Initially he thought it might be a straitjacket hugging him tightly. Perhaps the increasingly fractious relationship with his wife had finally reached a stage where his sanity had cracked, leading to an extreme psychosis demanding he be sectioned and confined in a small space?

He could still breathe easily enough, though he learned his breath smelt none too pleasant as he received instant feedback from the fabric pressed against his face. He tried to move his left arm, but this resulted in such searing pain that it made him gasp and brought tears to his eyes. He tentatively moved his right arm. He felt some gentle tingling but no pain. He pulled it free of whatever restricted it, reached up and removed the fabric membrane from his face.

Free of the first prison, he then faced a second containment. He’d been enclosed in something dark, hard and metallic. As far as he knew, even the most dangerous mental patients were not placed in metal boxes. At least, he didn’t think so, though he acknowledged he had limited knowledge of current UK mental health treatments.

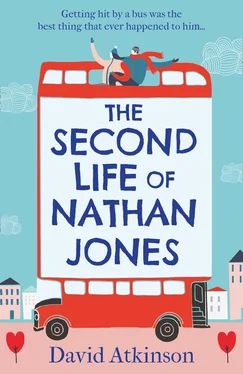

Unfortunately, at this point some feeling started to return to the rest of his body and he ached. Not the kind of soul-ache that you got from being desperately in love with someone, which he could still recall (just), but the kind of all-over body ache that occasionally accompanied a bad bout of the flu when it felt as though a little man was running around your body stabbing your extremities with a hot needle. In fact, it felt very much as if he had been hit by a bus. Then he remembered with a start of realisation that that was exactly what had happened.

He started to shout. However, his croaky, weak voice only produced a pathetic whimper. He tried to bang the sides of the metal container with his good arm, but this only made the smallest of sounds given the lack of space at his disposal.

Nathan then discovered that if he banged his bare heels off the bottom of the metal prison it made much more noise. He did this for a few seconds then gave up, exhausted.

Then he suddenly felt himself moving forwards. It felt like the start of a roller-coaster ride but without any of the delicious anticipation, and suddenly he slid out of the darkness into a harsh white light.

As he squinted into the brightness a face emerged and peered curiously at him. An angel perhaps? If so, she was nothing like those depicted in Hollywood movies. Her hair was black, her eyes were black, her clothes were black, her earrings were black, her piercings were black, even her lips were black – although her teeth were pearly white. She smiled at him and said, ‘Hello there.’

My full name is Klaudette Ainsworth-Thomas (yeah, I know). I woke up on my tenth birthday, decided enough was enough and made a monumental decision. The first person I had to tell? My mother.

‘Mum?’

Janice, my mum, could usually be found behind an ironing board. She ironed every day. Ironing was one of her many obsessions. If it got to 6 p.m. and there were no clothes left in the ironing basket she got all anxious and cranky and started to press things that had already been done, like my dad’s shirts or something random like the bedroom curtains. She had even been known to remove the cushion covers from the couch and press them on a low heat.

‘Mum?’

‘Yes, Klaudie?’ Now, there was another thing that annoyed me; even though my thoughtless parents had lumbered me with the triple-barrelled name from hell, they couldn’t even be bothered to use it properly and invariably shortened it to Scotland’s prevailing type of weather.

‘I’ve made a decision.’

‘That’s nice, dear.’

‘Mum, I’m serious.’

My mum put the iron down and stared at me. ‘Klaudie, you’re always serious, that’s your problem, you—’

‘No, Mum, that’s not my problem, that’s your problem. I am the way I am. I’ve decided that I’m sick of being called Klaudette, Klaudie and Klaudia, and I’m sick of Ainsworth-Thomas as well. From now on I’m only going to answer to the name Kat, K-A-T.’

‘K-A-T?’

‘Yep, Kat is much cooler and most of my friends call me that anyway.’

Mum returned to ironing her slippers. ‘That’s nice, dear.’

Despite my mum’s apathy I stuck to my guns and from that day on I only answered to the name Kat. Eventually everyone, including my parents and most of the teachers, adopted my new alias, the only exception being the assistant head at my crumbling Glasgow high school, Mrs Brock, who insisted on calling me Klaudette. As a result, I ignored everything she said for the next five years.

The only issue with this impasse happened to be that Mrs Brock also taught me history for two of those five years. History, therefore, didn’t turn out to be one of my strong points, not helped by the number of Harolds/Haralds mooching about in 1066.

The fault all lay with my mum. She’d met and married a John Thomas (yes, really) and they decided to join forces and hyphenate their names after they got married. I’d always thought someone who had grown up being called John Thomas would have had more awareness and sympathy about kids’ names instead of lumbering his only daughter with such a mouthful. He’d even managed to become a professor of social anthropology to avoid using his first name. Even his bank cards only had ‘Professor J Thomas’ printed on them.

As a youngster, before I had the presence of mind to change my name, I had a plump, lumpy body, a squished face and little self-confidence. I used to come home from school, go into my bedroom and slip into a Cinderella or Snow-White costume from my dressing-up box and prance up and down in front of the mirror pretending I lived a different life, using clothes as an emotional crutch, an image to hide behind. I still did.

I’ve always felt that there was a certain cruelty involved, growing up as an only child, especially with parents like mine, who were too wrapped up in their own obsessions to notice my issues. All parents should be obliged to have two or more children or none. In my opinion, having only one kid could lead to them growing up lonely – well, kids like me who had real problems making friends would, anyway. If I’d had a sibling, they would have played with me and banished some of my loneliness.

Yeah, but knowing you they would have hated you so that would’ve made things worse.

‘Things couldn’t have been much worse.’

Wanna bet?

When I get stressed I often argue with my inner self, usually out loud, which can bring me some weird glances from strangers. Well, weirder than normal. Reminiscing about my childhood usually raises my stress levels so I try not to.

Despite the problems in high school I left with some decent grades, much to the surprise of many of my teachers, especially Mrs Brock, and won a place at Napier University in Edinburgh to study nursing.

I couldn’t stand the thought of working in an office. I was a practical sort of person and initially believed that nursing would be a good option. I anticipated that it would provide a stimulating and fast-changing environment that would stop me getting bored. It didn’t.

My first placement in an adult surgical ward saw me dealing with patients who were either waiting for or recovering from an operation. The ward was chronically under-resourced (like so many others), which meant I felt used and abused by everyone, staff and patients alike. On my first eight-hour shift my mentor said, ‘Kat, the patient in room three needs some toast and tea. Can you get that for them?’

I rushed back to the nurses’ station after I’d finished. My mentor said, ‘Quick work, that. Can you change the two beds in room eleven, they’re covered in blood and vomit, and after that could you be a dear and nip down to the shops for some sandwiches for me and Elaine, the staff nurse, as we both forgot to bring anything in for lunch?’

Читать дальше