Part One

1

Individual versus Collective

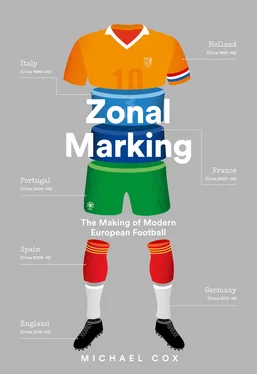

At the start of football’s modern era in the summer of 1992, Europe’s dominant nation was the Netherlands. The European Cup had just been lifted by a Barcelona side led by Johan Cruyff, the epitome of the Dutch school of Total Football, while Ajax had won the European Cup Winners’ Cup. And there was strength in depth domestically – PSV had won the league, Feyenoord won the cup.

Holland failed to retain the European Championship, having won it in 1988, but played exciting, free-flowing fotball at an otherwise disappointingly defensive Euro 92, the last tournament before the back-pass change. Europe’s most dominant player was also a Dutchman – that year’s Ballon d’Or was won by Marco van Basten, while his strike partner at international level, Dennis Bergkamp, finished third.

But the Dutch dominance wasn’t about specific teams or individuals; it was about a particular philosophy, and Dutch sides – or those coached by Dutch managers like Cruyff – promoted this approach so successfully that football’s modern era would be considered in relation to the classic Dutch interpretation of the game.

When Total Football revolutionised the sport during the 1970s, the nature of the approach was widely associated with the nature of Amsterdam. The Dutch capital was the centre of European liberalism, a mecca for hippies from all across the continent, and that was reflected in Dutch football. Ajax and Holland players supposedly had no positional responsibilities, and were seemingly allowed to wander wherever they pleased to create vibrant, free-flowing, beautiful football.

But in reality the Dutch approach was heavily systematised – players interchanged positions exclusively in vertical lines up and down the pitch, and if a defender charged into attack, a midfielder and forward were compelled to drop back and cover. In that respect, while players were theoretically granted freedom to roam, in practice they were constantly thinking about their duties in response to the actions of others. In an era when attackers from other European nations were often granted free roles, Ajax and Holland’s forwards were constrained by managerial guidelines. Arrigo Sacchi, the great AC Milan manager of the late 1980s, explained it concisely: ‘There has only been one real tactical revolution, and it happened when football shifted from an individual to a collective game,’ he declared. ‘It happened with Ajax.’ Since that time, Dutch football has held an ongoing philosophical debate – should football be individualistic like the stereotypical depiction of Dutch culture, or be systematised like the classic Total Football sides?

During the mid-1990s, this debate was epitomised by the rivalry between Johan Cruyff, the golden boy of Total Football now coaching Barcelona, and Ajax manager Louis van Gaal, who enjoyed a more prosaic route to the top. Both promoted the classic Ajax model in terms of ball possession and formation, but whereas Cruyff wholeheartedly believed in indulging superstars, Van Gaal relentlessly emphasised the importance of the collective. ‘Van Gaal works even more structurally than Cruyff did,’ observed their shared mentor Rinus Michels, who had taken charge of those legendary Ajax and Holland sides in the 1970s. ‘There is less room in Van Gaal’s approach for opportunism and changes in positions. On the other hand, build-up play is perfected to the smallest detail.’

The Dutch interpretation of leadership is somewhat complex. The Dutch take pride in their openness and capacity for discussion, which in a footballing context means players sometimes enjoy influence over issues that, elsewhere, would be the responsibility of the coach. For example, Cruyff sensationally left Ajax for Barcelona in 1973 because Ajax employed a system in which the players elected the club captain, and was so offended when voted out that he decamped to the Camp Nou. When you consider Cruyff’s subsequent impact at Barcelona, it was a seismic decision, and one that owed everything to classic Dutch principles.

Dutch players are accustomed to exerting an influence on their manager, and helping to formulate tactical plans. As Van Gaal explained of the Ajax system, ‘We teach players to read the game, we teach them to be like coaches … coaches and players alike, we argue and discuss and above all, communicate. If the opposition’s coach comes up with a good tactic, the players look and find a solution.’ While in many other countries, players instinctively follow the manager’s instructions, a team of Dutch players may offer eleven different opinions on the optimum tactical approach, which partly explains why the national side are renowned for constantly squabbling at tournaments – they’ve always been encouraged to articulate tactical ideas. This inevitably leads to disagreements, and players in the national side only ever seem to agree when they decide to overthrow the coach.

Michels, the father of Total Football, actively encouraged dissent with his so-called ‘conflict model’, which involved him luring players into dressing-room arguments. ‘I sometimes deliberately used a strategy of confrontation,’ he admitted after his retirement. ‘My objective was to create a field of tension, and improve the team spirit.’ Crucially, Michels acknowledges he always picked on ‘key players’, and when a nation’s most celebrated manager admits to provoking his best players into arguments, it’s hardly surprising that those in future generations saw nothing wrong with squabbling.

This emphasis on voicing opinions means Dutch players are often considered arrogant by outsiders, and this is another concept linked to the nature of Amsterdam. The original Total Footballers of the 1970s Ajax team were described by Cruyff as being ‘Amsterdammers by nature’, the type of thing best understood by his compatriots. Ruud Krol, that side’s outstanding defender, outlined it further: ‘We had a way of playing that was very Amsterdam – arrogant, but not really arrogant, the whole way of showing off and putting down the other team, showing we were better than them.’ Dennis Bergkamp, on the other hand, claims it is simply ‘not allowed to be big-headed in the Netherlands’, and describes the notoriously self-confident Cruyff as ‘not arrogant – it’s just a Dutch thing, an Amsterdam thing.’

Van Gaal was arguably even more arrogant than Cruyff, and was so frequently described as ‘pig-headed’ that critics sometimes appeared to be making a physical comparison. Upon Van Gaal’s appointment as Ajax boss he told the board: ‘Congratulations for appointing the best manager in the world,’ while at his first press conference, chairman Ton Harmsen introduced him with the words, ‘Louis is damned arrogant, and we like arrogant people here.’ Van Gaal was another who linked Ajax’s approach to the city. ‘The Ajax model has something to do with our mentality, the arrogance of the capital city, and the discipline of the small Netherlands,’ he said. Everyone in Amsterdam acknowledges their collective arrogance, but no one seems to admit to individual arrogance, which rather underlines the confusion.

His long-time rival, Cruyff, was arrogant for a reason: he was the greatest footballer of the 1970s and the greatest Dutch footballer ever. His career was littered with successes: most notably three Ballons d’Or and three straight European Cups. He also won six league titles with Ajax, then moved to Barcelona and won La Liga, spent some time in the United States before returning to Ajax to win another two league titles. In 1983, when not offered a new contract at Ajax, he took revenge by moving to arch-enemies Feyenoord for one final year, won the league title, was voted Dutch Footballer of the Year, and then announced his retirement. Cruyff did what he pleased and got what he wanted, enjoying all this incredible success while simultaneously claiming that success was less important than style. He personified Total Football, which made his status – as the only true individual in an otherwise very collective team – somewhat curious. He was a popular choice as Ajax manager in 1985, just a year after his playing retirement. He won the Cup Winners’ Cup in 1987 and inevitably headed to another hero’s welcome in Barcelona, where he won the Cup Winners’ Cup again in 1989, then Barca’s first-ever European Cup in 1992 and their first-ever run of four straight league titles. A legendary player had become a legendary coach.

Читать дальше