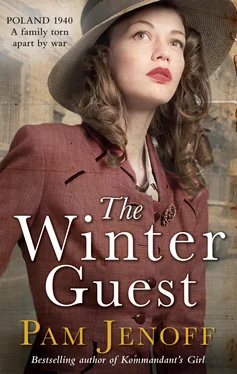

She pulled back the shutter that covered one of the broken windows to allow the pale light to filter in. The soldier was curled up in a tight ball on the ground, much as he had been when she found him, but farther from the door. She hesitated as excitement and alarm rose in her. What was she thinking by coming here? She didn’t know this man, or whether he was here to help or do harm.

Helena walked over and knelt to feel his cheek, caught off guard by the softness of his skin. She was relieved to find he was still warm. Then she remembered Karolina’s illness, barely passed. Had she made a mistake by coming and possibly bringing sickness to this man in his already-weakened state?

The soldier moved suddenly beneath her hand and she jumped. His eyes snapped open. He stiffened, almost as Mama had when she feared pain in the hospital.

“It’s okay,” Helena said, holding her hands low and open. “I’m the one who brought you here.”

He forced himself to a sitting position, trying without success to stifle a whimper. “Who are you?” His Polish was stiff and a bit accented.

“I’m called Helena. I live close to the village. You should rest,” she added.

But he sat even straighter, clenching and unclenching his hands. His chocolate eyes, set just a shade too close together, darted back and forth. “Does anyone else know that I’m here?”

“Not that I’m aware,” she replied quickly. “I haven’t told anyone.” She wanted to say that someone else might have heard the crash, but it seemed unwise to upset him more.

He stared at her, disbelieving. “Are you sure?”

“I haven’t told anyone,” she repeated, suddenly annoyed. “Why would I have gone to all of the trouble to save you just to turn you in?”

He shrugged, somewhat calmer now. “A reward, maybe. Who knows why people do anything these days?”

“No one knows that you’re here,” she replied, her voice soothing.

“Where is ‘here’ exactly?” he asked.

“Southern Poland, Małopolska. You’re about twenty kilometers from the city.”

“Kraków?” Helena nodded, sensing from his expression that her answer was not what he expected. “That puts us about an hour from the southern border, doesn’t it?”

“Roughly, yes. Perhaps a bit more.”

His face relaxed slightly. “You’re real.” She cocked her head. “I thought I might have been delirious and dreamed you. And then I wasn’t sure you were coming back.”

“I’m sorry,” she replied quickly. “It’s hard to get away.” He had rugged features, an uneven nose and a chin that jutted forth defiantly. But his eyelashes were longer than she knew a man could have, and there was a softness to his gaze that kept him from being too intimidating.

“I didn’t mean it that way,” the man added. “Just that I’m glad to see you again.” A warm flush seemed to wash over her then, and she could feel her cheeks color. “I don’t think I introduced myself properly. Sam Rosen.” He held out his hand. “I’m American.” His deep voice had a lyrical quality to it, the words nearly a song.

“But you’re speaking Polish.”

“Yes, my grandparents were from one of those eastern parts by the border that was Poland when it wasn’t Russia. They used to speak Polish with my mother when they didn’t want the children to understand what they were saying. So I had a reason to try to figure it out.” The corners of his mouth rose with amusement.

She shook his outstretched hand awkwardly. He had wiped the blood from his face, she noticed, leaving a narrow gash across his forehead. “You’re looking better,” she remarked, meaning it. There was a ruddiness to his complexion that had not been there before. His hair was darker than she remembered it, almost black. A healed scar ran pale and deep from the right corner of his mouth to his chin.

“Thanks to you,” he replied, his eyes warm. “Bringing me here saved my life. And the food you left did me a world of good.” He made it sound as though she had left him an entire feast and not just a handful of bread.

“A bit more,” she said, passing him another piece of bread, slightly larger. His fingers brushed against her own, coarse and unfamiliar. “I’m sorry that’s all I could manage.” She could not take any of the scarce sheep’s cheese or lard they needed for the children.

“You’re very kind.” His voice was full with gratitude. He tore into the bread with an urgency that suggested true hunger. Of course, the morsel she’d left him last time would not have lasted a day, once he was able to eat. She noticed then a pile of leaves—he must have dragged himself outside to forage. “They taught us in training which things we could eat, roots and such. And I’ve managed to drink some rainwater.” He gestured across the chapel to a puddle that had formed where it had rained through the opening in the roof. “I’m sorry not to get up,” he added. “My leg is still a mess. But I don’t think it needs to be set.”

She looked around the chapel—the wooden pews had rotted to the floor and there was no sign of any pulpit, but fine engravings were still visible on the walls, faded images of angels and the Virgin Mary at the front. “It’s a good thing I found you,” she said, sounding more pleased with herself than she intended. “The path is just off the main road. Someone else might have turned you in to the police for favors or food.”

“What about animals?” he asked. “Are there wolves?”

She hesitated. “Yes.” His eyes widened. She did not want to alarm him, but other than sparing Ruth the occasional bit of reality, it was not in Helena’s nature to lie. Once the wild animals had clung to the high hills, content to feed on small prey. But with food sources growing scarce, they’d become bolder, venturing down to the outskirts of the village to steal livestock.

“Here.” Helena opened her bag. She had looked around the hospital ward while visiting her mother earlier, searching for whatever supplies she could take to help him. There had only been a few rags and a small bottle of alcohol lying on one of the nurse’s carts and she didn’t dare to risk looking in the supply closet or any of the cupboards. She handed the bottle to him. “I brought you these, too.” She pulled out the wool coat and thick gray sweater that had been her father’s. Sam took the sweater and put it on, swimming in its massive girth. She hoped he could not detect the smell of liquor that lingered, even after it had been washed.

“Thank you. My jacket must have been stripped off with the parachute. It’s probably hanging from a tree somewhere.”

So he had fallen from the sky, after all. “So you jumped?”

He nodded. “Before the plane crashed. The weather forced us to fly farther north than we should have, I think, and the pilot had to go off course. At first we received orders to turn back, but we had all agreed that we were too far gone for that—we wanted to see the mission through. Then something went wrong with the plane. We knew we were going to have to wild jump, that means just land anywhere, as well as we could.” She imagined it, leaping from the plane in darkness and mist, not knowing what lay below. “I wasn’t sure my chute was going to have time to open. It did, but I got caught in a tree. When I was trying to free my chute, I fell from the tree and, well...” He gestured to his leg. “The rest you know.”

Sam opened the bottle and doused the cloth, then pressed it against the gash on his forehead, grimacing. He shivered and there was a sudden air of vulnerability about him, as though all of the foreign bits had been stripped away.

“I’ll be right back,” she announced. Before he could respond, Helena rushed outside to the grassy patch above the chapel, collecting an armful of sticks to make a fire. She stopped abruptly. What was she doing coming to the woods to tend to this stranger, risking discovery at any moment? Caretaking had never been in her nature. It was Ruth who nurtured the others, Michal that cared for small, hurt animals. And she had her family’s well-being to think about. She had done enough, too much, her sister would surely say.

Читать дальше

![О Генри - Граф и свадебный гость [Черное платье] [The Count and the Wedding Guest]](/books/405331/o-genri-graf-i-svadebnyj-gost-chernoe-plate-th-thumb.webp)