Neil Gaiman’s dark-fantasy novella Coraline bears Gorey’s stamp, too. A devout fan since childhood, when he fell for Gorey’s illustrations in The Shrinking of Treehorn by Florence Parry Heide, Gaiman has an original Gorey hanging on his bedroom wall, a drawing of “children gathered around a sick bed.” 2Gaiman’s wife, the dark-cabaret singer Amanda Palmer, references Gorey’s book The Doubtful Guest in her song “Girl Anachronism”: “I don’t necessarily believe there is a cure for this / So I might join your century but only as a doubtful guest.” 3

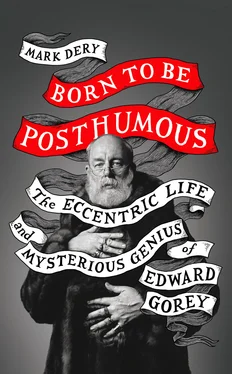

His influence is percolating out of the goth, neo-Victorian, and dark-fantasy subcultures into pop culture at large. The market for Gorey books, calendars, and gift cards is insatiable, buoying indie publishers like Pomegranate, which is resurrecting his out-of-print titles. Since his death, his work has inspired a half dozen ballets, an avant-garde jazz album, and a loosely biographical play, Gorey: The Secret Lives of Edward Gorey (2016). Of course, there’s no surer sign that you’ve arrived than a Simpsons homage. Narrated in verse, in a toffee-nosed English accent, and rendered in Gorey’s gloomy palette and spidery line, the goofy-creepy playlet “A Simpsons ‘Show’s Too Short’ Story” (2012) indicates just how deeply his work has seeped into the pop unconscious.

But the leading indicator of Gorey’s influence is his transformation into an adjective. Among critics and trend-story reporters, “Goreyesque” has become shorthand for a postmodern twist on the gothic—anything that shakes it up with a shot of black comedy, a jigger of irony, and a dash of high camp to produce something droll, disquieting, and morbidly funny.

But is that all we’re talking about when we talk about Gorey? An aesthetic? A style? The way we wear our bowler hats?

Truth to tell, we hardly know him.

Gorey’s work offers an amusingly ironic, fatalistic way of viewing the human comedy as well as a code for signaling a conscientious objection to the present. Handler attributes Gorey’s enduring appeal to the sophisticated understatement and wit of his hand-cranked world, dark though it may be—a sensibility that stands in sharp contrast to the Trumpian vulgarity of our times. The Gorey “worldview—that a well-timed scathing remark might shame an uncouth person into acting better—seems worthy to me,” says Handler.

Like Handler, the steampunks and goths with Gorey tattoos who flock to the annual Edwardian Ball, “an elegant and whimsical celebration” inspired by Gorey’s work, dream of stepping into the gaslit, sepia-toned world of his stories. 4Justin Katz, who cofounded the Ball, believes revelers, many of whom come dressed in Victorian or Edwardian attire, are drawn by the promise of escape from our “Age of Anxiety,” a “chaotic time” of “accelerated media” that is “stressful and rootless” for many.

Gorey, it should be noted, groaned at being typecast as the granddaddy of the goths and would have shrunk from the embrace of neo-Victorians. “I hate being characterized,” he said. “I don’t like to read about the ‘Gorey details’ and that kind of thing.” 5There was more—much more—to the man than charming anachronisms and morbid obsessions.

Only now are art critics, scholars of children’s literature, historians of book-cover design and commercial illustration, and chroniclers of the gay experience in postwar America waking up to the fact that Gorey is a critically neglected genius. His consummately original vision—expressed in virtuosic illustrations and poetic texts but articulated with equal verve in book-jacket design, verse plays, puppet shows, and costumes and sets for ballets and Broadway productions—has earned him a place in the history of American art and letters.

Gorey was a seminal figure in the postwar revolution in children’s literature that reshaped American ideas about children and childhood. Author-illustrators such as Maurice Sendak, Tomi Ungerer, and Shel Silverstein spearheaded the movement away from the bland Fun with Dick and Jane fare of the Wonder Bread ’50s toward a more authentic representation of the hopes, anxieties, terrors, and wonders of childhood—childhood as children live it, not as the angelic age of innocence adults imagine it to be, a sentimental chromo handed down from the Victorians. Gorey was never a mass-market children’s author for the simple reason that publishers, despite his urgings, refused to market his books to children. They were squeamish about the darkness of his subject matter, not to mention the absence of anything resembling a moral in his absurdist parables.

Nonetheless, the Wednesday and Pugsley Addamses of America did read Gorey. In a nice twist, Boomer and Gen-X fans raised their children on The Gashlycrumb Tinies , turning a mock-moralistic ABC that plays the deaths of little innocents for laughs (“A is for Amy who fell down the stairs / B is for Basil assaulted by bears …”) into a bona fide children’s book. Some of those kids grew up to be cultural shakers and movers. The graphic novelist Alison Bechdel, whose scarifying tales of her childhood earned her a MacArthur “genius grant,” is a careful student of Gorey’s “illustrated masterpieces,” as she calls them; the Gorey anthology Amphigorey is among her ten favorite books. 6Following Gorey’s lead, she and others have turned traditionally juvenile genres—the comic book, the stop-motion animated movie, the young-adult novel—to adult ends, opening the door to a new honesty about the moral complexity of childhood. Bechdel’s graphic memoir Fun Home , an unflinching exploration of growing up lesbian in the shadow of her abusive father, is only one of a host of examples.

The contemporary turn toward an aesthetic, in children’s and YA media, that is darker, more ironic, and self-consciously metatextual (that is, aware of, and often parodying, genre conventions and retro styles) would be unthinkable without Gorey. Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children (2011), a bestselling YA novel by Ransom Riggs, is typical of the genre. Unsurprisingly, it was inspired by the “Edward Gorey–like Victorian weirdness” of the antique photos Riggs collected, “haunting images of peculiar children.” 7He told the Los Angeles Times , “I was thinking maybe they could be a book, like The Gashlycrumb Tinies . Rhyming couplets about kids who had drowned. That kind of thing.” 8

Gorey’s art—and highly aestheticized persona—foreshadowed some of the most influential trends of his time. His work as a cover designer and illustrator for Anchor Books in the 1950s put him at the forefront of the paperback revolution, a shift in American reading habits that, along with TV, rock ’n’ roll, the transistor radio, and the movies, helped midwife postwar pop culture. Before the Beats, before the hippies, before the Williamsburg hipster with his vest and man bun, Gorey was part of a charmed circle of gay literati at Harvard that included the poets Frank O’Hara and John Ashbery; O’Hara’s biographer calls Gorey’s college clique “an early and elitist” premonition of countercultures to come, at a time—the late ’40s—when there was no counterculture beyond the gay demimonde. 9Though he’d shudder to hear it, Gorey was the original hipster, a truism underscored by the uncannily Goreyesque bohemians swanning around Brooklyn today in their Edwardian beards and close-cropped hairstyles—the very look Gorey sported in the ’50s.

Before retro took up permanent residence in our cultural consciousness; before the embrace, in the ’80s, of irony as a way of viewing the world; before postmodernism made it safe to like high and low culture (and to borrow, as an artist, from both); before the blurring of the distinction between kids’ media and adult media; before the mainstreaming of the gay sensibility (in the pre-Stonewall sense of a Wildean wit crossed with a tendency to treat life as art), Gorey led the way, not only in his art but in his life as well.

Читать дальше