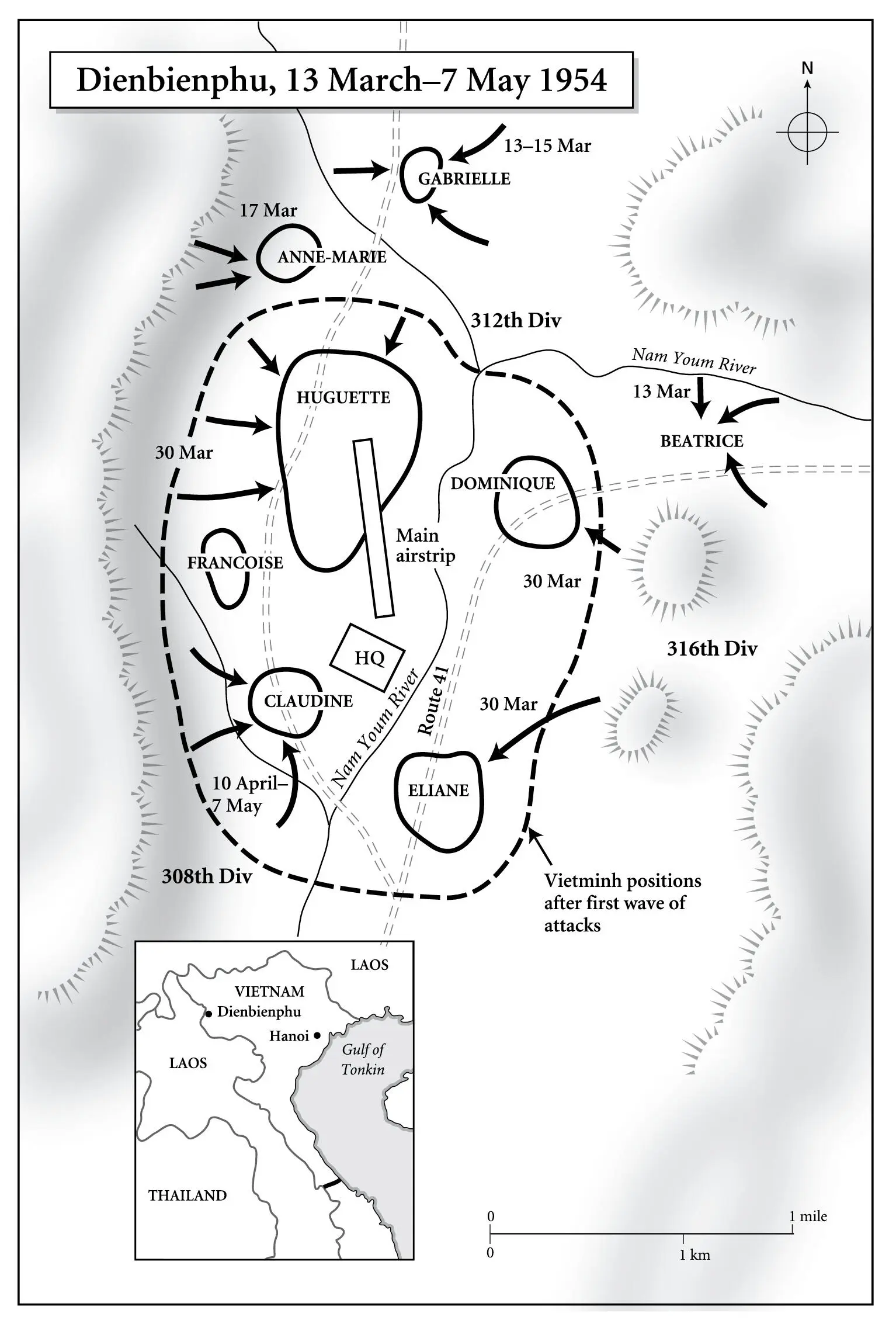

On 11 March, Vietminh artillery began to pound planes parked beside Dienbienphu’s runway. From the 13th every take-off and landing came under fire: airspace became unsafe below seven thousand feet. On the 12th René Cogny paid what proved his last visit: his plane departed amid a flurry of incoming shells, which the garrulous general was fortunate to survive. For weeks Giap’s troops had been digging, digging, digging on a scale such as no army had matched since the Western Front in World War I. One of them wrote: ‘The shovel became our most important weapon.’ They created around the perimeter a network of tunnels and trenches which provided both shelter and covered approaches. The French positions focused upon nine hills, to each one of which was allotted the beautiful name of a woman. Isabelle and Béatrice were deemed the strongest, though a newly-arrived para officer noted with dismay the vulnerability of their trenches and emplacements: the garrison might have fared better had its men spent the previous weeks digging as energetically as the besiegers.

