Noëlle was boarding en famille in a travelling cabal held together by affection, vaguely complementing itineraries and curiosity about the Titanic . Her companion as far as New York was her husband’s cousin Gladys, a vivacious and unmarried fixture of the London social scene who had decided to keep Noëlle company for the voyage and visit her brother, Charles Cherry, an aspiring theatre actor who had moved to New York two years earlier. Gladys and Noëlle were friends and, following the convention of most families at the time, referred to each other as ‘my cousin’ after Noëlle and Norman’s marriage. They were joined by Noëlle’s parents, Thomas and Clementina Dyer-Edwardes. Thomas had taken long voyages before – indeed, arguably one of the longest possible when he had sailed from England to Australia in the 1860s to spend ten years increasing the family’s fortune – but this trip on the Titanic was not to add to the roster of his far-flung travels. He and Clementina were only going as far as the Titanic ’s first port of call, the town of Cherbourg in north-western France. From there, they would travel to Château de Rétival, their eighteenth-century house in Normandy, which they were opening up for the summer. Since they usually made the first annual trip to expel Rétival’s dust covers in spring, the Dyer-Edwardeses had decided to combine their cross-Channel trip with Noëlle’s departure for America. It would be a chance to wish their only child Godspeed before she was gone for several months, with the added attraction of travelling, however briefly, on the inaugural voyage of the world’s largest liner. There seems to have been a slight delay with the boat train from Waterloo, which did not reach Southampton until about 11.30, thirty minutes before the ship’s scheduled departure.[26]

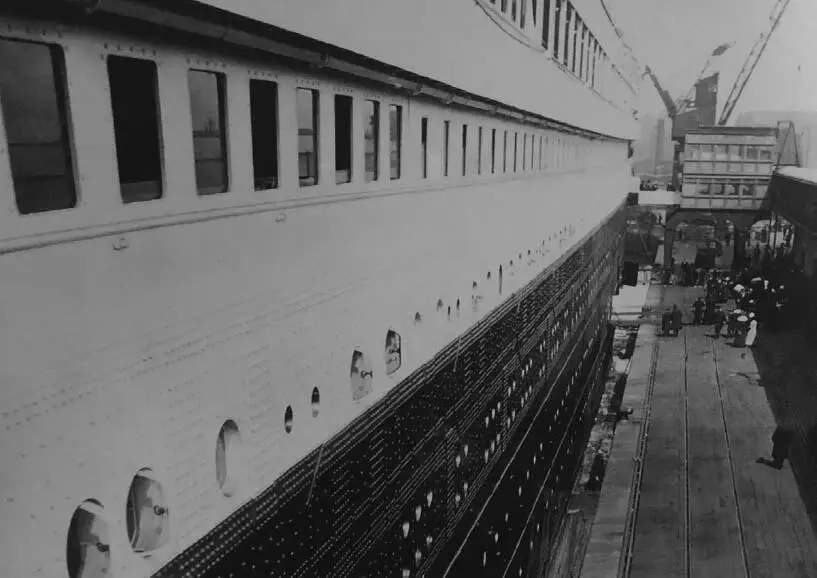

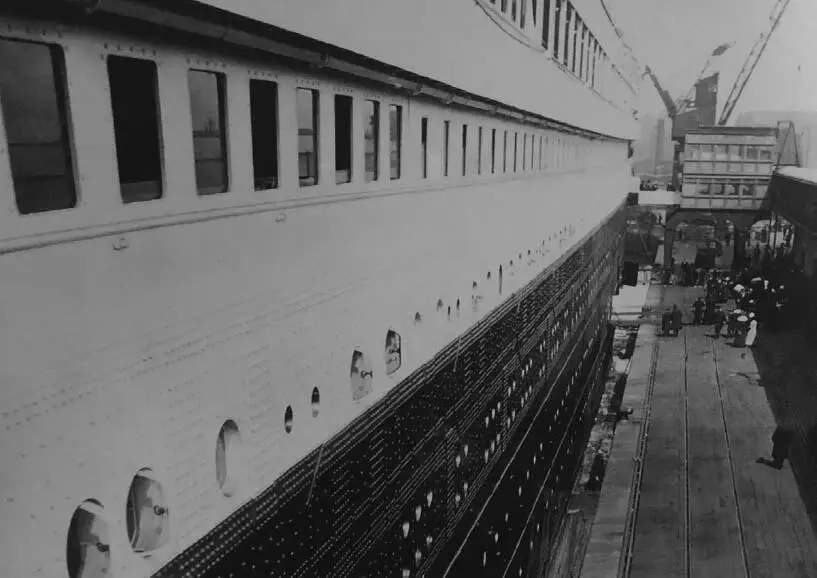

When the train came to a halt on tracks running parallel to the Titanic ’s towering hull, the Countess’s party stepped out into a large shed, nearly 700 feet in length, where a small industrious army of porters were dealing with the last of the ship’s cargo and luggage.[27] Noëlle’s steamer trunks were added to their task as she, her parents, Gladys and Noëlle’s lady’s maid, Cissy Maioni, crossed under the skylights and up the stairs to an enclosed balcony, where they presented their tickets.[28] They were ushered over the 28 feet of the gangplank from which, turning right, they could see the second-class walkway, on the same level but 500 or so feet aft, and one of the third-class gangways, three decks below.

