© Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum (NASM 9A13533)

By 1950, Arthur C. Clarke was a frequent guest on the BBC, explaining to British audiences the probable reason for the sudden increase in reports of UFO sightings, how humans might travel to other planets, and differing theories of a fourth dimension.

IN RAHWAY, NEW Jersey, the son of a garment worker from the Ukraine read about Clarke’s new book in an ad published in the latest issue of Astounding Science Fiction. The sixteen-year-old was fascinated by news articles about flying-saucer sightings and became intrigued by the possibility of life on other planets. But he knew little of the fundamentals of rocket science or planetary astronomy, so he ordered a copy of Interplanetary Flight via mail order from an address in the magazine.

Two decades after Clarke discovered The Conquest of Space in the bookstore window, it was his book that fell into the hands of another impressionable teenager. The high school senior, Carl Sagan, would later speak of reading Interplanetary Flight as the “turning point in my scientific development,” the moment that solidified the course of his life, leading him to become not only a noted astrophysicist but the most recognized popularizer of science in the United States during the last quarter of the twentieth century.

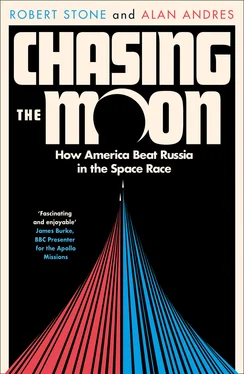

CHAPTER TWO CHAPTER TWO THE MAN WHO SOLD THE MOON (1952–1960) CHAPTER THREE THE NEW FRONTIER (1961–1963) CHAPTER FOUR WELCOME TO THE SPACE AGE (1964–1966) CHAPTER FIVE EARTHRISE (1967–1968) CHAPTER SIX MAGNIFICENT DESOLATION (1969) CHAPTER SEVEN THE FINAL FRONTIER (1970–1979) APPENDIX AFTER A FEW MORE REVOLUTIONS AROUND THE SUN PICTURE SECTION ACKNOWLEDGMENTS NOTES INDEX ABOUT THE AUTHORS ABOUT THE TYPE ABOUT THE BOOK ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

THE MAN WHO SOLD THE MOON CHAPTER TWO THE MAN WHO SOLD THE MOON (1952–1960) CHAPTER THREE THE NEW FRONTIER (1961–1963) CHAPTER FOUR WELCOME TO THE SPACE AGE (1964–1966) CHAPTER FIVE EARTHRISE (1967–1968) CHAPTER SIX MAGNIFICENT DESOLATION (1969) CHAPTER SEVEN THE FINAL FRONTIER (1970–1979) APPENDIX AFTER A FEW MORE REVOLUTIONS AROUND THE SUN PICTURE SECTION ACKNOWLEDGMENTS NOTES INDEX ABOUT THE AUTHORS ABOUT THE TYPE ABOUT THE BOOK ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

(1952–1960) CHAPTER TWO THE MAN WHO SOLD THE MOON (1952–1960) CHAPTER THREE THE NEW FRONTIER (1961–1963) CHAPTER FOUR WELCOME TO THE SPACE AGE (1964–1966) CHAPTER FIVE EARTHRISE (1967–1968) CHAPTER SIX MAGNIFICENT DESOLATION (1969) CHAPTER SEVEN THE FINAL FRONTIER (1970–1979) APPENDIX AFTER A FEW MORE REVOLUTIONS AROUND THE SUN PICTURE SECTION ACKNOWLEDGMENTS NOTES INDEX ABOUT THE AUTHORS ABOUT THE TYPE ABOUT THE BOOK ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

ON A THURSDAY evening in March 1952, viewers of NBC’s Camel News Caravan were introduced to a man who, in the next few years, would be celebrated as a national hero for ushering America into the space age, becoming his adopted country’s most widely recognized man of science. That only a decade earlier Wernher von Braun had overseen Adolf Hitler’s most ambitious weapons program is among the strangest and most confounding ironies of twentieth-century history.