On the morning of 13 March, Giap’s 312th Division was read a message from Ho Chi Minh, then joined in singing the Vietminh anthem. That afternoon, its soldiers mustered to attack Béatrice, the eastern French position, less than two miles from the airstrip. At 1705, as the defenders saw the Vietminh beginning to move, they were about to order defensive mortar and artillery fire when Giap pre-empted them. A storm of shells and heavy mortar bombs descended not only on Béatrice, but on widely dispersed targets throughout the camp, especially gun positions and headquarters. The bombardment was extraordinarily accurate, perhaps assisted by Chinese advisers among the Vietminh gunners, who had enjoyed weeks of leisure in which to calibrate ranges and scrutinise de Castries’ strongpoints. Vietminh patrols had reconnoitred with courage and infinite patience, crawling for hours in darkness amongst the French wire and trenches. In particular, they pinpointed the wireless antennae that marked command centres.

Pierre Langlais’ group survived only by a miracle. The colonel himself was standing naked beneath a pierced-fuel-drum shower when the barrage began, and ran unclad into his bunker, seconds before a shell exploded on its roof. He and his officers were left stunned in a chaos of fallen timbers, debris, earth and wrecked equipment; yet a second shell failed to explode. Elsewhere, a red and yellow fireball marked the eruption of the camp’s fuel and napalm dump. All but one of de Castries’ spotter aircraft were wrecked.

As the light faded on 13 March, defending commanders found themselves crippled. Many phone lines had been cut, and radios were working poorly in the usual evening atmospheric mush. The 450-strong Foreign Legion battalion holding Béatrice was understrength and short of officers. Commanders expected an attack, but not before nightfall. The Vietminh had excavated trenches within fifty yards of Béatrice’s perimeter, and from these their infantry stormed forward amidst a cacophony of cries and bugle calls, followed by detonations as bangalore torpedoes exploded beneath the defenders’ wire. Artillery dealt the deadliest blows: at 1830 a shell devastated Béatrice’s command post. As darkness deepened, the occupants of each bunker on the hill were obliged to fight isolated battles beneath the glow of flares. Some Legionnaires imposed heavy losses upon the attackers before succumbing. Within an hour, however, and exploiting a ruthless disregard for their own casualties, the Vietminh occupied positions deep inside the defences.

One French company commander continued to radio for gun support even as his trenches were overrun: ‘Right 100 … 100 nearer … 50 nearer … Fire on me! Les Viets are on top of us!’ Then there was only a hiss of static, as the voice fell silent. Col. Gaucher, who had gloomily predicted to his wife that he and his comrades were ‘destined for sacrifice’, was mortally wounded. Langlais was ordered to take over, but lacked phone and radio links. Soon after midnight the Vietminh secured control of Béatrice, having killed over a hundred defenders and captured twice as many, most of them wounded. Just a hundred men led by a sergeant-major made good their escape. When sunrise came at 0618 on the 14th, a strange silence overhung the battlefield, under a drizzle that turned to heavy rain. The camp’s medical staff emerged blinking and exhausted from their stifling bunker, having handled ten abdominal and ten chest cases, two cranials, fifteen fractures and fourteen amputations. Debris lay everywhere: blackened and burnt-out vehicles, smashed aircraft and equipment. A belated and futile air attack was launched against the Vietminh gun positions.

Then a wounded officer prisoner, Lt. Frédéric Turpin, staggered across from Béatrice to Dominique, bearing from the Vietminh the offer of a truce to evacuate casualties, which Cogny’s headquarters authorised. This was a shrewd psychological move by Giap, since it passed to the garrison responsibility for eight badly wounded men, and acknowledged his army as local victors. Turpin was fortunate enough to secure air evacuation to Hanoi. As for the men who remained, Pierre Rocolle wrote: ‘A stupor fell upon all those not engaged in urgent tasks. Officers and men could not stop asking themselves: “How could a Legion unit have been so swiftly overcome?”’ Cogny’s response was to reinforce the garrison with yet another battalion of paratroopers.

Читать дальше