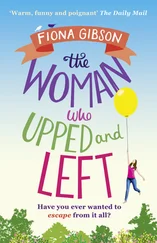

For a few years I worked from a desk in our bedroom. I am a freelance illustrator, and had accumulated a small roster of clients before the twins came along. During my early years of motherhood, I’d tackle any commissions after the kids had gone to bed. I also did some occasional life modelling – i.e. with my clothes off – for local art classes, to bring in extra cash. In a weird sort of way, they offered a bit of respite from family life. Reclining nakedly on a sofa was pretty soothing compared to chipping hardened Weetabix off the floorboards – and I assumed the kids would never find out what it really involved. Anyway, I was around so much after nursery and school that Alfie and Molly didn’t actually believe I worked at all. Their primary school teacher laughingly told me that, when she’d asked Molly what her mum did for a living, she’d replied, ‘She colours in.’

In contrast, Danny did go to work – not in a nine-to-five sense, but for weeks at a time if he was away filming, or to his study at home where he’d hide away to work on edits or scripts.

‘Nadia, the kids keep coming in!’ he’d yell.

‘They just need to see you for a minute, Danny. Alfie wants to show you something he made at school …’

‘Honey, please. Can’t you just keep them at bay?’ he’d say, as if they weren’t his six-year-old children, but wild bears. But then, Danny’s work was all-consuming, and it was my job to thwart the kids’ access to He Who Must Not Be Disturbed.

‘Daddy’s busy being Steven Spielberg,’ I’d explain, ushering them away.

‘Who’s Steven Spee—’ Alfie would start.

‘A very important film man like Dad,’ I’d say. Alfie always needed more reassurance than Molly, and I was conscious of over-compensating for Danny’s unavailability: painting with the kids whenever they demanded it, and indulging Alfie’s lengthy baking craze. The more cakes he made, the more I felt obliged to scoff (‘Sounds like a feeble excuse to me,’ Danny had sniggered), my once-slender body expanding and softening, my skimpy knickers making way for sturdy mummy-pants.

Meanwhile, Danny remained his gangly, raffishly handsome self, all messy dark hair and stubble. He seemed to experience no guilt whatsoever on turning down one of Alfie’s Krispie cakes: ‘They look great, Alf, but I’m not really into that breakfast-cereal-confectionery hybrid.’ He didn’t intend to be mean, and the kids still adored him. However, Danny had always done whatever he wanted and he didn’t really worry what anyone else thought.

I’d known, when I got together with a film-maker, that I might be signing up for an unconventional sort of life. However, I also knew that other film-makers – friends of Danny’s – managed to be reasonably functioning adults, able to maintain healthy, happy relationships. To my knowledge they never left their partners stranded in restaurants because they’d gone to a lecture on Hitchcock and the Art of Cinematic Tension instead (on aforementioned partner’s fortieth birthday). Nor had they blown a small inheritance from an uncle by drunkenly bidding on one of the actual suits worn in Reservoir Dogs . Of course it wasn’t just about the suit or the missed meals; it was loads of stuff, piled up year after year.

Although it was me who finally decided we should split – Danny and I had never married – he didn’t exactly beg me to reconsider. I think we both knew we’d reached the end of the line. And so he moved out, to a rented flat half a mile away, and we both did our best to present our break-up in a non-dramatic manner. ‘We’re still friends who care about each other,’ I told Molly and Alfie – which was actually true.

A year or so later, Danny started seeing a make-up artist ten years his junior. I was fine with that, truly; Danny and I were managing to get along pretty cordially, and I was enjoying teasing him about his new liaison. ‘So how are things with Kiki Badger?’ I asked during one of our regular chats on the phone.

I heard him exhale. ‘Nads, why d’you always do this?’

‘Do what?’

‘You know. Use both of her names.’

I smirked. ‘It’s one of those names you have to say in full …’

‘Why?’

‘Because it sounds like a sex toy. “The batteries in my Kiki Badger have gone flat!”’

‘You’re ridiculous,’ he exclaimed, laughing. Then, after a pause: ‘It’s nothing serious, y’know? We’re just … hanging out.’ Yeah, sure. ‘How about you?’ he asked. ‘Is there anyone …’

‘You know there isn’t,’ I said quickly.

‘No I don’t. You might have someone squirrelled away—’

‘Hidden in a cupboard?’

‘Maybe,’ he sniggered.

‘Chance’d be a fine thing,’ I retorted, but in truth I wasn’t too interested. It’s not that Alfie and Molly would have kicked off if I’d started seeing someone; at least, I don’t think they would have.

As it turned out, their dad and Kiki have stuck together over the years, and the kids have always seemed fine with that. However, they lived with me, and perhaps that made me more cautious. I wasn’t prepared to endure some teeth-gritting, ‘Alfie, Molly – this is Colin!’ kind of scenario at breakfast with some bloke I wasn’t particularly serious about. There were a couple of brief flings, conducted when Molly and Alfie were at their dad’s, and a significant one, eighteen months ago; well, it was significant to me. But since then? Precisely nothing.

It’s fine, honestly. It really is. It’s just slightly galling that the kids have left home and I’m free as a bird – yet I’ve found precisely no one to tempt into my nest.

And yet … celibacy has its advantages. It really does!

I’m not even saying that in a bitter tone, with my teeth gritted. I can happily wander about with hairy bison legs beneath my jeans, if I want to. I can orgasm perfectly well by myself, and have plenty of friends to knock around with. Corinne and Gus are two of my closest; we’ve all known each other since our art college days in Dundee, and these days we share a studio pretty close to the city centre. As my children grew up, and I managed to establish myself properly, I reached the point where I could finally afford to work outside of the flat. It feels like a luxury sometimes, as now Alfie and Molly have left I can hardly complain about the lack of space at home. But I love working here. Our studio is the top floor of a tatty old warehouse, currently decked out with decorations and a sparkling white tree, as Christmas is approaching.

‘So your present to yourself is to get online,’ remarks Gus, as he makes coffee for the three of us.

‘I’m not joining a dating site,’ I say firmly.

‘Why not just give it a go?’ He glances over from the huge canvas he’s working on.

‘I’ve told you, Gus. It’s just not my thing.’

I turn back to the preliminary sketches that are littered all over my desk. I’m illustrating a series of study guides covering English, maths and history, and possibly more subjects, if the client is happy with the results. As I start to sketch, I’m aware of Gus and Corinne exchanging a look; both of them reckon I have been single for far too long.

It’s a year and a half since I last slept with someone, and that person happened to be Ryan Tibbles, who was also at art college with us, although I hadn’t known him very well when we were students. I’d just experienced a little frisson whenever I glimpsed him mooching around, with his mop of black, shaggy hair and languid expression, a smouldering roll-up permanently clamped between his sexy lips.

After we’d graduated, everyone had scattered all over the country in pursuit of work or to further their studies. I returned to Glasgow, to do admin for a small design company, hoping it would lead to greater things. Ryan, who’d been the star of his year, whizzed off to do a post-grad at St Martins in London. I heard nothing from him for all those years until he turned up out of the blue at a party at Corinne’s.

Читать дальше