The view from the first-class gangplank on departure day. Those used by Second (above) and Third Class (below) can be seen in the distance.

View from the first-class gangplank of the RMS Titanic at approximately 11.30 a.m. on Wednesday 10 April 1912, as photographed by passenger, Father Francis Browne, SJ (Science & Society Library/Father Browne Collection)

They arrived to see crew members waiting for them in a white-panelled vestibule with a black-and-white-patterned floor, which had such a gleaming finish that some passengers initially mistook it for marble.[29] Several of the Titanic ’s officers were required to be on meet-and-greet duty for the first-class passengers, a piece of etiquette that had survived in transmogrified form from the days of sail when the owners of ships had often escorted prominent passengers on board themselves.[30] However, it was the stewards and stewardesses, not the officers, who offered practical help by escorting the passengers to their rooms. Since they were only going as far as France, Noëlle’s parents had a ticket which entitled them to lunch and afternoon tea, but no cabin. Noëlle herself and Gladys were to spend six or seven nights as roommates in cabin C-37.[31]

The Titanic ’s decks were labelled with alphabetical efficiency. Unlike many other liners, where decks were often given a name indicating their purpose, like ‘Shelter’, ‘Saloon’ or ‘Upper’, the Titanic ’s top deck, which was open to the elements and housed her lifeboats, was called the ‘Boat Deck’, but after that her levels were ranked in consecutive descent from A- through to G-Deck, the final point accessible to passengers, below which were the boiler and engine rooms.[32] A common misconception about the allocation of space for the respective traveller classes was that the liners’ architecture directly replicated the concept of social hierarchy, with First Class occupying the top decks and Third spread over the lowest. In reality, the most stable parts of a liner are amidships, since they are the least prone to pitching during inclement weather. On Titanic , First and Second Class were located amidships, running downward through the ship and linked for the crew by various corridors. Both classes had access to the air on the Boat Deck, with a low dividing rail separating Second Class’s aft promenade from First’s more expansive, forward-facing space. First-class cabins, generally referred to by the slightly grander adjective of ‘stateroom’, ran from A- to E-Deck, while the public rooms were dotted around from the Gymnasium, through a door off the Boat Deck, to the Swimming Pool, Racquet Court and Turkish Baths down on F-Deck. Their public rooms generally lay on either side of the two sets of staircases, one forward and one aft, running through every level of first-class accommodation. The space between the staircases was connected by the stateroom corridors.

Every passenger with a first-class ticket had access to the same amenities and food included in the tariff, but there were significant gradations of luxury and corresponding cost when it came to the staterooms. The most expensive single class of ticket on the Titanic , one of the two suites with their own private verandahs, were located on B-Deck, and it was on B- and C-Deck that the ship’s most lavish accommodation was located. The only noticeable difference between the two decks’ staterooms was their windows – B-Deck was the lowest level of the Titanic ’s white-painted superstructure, enabling her cabins and suites to offer rectangular windows. Immediately below and also painted white, C-Deck was the highest deck in the Titanic ’s otherwise black hull; all cabin windows in the hull were the more traditional nautical portholes.

At Southampton, the Countess of Rothes and the other first-class travellers boarded straight on to B-Deck and, having confirmed their cabin numbers, were escorted by stewards from the vestibule, immediately turning right. They would then either have walked down the stairs or, less probably given how short the distance was, taken one of the three lifts to C-Deck. It was possible for first-class passengers travelling with their own servants, as Noëlle was with Cissy Maioni, to book them into cabins in Second Class, but Noëlle had evidently decided that that was rather mean-spirited, with the result that Cissy was to occupy a first-class cabin of her own, two levels below, on E-Deck.[33]

Between the train and the gangplank, the Countess had been asked for a comment by the English correspondent of a foreign gossip column, who wanted to know what the doyenne of the beau monde felt about ‘leaving London Society for a California fruit farm’. With her imperturbable no-nonsense cheer, the Countess had smiled back, ‘I am full of joyful expectation.’[34] Unfortunately, joyful expectation experienced its first stutter when the door to C-37 was opened for them. The Titanic ’s surviving deck plans give several possible reasons for Noëlle’s request to be moved – the first being C-37’s location so close to the stairwell and lifts. It was located in the corridor immediately leading off from them, which may have made Noëlle worry unnecessarily about possible noise and disturbance. There was also the issue of C-37’s size, which offered comfortable if standard first-class accommodation, different to the more splendid options profiled in the White Star Line’s advertising.[35] It has been suggested that Lady Rothes’ parents decided to treat their daughter and her companion to an upgrade; it has also been suggested that the room was unsuitable for the Countess. The two explanations are not wholly contradictory. The Purser’s Office was on the same deck and requests to be moved were not uncommon. An admiring captain with the Cunard Line thought that pursers and their staff on board the great liners ‘do most of the clerical work of this floating city; the purser’s office is a kind of “enquire within” bureau for passengers; it is a reception office; it is the place where complaints are ventilated, and where official oil is poured on the sometimes troubled waters that are bound to occur in a ship that carries, as she often does, thirty different nationalities – including people of widely different tastes, customs, temperaments and requirements’.[36] Upon hearing that the request for a new room concerned Lady Rothes, Purser McElroy seems to have moved with breakneck speed.

Читать дальше