Copyright

Copyright

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

HarperCollins Publishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

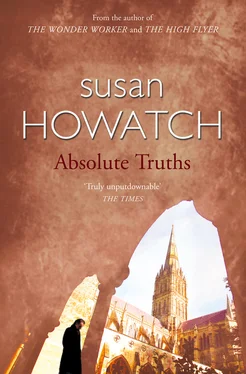

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Publishers 1995

Copyright © Leaftree Ltd 1995

The Author asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollins Publishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780006496885

Ebook Edition © MAY 2012 ISBN: 9780007396375

Version: 2019-01-08

‘A tour de force … Susan Howatch has been likened to a twentieth-century version of Trollope. To make such a comparison is to fail to do her justice’

Church of England. Newspaper

‘Howatch writes thrillers of the heart and mind … everything in a Howatch novel cuts close to the bone and is of vital concern’

New Woman

‘Riveting … extremely moving and often very funny … She is a deft storyteller, and her writing has depth, grace and pace’

Sunday Times

‘She is writing for anyone who can recognise that mysterious gift of the true storyteller’

Daily Telegraph

‘One of the most original novelists writing today’

Cosmopolitan

‘The best female writer in Britain today’

Birmingham Evening Mail

This book is dedicated to all my friends among the clergy of the Anglican Communion (and in particular the Church of England) with thanks for their support and encouragement. My special thanks also goes to Alex Wedderspoon for his great sermon preached in Guildford Cathedral in 1987 on the eighth chapter of St Paul’s Epistle to the Romans, verse twenty-eight.

COVER

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT

PRAISE

DEDICATION

PART ONE: TRADITION AND CERTAINTY

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

PART TWO: CHAOS

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

PART THREE: PARADOX AND AMBIGUITY

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

PART FOUR: REDEMPTION

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

KEEP READING

AUTHOR’S NOTE

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

BY SUSAN HOWATCH

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

PART ONE TRADITION AND CERTAINTY

‘Absolute truth is a very uncomfortable thing when we come into contact with it. For the most part, in daily life, we get along more easily by avoiding it: not by deceit, but by running away …’

REGINALD SOMERSET WARD (1881–1962)

Anglican Priest and Spiritual Director

To Jerusalem

‘No doubt it would be more suitable for a theologian to be absolutely pickled in devout reflection and immune from all external influences; but wrap ourselves round as we may in the cocoon of ecclesiastical cobwebs, we cannot altogether seal ourselves off from the surrounding atmosphere.’

AUSTIN FARRER

Warden of Keble College, Oxford, 1960–1968

Said or Sung

What can be more devastating than a catastrophe which arrives out of the blue?

During the course of my life I have suffered three catastrophes, but the first two can be classified as predictable: my crisis in 1937 was preceded by a period of increasingly erratic behaviour, and my capture by the Germans in 1942 could have been prophesied by any pessimist who knew I had volunteered on the outbreak of war to be an army chaplain. But the disaster of 1965 walloped me without warning.

Ten years have now passed since 1965, but the other day as I embarked on my daily journey through the Deaths Column of The Times , I saw that my old adversary had died and at once I was recalling with great clarity that desperate year in that anarchic decade when he and I had fought our final battle in the shadow of Starbridge Cathedral.

‘AYSGARTH, Norman Neville (“Stephen”),’ I read. ‘Beloved husband of Dido and devoted father of …’ But I failed to read the list of offspring. I felt too bereaved. How strange it is that the further one journeys through life the more likely one becomes to mourn the loss of old enemies almost as much as the loss of old friends! The divisions of the past seem unimportant; we become unified by the shrinking of the future.

‘Oh God!’ said my wife, glancing across the breakfast table and seeing my expression. ‘Who’s died now?’

Having answered her question I turned from the small entry in the Deaths Column to the many inches of unremitting praise on the obituary page. Did I approve of this fulsome enactment of the cliché Nil nisi bonum de mortuis est? Summoning all my Christian charity I told myself I did. I was, after all, a retired bishop of the Church of England and supposed to radiate Christian charity as lavishly as the fountains of Trafalgar Square spout water. However, I did think that the allocation of three half-columns to this former Dean of Starbridge was a trifle generous. Two would have been quite sufficient.

‘What a whitewash!’ commented my wife after she had skimmed through this paean. ‘When I think back to 1965 …’

I thought of 1965, the year of my third catastrophe, the year Aysgarth and I had fought to the finish. Bishops and deans, of course, are not supposed to fight at all. Indeed as senior churchmen they are required to be either holy or perfect English gentlemen or, preferably, both.

How we all hanker after ideals, after certainties – and after absolute truths – which will provide us with security as we struggle to survive in the ambiguous, cloudy, chaotic world which surrounds us! Moreover, although in a rapidly changing society ideals may appear to be swept away by a rising tide of cynicism, the experience of the past demonstrates that people will continue to hunger for those ideals, even when absolute truths are no longer in fashion.

Society was certainly changing with great speed in the 1960s, and when I was a bishop I became famous for defending tradition at a time when all traditions were under attack. I had two heroes: St Augustine, who had proclaimed the absolute truths till the end, even as the barbarians advanced on his city, and St Athanasius, the bishop famous for being so resolutely contra mundum , against the world, as he fought heresy to the last ditch. By 1965 I had decided that I, like my two heroes, was being obliged to endure a dissolute, demoralised, disordered society, and that my duty was to fight tooth and nail against decadence. A fighting bishop unfortunately has little chance to lead a quiet life, but I decided that was the price I had to pay in order to preserve my ideals.

Читать дальше

Copyright

Copyright