It’s no surprise that von Braun’s affiliation with the Third Reich was not mentioned on the evening of his national TV debut. The handsome forty-year-old wore a tailored double-breasted suit and might have been mistaken for a crusading district attorney in a Hollywood film noir. But in no screen thriller did a DA ever speak in such a distinctly Teutonic accent or display the fantastic props that von Braun held onscreen. Viewers were told that these were models of space vehicles that would transport humans into the cosmos within a few years and bring an end to threats from Iron Curtain nations around the globe. Von Braun was on TV to launch a nationwide publicity campaign for the mass-circulation magazine Collier’s and, in particular, its latest issue, with a cover that proclaimed, MAN WILL CONQUER SPACE SOON!

In the spring of 1952, television sets were a fixture in one out of every three American households, an increase of 200 percent in the past twenty-four months. The new medium’s first users were predominantly upper-middle-class families living near cities with network-affiliate stations. For most of these viewers, von Braun’s spaceships were not a new sight. Adventure series such as Tom Corbett, Space Cadet and Captain Video were already competing against small-screen Westerns to capture the imaginations of young audiences. But von Braun’s NBC appearance that evening was intended for their parents, many from the generation of recent war veterans who were redefining America as it assumed its position as a global economic and military superpower. Indeed, the editorial introducing the new issue of Collier’s delivered an urgent Cold War warning: If the United States did not immediately establish its dominance in space, it would lose this high ground to the Soviet Union. Not only was America’s destiny in outer space but the nation’s security depended on mastering the science and technology to get us there.

Collier’s readers were introduced to von Braun as the technical director of the U.S. Army’s Ordnance Guided Missile Development Group. “At forty, he is considered the foremost rocket engineer in the world today. He was brought to this country from Germany by the U.S. government in 1945.” Further details about his wartime work were carefully omitted. He was pictured at the head of a table next to his first tutor and mentor in rocket research, Willy Ley. Shortly after the Peenemünde team arrived in the United States, Ley had cautioned friends to be wary of von Braun’s seductive charisma. By the early 1950s, von Braun’s charm, as well as his considerable political savvy and innate talent to inspire, had worked magic on his former enemies.

This wasn’t the first meeting on American soil of the two former colleagues. It was on a December evening in 1946 that Ley and von Braun had looked each other in the face for the first time in more than a decade and a half. Their post-war experiences in their adopted country had differed dramatically. Ley was the son of a traveling salesman; von Braun had been born into privilege, an aristocrat whose father was a politician, jurist, and bank official. Von Braun grew up with a sense of entitlement, which, when combined with his innate charisma, effortlessly opened doors. Physically, he could have been mistaken for a matinee idol; Ley once described von Braun’s appearance as “a perfect example of the type labeled ‘Aryan Nordic’ by the Nazis.” In affect and appearance, Ley, on the other hand, personified the “absentminded professor” stereotype. He wore thick-lens eyeglasses and spoke with a heavy accent, which peppered a discussion about UFOs with references to “flyink zauzers.” Nevertheless, Ley was a talented communicator with an ability to convey his curiosity and fascination about scientific subjects to audiences, which found his passions infectious. Unfortunately, he was less successful when attempting to find rocketry-related work in the United States in spite of his expertise, while von Braun charmed his way into new opportunities.

Their reunion had occurred when von Braun made his first visit to New York City, to attend an American Rocket Society conference, accompanied by his entourage of military minders. The presence of von Braun’s escort didn’t prevent Ley from extending an invitation to dinner at his apartment in Queens. Over glasses of wine, the two men talked until nearly 3:00 A.M., catching up on fifteen years of history during a discussion Ley later described as both tense and informative. Von Braun revealed the history of the Nazi rocket program and how he had come to lead it. However, he was less forthcoming about some crucial details that became more widely known only decades later.

Читать дальше