1 ...8 9 10 12 13 14 ...24 Shortly after V-E Day, it appeared that Lasser’s fortunes in Washington might be improving, as memory of his ridicule in the House began to fade. The Truman administration asked him to assist with the rebuilding of Europe under the Marshall Plan, offering him a position as a consultant to the secretary of commerce. Ironically, at nearly the same moment that American military and intelligence officers were quietly obscuring the past histories of former Nazi Party engineers, David Lasser’s political opponents began circulating false rumors about his alleged past association with subversive political organizations, in an effort to tarnish his reputation. They questioned his loyalty and argued that his “contrary views” posed a serious security risk.

Lasser was incredulous at the coordinated smear campaign. “I kept asking myself, what kind of government would do these things? What kind of people were we that this sort of thing happened?” Despite vigorous support from prominent politicians, the accusations and rumors effectively blacklisted Lasser from any further government employment. Far less renowned than the Hollywood Ten or writers like Howard Fast or Arthur Miller, David Lasser, one of the country’s first space advocates and the author of The Conquest of Space, became one of the first victims of the Red Scare.

© Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division

The Conquest of Space author David Lasser (center) and a fellow labor organizer meet with first lady Eleanor Roosevelt in Washington. Not long afterward, Lasser was ridiculed on the floor of the House of Representatives as “a crackpot with mental delusions that we can travel to the Moon!”

The War Department’s decision to bring scientists and engineers from Hitler’s Third Reich to work for the U.S. government did not go unopposed. Prominent physicists such as Albert Einstein and Hans Bethe as well as former first lady Eleanor Roosevelt criticized Operation Paperclip. But the larger looming reality of the Soviet Union’s brutal domination of Eastern Europe, legitimate fears of domestic espionage, and reports of a possible Russian nuclear-weapons program silenced most public resistance to the program. No congressmen delivered speeches questioning whether the German scientists posed a security risk or held contrary political views. Instead, the White House asked the Department of Commerce to issue reports that would explain to ordinary Americans how their daily lives would benefit from wondrous German technological breakthroughs in food preparation and the manufacture of cheaper, stronger clothing, such as run-free nylons and unlimited yeast production.

DESPITE THEIR FRIGHTENING close encounter with the V-2 in London, Arthur Clarke and the other directors of the British Interplanetary Society were optimistically anticipating the coming rocket age. In particular, they wondered if an increased interest in rockets and space might affect their post-war careers or lead to entrepreneurial opportunities. Clarke’s mind turned in this direction when contemplating possiblities for radio and television communication stations in space.

Early in 1945 he wrote a letter to the magazine Wireless World, in which he proposed a novel idea. If three geosynchronous satellites were placed in stationary orbits above fixed points on the globe, each would act like a radio mast erected 22,300 miles above the Earth. Signals sent from a ground station could be received by the satellite in orbit and then amplified and retransmitted over a third of the globe. His letter persuasively argued that a technology ostensibly developed for war could also have peaceful applications far more beneficial to humanity.

During that summer he expanded the idea into a four-page article, “The Future of World Communications,” which, after being cleared by RAF censors and re-titled “Extra-Terrestrial Relays: Can Rocket Stations Give World-Wide Radio Coverage?”, was published in the October issue of Wireless World. Its publication was the first to outline a geosynchronous communications-satellite network and is now considered one of the landmark technical publications of the twentieth century.

Clarke later jokingly noted that his article was met with monumental indifference and earned him a total income of fifteen pounds. But, in fact, it was read in the right places. Copies circulated in offices of the United States Navy and within a newly created private nonprofit called Project RAND, an American think tank designed to coordinate military planning with research and development.

A second, less historically important technical article written by Clarke had far greater immediate personal impact on its author. Shortly before Clarke was demobilized in 1946, “The Rocket and the Future of Warfare” was published in The Royal Air Force Quarterly. He sent a copy to a young Labour MP, who upon reading it said he wanted to meet its author. Coincidentally, their meeting occurred just after Clarke had been deemed ineligible for a university educational grant. In the course of their conversation at the House of Commons, twenty-eight-year-old Clarke told the MP about his predicament. “In a very short time, my grant was approved and I applied for admission to King’s College, London.” Rockets had not taken Clarke into outer space, but they indirectly propelled the farm boy toward a university education.

In addition to their technical publications and books of nonfiction,Tsiolkovsky, Oberth, and Ley had written works of science fiction to popularize their ideas of space travel. A similar impetus prompted Clarke to begin work on a second novel. Between semesters, Clarke set aside his studies in physics and math to write Prelude to Space. It wouldn’t be published for another five years, but it was his first attempt to articulate his optimistic vision of the coming space age.

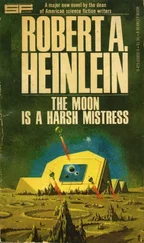

The most commercially successful American work of space advocacy published during the late 1940s was an oversized book written by Willy Ley and illustrated by artist Chesley Bonestell titled, in tribute to David Lasser, The Conquest of Space. While its objective paralleled that of Lasser’s book published nearly two decades earlier, the Viking Press volume found a much larger readership curious to learn the fundamentals of rocket science and the promise of the coming space age. Bonestell’s scientifically accurate astronomical paintings were already familiar to readers of Life magazine and Collier’s, another mass circulation weekly. His work was also known to American moviegoers, though his efforts in Hollywood remained largely unheralded at the time: He had created the architectural renderings of Xanadu in Citizen Kane and the futuristic skyscrapers in the film adaptation of Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead.

For many children growing up in the early 1950s, the imaginary yet scientifically accurate images in The Conquest of Space served as their visual introduction to spaceflight. The book’s success led to public-speaking engagements for Ley, including appearances on the emerging medium of television, where he explained what the recent talk about space travel could mean for the future. In his role as a popular science writer, authority on space, and debunker of pseudoscientific fads and occultist beliefs, Ley served as a voice of avuncular reason amid a flood of sensational UFO reports that appeared frequently in newspapers and magazines during the early Cold War era.

Across the Atlantic, producers at the BBC had similar programming needs. When they wanted someone who could clearly communicate scientific ideas to the general public, Arthur Clarke was the person they repeatedly called upon, and he soon established himself as a minor national TV personality. Now living in North London within walking distance of the BBC’s television broadcast studio, Clarke appeared not only in his role as the spokesperson for the British Interplanetary Society but also as a frequent guest whenever a producer required someone on short notice to speak about astronomy, space science, physics, or even the fourth dimension. These early appearances occurred at roughly the same moment as the publication of Clarke’s first nonfiction book, Interplanetary Flight, a short volume advocating for space exploration.

Читать дальше