No one was listening. It was a man of action who flourished in April 1912, drowning out men of prudence. Unionism was now dominated by leaders like the lawyer Edward Carson, who had once served as the prosecuting counsel against Oscar Wilde, and the Andrewses’ family friend, the ferociously uncompromising Sir James Craig. To make explicit how far they were prepared to go if Home Rule was extended to Ulster, the Ulster Volunteer Force, the Orange Order and the heads of the north’s major industries were organising one of the largest mobilisations of political sentiment in Irish history, a covenant due to be paraded through the province to an enormous final rally outside Belfast City Hall.[66] Agents were sent out to help those in the smaller towns and countryside who wanted to sign. Tommy Andrews and the men in his family intended to sign this declaration:

being convinced in our consciences that Home Rule would be disastrous to the material well-being of Ulster as well as of the whole of Ireland, subversive to our civil and religious freedom, destructive of our citizenship, and perilous to the unity of the Empire, we, whose names are underwritten, men of Ulster, loyal subjects of His Gracious Majesty King George V., humbly relying on God whom our fathers in days of stress and trial confidently trusted, do hereby pledge ourselves in solemn Covenant, throughout this our time of threatened calamity, to stand by one another in defending, for ourselves and our children, our cherished position of equal citizenship in the United Kingdom, and in using all means which may be found necessary to defeat the present conspiracy to set up a Home Rule Parliament in Ireland. And in the event of such a Parliament being forced upon us, we further solemnly and mutually pledge ourselves to refuse to recognise its authority. In sure confidence that God will defend the right …[67]

Partly from despair and frustration that unionism would never willingly give so much as an inch in compromise and partly in tune with the mounting radicalisation of nationalist politics across Europe, Irish nationalism was evolving and splitting into republicanism, itself increasingly shaped by die-hards like Pádraig Pearse. Moderation had become a tarnished virtue, a tired or even pathetic concept. Although he begged his followers to ‘restrain the hotheads’, Edward Carson simultaneously urged them to ‘prepare for the worst and hope for the best. For God and Ulster! God Save the King!’[68] On the other side of the soon actualised barricades, Pearse urged his followers to hope for civil war, to pray for rebellion and for all of British Ireland to vanish in flames regardless of the human cost, because ‘Blood is a cleansing and sanctifying thing, and the nation that regards it as the final horror has lost its manhood.’[69] From their respective demagogues, all sides in Ireland heard the sibyl cry of their pasts, promising them the future glory of a war without ambiguity. Protestant and Catholic, loyalist and nationalist, Ireland would willingly wrestle itself off a cliff edge, plunging the entire island into the unknown. The head of the police service, the Royal Irish Constabulary, told the Chief Secretary of Ireland, ‘I am convinced that there will be serious loss of life and wholesale destruction of property in Belfast on the passing of the Home Rule bill.’[70]

When he arrived back in Belfast that night, after the sea trials, Andrews sent a note to his wife in Malone. Everything had gone well; there were one or two problems, which would no doubt be fixed by the time the ship reached Southampton three days later. Francis Carruthers had been duly satisfied by Titanic ’s performance and he had granted her the Board of Trade’s standard twelve-month certificate as a passenger ship.[71] Andrews and Wilding spent the night on board, to prepare for the early-morning departure to England. The Union Jack fluttered from one of the Titanic ’s flagpoles as the sun set around the slumbering leviathan with the fire burning unchecked within her interiors.

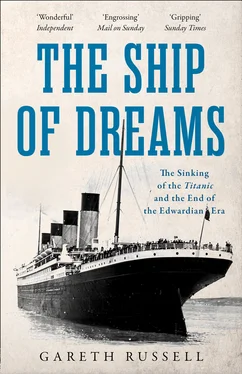

[The Titanic ] was so much larger than one even expected; she looked so solidly constructed, as one knew she must be, and her interior arrangements and appointments were so palatial that one forgot now and then that she was a ship at all. She seemed to be a spacious regal home of princes.

Ernest Townley, interview given to the Daily Express (16 April 1912)

ONE WEEK AFTER HER MIDNIGHT ARRIVAL ATSouthampton, the Titanic ’s main mast ran the company’s red flag with its eponymous white star, fluttering over final preparations for her first commercial voyage.[1] The day of departure, Wednesday 10 April, was overcast in the south of England, with the sun occasionally appearing from behind the scudding clouds to provide a mild temperature of about 9 degrees centigrade as the crew, numbering about 900, were divided into three groups for the muster. Firemen, seamen and those assigned to care for the soon-to-board passengers went through their final medical checks and a head count, carried out under the watchful eye of another representative of the Board of Trade, who then proceeded to observe as two of the ship’s twenty lifeboats were lowered down the side with eight trained crew wearing their lifejackets. Typically, this inspection would involve the tested lifeboats unfurling their sails, but an uncooperative breeze put pay to that, so the white-painted wooden craft were successfully raised back on to deck and into their davits, with their virgin sails left unfurled. Vast quantities of luggage were being manoeuvred on board. Pieces bound for the first-class quarters bore White Star-provided labels with variants of ‘CABIN’ or ‘STATEROOM’, to indicate that they should be taken to the passenger’s bedroom; ‘BAGGAGE ROOM’ or ‘WANTED’, if they were not to go immediately to their accommodation but contained items which might be required later in the voyage, a helpful utilisation of space given the upper classes’ minimum requirement of three outfit changes daily; and ‘NOT WANTED’, if the pieces were to go into the hold until disembarking.[2]

Thomas Andrews had arrived on board half an hour or so after dawn that morning, checking out from his interim accommodation at the nearby South-Western Hotel, where he had stayed in the week since leaving Belfast.[3] The days in between had been spent overseeing the last touches to the Titanic ’s accommodation, which produced the kind of productive mania at which Andrews excelled. The ship’s schedule had already been altered, and then squeezed, by her elder sister’s accident in the Southampton waters a few months earlier when, moments after departure, the Olympic had collided with the British warship Hawke .[4] Mercifully, there had been no serious injuries, but a trip to Belfast for repairs was required, with the result that construction on the Titanic temporarily halted for a few days, tightening the preparation time allowed for the maiden voyage. Andrews himself did not doubt that ‘the ship will clean up all right before sailing on Wednesday’, but with the door hinges and paint still being applied to the Titanic ’s Parisian-style café on Wednesday morning, White Star had ordered in vast quantities of fresh flowers which went straight into Titanic ’s cold storage to be brought out over the course of the voyage to disguise any lingering smell of varnish.[5] Fixtures in some of the second-class lavatories needed to be attached, furniture bought from firms in England had to be delivered, the furniture in the Café Parisian still was not the right shade of green, and the pebbledashing in two of First Class’s most expensive private suites was too dark.[6] Andrews had overseen everything he could. His secretary, Thompson Hamilton, who had joined him from Belfast for the week, noticed, ‘He would himself put in their place such things as racks, tables, chairs, berth ladders, electric fans, saying that except he saw everything right he could not be satisfied.’[7] Meanwhile, a hose was working away on the contained fire in one of Boiler Room 5’s coal bunkers, with the source expected to be extinguished in the next few days.[8] By the evening of the 9th, everything of note had apparently been taken care of and Andrews could write to his wife, ‘The Titanic is now about complete and will I think do the old Firm credit to-morrow when we sail.’[9]

Читать дальше